Four stages of learning theory - unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence matrix - and other theories and models for learning and change

Here is a summary of the explanation, definitions and usage of the 'conscious competence' learning theory, including the 'conscious competence matrix' model, its extension/development, and origins/history of the 'conscious competence' theory.

Related to the 'conscious competence' model also below are other theories and models for personal learning and change.

The earliest origins and various definitions of the 'conscious competence' learning theory are uncertain and could be very old indeed; perhaps thousands of years.

Several claims of original authorship exist for the 'conscious competence' model's specific terminology, definitions, structure, etc., as we recognize it today. The most notable claims are as follows, among which the evidence showing Martin M Broadwell as originator seems to be the earliest.

- For many years the US organization Gordon Training International has claimed a major role in defining the theory and and promoting its use since the 1970s.

- Separately, a 1974 technical personnel paper, 'Conscious Competency - The Mark of a Competent Instructor', effectively asserts creation/definition of the concept and basic ('conscious competence') terminology by its author, W Lewis Robinson, an industrial training executive.

- And in August 2013 I was informed (thanks Earl L Wiese, Jr) of an earlier description of the modern-day 'conscious competence' model, featured in the 'Teaching for Learning' article by Martin M Broadwell, dated 20 February 1969, in The Gospel Guardian, an American Christian periodical published from the 1950s-1970s.

These claims, with discussion of other influential/contributing/promotional origins of the 'conscious competence' theory and its modern definitions are shown below, see conscious competence model origins.

The conscious competence theory and related matrix model explain the process and stages of learning a new skill (or behaviour, ability, technique, etc.)

The concept is most commonly known as the 'conscious competence learning model', or 'conscious competence learning theory'; sometimes 'conscious competence ladder' or 'conscious competence matrix'. Other descriptions are used, including terminology relating to 'conscious skilled' and 'conscious unskilled' (which incidentally are preferred by Gordon Training).

Occasionally in more recent adapted versions a fifth stage or level is added to the conscious competence theory, although there is no single definitive five-stage model, despite there being plenty of very useful and valid debate about what the fifth stage might be.

Whether four or five or more stages, and whatever people choose to call it, the 'conscious competence' model remains essentially a very simple and helpful explanation of how we learn, and also serves as a useful reminder of the need to train people in stages.

Stages

Put simply:

Learners or trainees tend to begin at stage 1 - 'unconscious incompetence'.

They pass through stage 2 - 'conscious incompetence', then through stage 3 - 'conscious competence'.

And ideally end at stage 4 - 'unconscious competence'.

Perhaps the simplest illustration of importance of appreciating the need for staged learning is that teachers and trainers can wrongly assume trainees to be at stage 2, and focus effort towards achieving stage 3, when often trainees are still at stage 1. Here the trainer assumes the trainee is aware of the skill existence, nature, relevance, deficiency, and that there will be a benefit from acquiring the new skill. Whereas trainees at stage 1 - unconscious incompetence - have none of these things in place, and will not be able to address achieving conscious competence until they've become consciously and fully aware of their own incompetence. This is a fundamental reason for the failure of a lot of training and teaching.

If the awareness of skill and deficiency is low or non-existent - ie., the learner is at the unconscious incompetence stage - the trainee or learner will simply not see the need for learning. It's essential to establish awareness of a weakness or training need (conscious incompetence) prior to attempting to impart or arrange training or skills necessary to move trainees from stage 2 to 3. People only respond to training when they are aware of their own need for it, and the personal benefit they will derive from achieving it.

Learning Matrix

Here is explanation of how learners/trainees pass from stage to stage in the conscious competence model, and definitions and meanings of each of the stages.

The progression is from quadrant 1 through 2 and 3 to 4. It is not possible to jump stages. For some skills, especially advanced ones, people can regress to previous stages, particularly from 4 to 3, or from 3 to 2, if they fail to practise and exercise their new skills. A person regressing from 4, back through 3, to 2, will need to develop again through 3 to achieve stage 4 - unconscious competence again.

For certain skills in certain roles stage 3 (conscious competence) is perfectly adequate, and in some cases for the reasons which follow, may actually be desirable.

It can be argued that learners who become skilled at level 4 - unconscious competence - cease to be learners. In one respect this is a statement of the obvious, but a more subtle appreciation of this status is that people at this stage can be vulnerable to complacency, by which learning ceases and 'unconscious competence' may in time become an ignorance of or blindness to new methods, technologies, etc., and the expert finds himself once again unconsciously incompetent. There are excellent and revealing parallels here with John Fisher's Process of Personal Transition.

This aspect of 'fourth stage vulnerability' - the implication that stage 4 (unconcious competence) may become complacency or ignorance of new methods - has in part prompted suggestions (by various people since the model first emerged popularly) to extend the 'conscious competence' model to a fifth stage, and understanding these ideas for a fifth stage stage is certainly helpful in addressing compacency and other weaknesses/opportunities relating to continuing development.

Interestingly, progression from stage to stage is often accompanied by a feeling of awakening - 'the penny drops' - things 'click' into place for the learner - the person feels like he/she has made a big step forward, which of course they have. Very clear and simple examples of this effect are seen when a person learns to drive a car: the progression from stage 2 (conscious incompetence) to stage 3 (conscious competence) is obvious, as the learner becomes able to control the vehicle and signalling at the same time; and the next progression from 3 to 4 (unconscious competence) is equally clear to learner when he/she is able to hold a conversation while performing a complex manoeuvre (usually some while after passing the driving test..).

There are other representations of the conscious competence model besides a 2x2 matrix. Ladders and staircase diagrams are popular, which partly stem from the Gordon Training organization's interpretations. The principles remain the same though - it's a simple model and regardless of the varying formats and terminology it is always best presented and used as a basic stage-by-stage progression.

The matrix is particularly useful in addressing training obstacles. Trainers and learners can ask themselves: "What stage is the learner at and what is preventing the learning from progressing?"

In this way the conscious competence theory helps trainers and learners to understand far better why an obstacle exists, and how best to deal with the challenge.

And since the conscious competence theory forces analysis at an individual level, the model encourages and assists individual assessment and development, which is easy to overlook when so much learning and development is delivered on a group basis.

We each possess natural strengths and preferences, (due to brain-type, and personality, and life-stage/experience, etc) and this affects our attitudes and commitments towards learning, as well as our abilities in developing competence in different disciplines. People begin to develop competence only after they recognise the relevance of their own incompetence in the skill concerned. Certain brain-types and personalities prefer and possess certain aptitudes and skills. We each therefore experience different levels of challenge (to our attitudes and awareness in addition to pure capability) in progressing through the stages of learning, dependent on what is being learned. Some people will resist progression even to stage 2 (becoming aware of incompetence), because they refuse to acknowledge or accept the relevance and benefit of a particular skill or ability. Denial may also be a factor where there is a level of personal fear or insecurity. Other people may readily accept the need for development from 1 to 2, but may struggle to progress from 2 to 3 (becoming consciously competent) because the skill is not a natural personal strength or aptitude. Some people may progress well to stage 3 but will struggle to reach stage 4 (unconsciously competent), and then regress to stage 2 (consciously incompetent) again, simply through lack of practise. We see this last scenario very commonly in the teaching of new computer skills, or the use of complex machinery, and in such situations the conscious competence theory quickly enables a reliable analysis of what the problem is, and how to rectify it.

The conscious competence model can be useful in all sorts of training situations. You will see other applications when you explore the definitions and progressions outlined in the matrix here.

| competence | incompetence | |

| conscious |

3 - conscious competence

|

2 - conscious incompetence

|

| unconscious |

4 - unconscious competence

|

1 - unconscious incompetence

|

Fifth Stage

As with many simple and effective models, attempts have been made to add to the conscious competence model, notably a fifth stage, which is commonly represented, among other suggestions, as:

'Conscious competence of unconscious competence', which describes a person's ability to recognise and develop unconscious incompetence in others.

Arguably this is a development in a different direction: ability to recognise and develop skill deficiencies in others involves a separate skill set altogether, far outside of an extension of the unconscious competence stage of any particular skill. As already mentioned, there are plenty of people who become so instinctual at a particular skill that they forget the theory - because they no longer need it - and as such make worse teachers than someone who has good ability at the conscious competence stage.

Alternatively, a fifth stage of sorts has been represented as follows:

"One will only know a maximum of 80% of anything ... and the remaining 20% is never the same." (Thanks to W McLaughlin for this, who suggested separately that 'Bateman' may be the source of the conscious competence model itself.)

Here are other contributions to the subject of a possible fifth stage of the conscious competence model, most recent last:

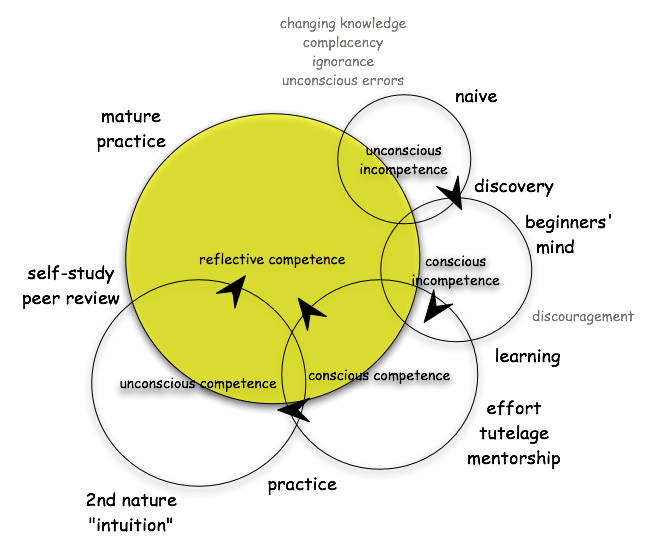

From David Baume: David wrote, May 2004: As a fifth level, I like what I call 'reflective competence'. As a teacher, I thought "If unconscious competence is the top level, then how on earth can I teach things I'm unconsciously competent at?" I didn't want to regress to conscious competence - and I'm not sure if I could even I wanted to! So, reflective competence - a step beyond unconscious competence. Conscious of my own unconscious competence, yes, as you suggest. But additionally looking at my unconscious competence from the outside, digging to find and understand the theories and models and beliefs that clearly, based on looking at what I do, now inform what I do and how I do it. These won't be the exact same theories and models and beliefs that I learned consciously and then became unconscious of. They'll include new ones, the ones that comprise my particular expertise. And when I've surfaced them, I can talk about them and test them. Nonaka is good on this (Nonaka, I. (1994). "A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation." Organization Science 5: 14-37. (David Baume, May 2004).

And from Linda Gilbert along similar lines, May 2004: Responding to your inquiry about "fifth stage of learning model" on your conscious competence learning model webpage... I've heard of one that belongs - I think it was called "re-conscious competence." It indicates a stage where you can operate with fluency yourself on an instinctive level, but are ALSO able to articulate what you are doing for yourself and others. That stage takes attention to process at a meta-cognitive level. Many people never reach it - we all know experts who can't tell you how they're doing what they're doing. (Linda Gilbert, Ph.D., May 2004) If you can shed further light on origins of this thinking please get in touch.

And from John Addy, Aug 2004: "I suggest the 5th stage can be 'complacency.' That is, when the person continues to practise the skill which has become automatic and second nature, but, over time, allows bad habits to form. For example, an exemplary driver makes a silly mistake. Or, a trainer, believing himself or herself to be an expert, fails to prepare adequately for a training session and drops a clanger. These are the dangers of thinking you can do something so easily, you become complacent. Complacency can also cause problems if the person doesn't keep up-to-date with the skill. As techniques and approaches move forward, the person remains behind using set methods which have perhaps become stale, out-dated or less relevant to today. In each case above the person must reassess personal competence (perhaps against a new standard) and step back to the conscious competence stage until mastery is attained once again. Complacency provides a useful warning to those who think they have reached the limit of mastery. It can also encourage people to search for continuous improvement." (John Addy, Aug 2004)

From Lorgene A Mata, PhD, December 2004: "First, I think calling this model 'conscious competence learning model' is not appropriate or accurate because it gives the impression that the model considers conscious competence as the highest level of learning when in fact, it is only the third level. Based on this model, it is 'unconscious competence' that is the end-goal of learning. But, calling the model unconscious competence learning model may not sound fitting either. I therefore suggest to call this model simply as 'competence leaning model' without the qualifying term 'conscious'. Secondly, I find this model applicable mainly if not exclusively to the acquisition of physical skills or competencies and not to higher mental skills where conscious, non-repetitive, complex and creative mental operations are demanded. Thirdly, I believe the highest level of competence learning is not level 4, 'unconscious competence', but a higher 5th level which I call 'enlightened competence'. At this level, the person has not only mastered the physical skill to a highly efficient and accurate level which does not anymore require of him conscious, deliberate and careful execution of the skill but instead done instinctively and reflexively, requiring minimum efforts with maximum quality output, and is able to understand the very dynamics and scientific explanation of his own physical skills. In other words, he comprehends fully and accurately the what, when, how and why of his own skill and possibly those of others on the same skill he has. In addition to this, he is able to transcend and reflect on the physical skill itself and be able to improve on how it is acquired and learned at even greater efficiency with lower energy investment. Having fully understood all necessary steps and components of the skill to be learned and the manner how they are dynamically integrated to produce the desired level of overall competence, he is thereby able to teach the skill to others in a manner that is effective and expedient. You wrote in your website that this 5th level may be called 'conscious competence of unconscious competence'. But to me, this term is too complex and unwieldy to most people. My suggested label which is 'enlightened competence', I believe, is more appropriate for this 5th level of competence that indeed exists and is attainable in some cases." (Lorgene A Mata, PhD, December 2004)

From Roger Kane, November 2005: "I have been aware of and using this four level model's concepts for a great number of years... But, I always felt that there was another level (level 5), based upon the skills of level 4, that reflected an ability to be reactively creative. That is, to do for the first time something never before considered. The ability to intuitively react to a new situation with an optimally accurate response. The "Wow, I didn't know I could really go to that level!" experience. I have occasionally happened upon this in both snow and water skiing, tennis and driving race cars when there was no time to think about how to solve a new puzzle, but my instinctive reaction did so. I have also seen skiers I coach momentarily get there without understanding why or knowing how to get back there. I suspect this is what is often referred to as 'being in the flow' or 'in the zone' and is more dependent on 'allowing' and holistic trust of the 'body genius' rather than causing from linear thoughts or inputs. While potential for this level 5 of performance can be trained and prepared for, few can produce it on demand (i.e., Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods). The foundation definitely lies in level 4 but the results are expressed as the ultimate performance potential of an individual." (Roger Kane, Director of Education and Training Sunburst Ski Area, Kewaskum, Wisconsin, November 2005)

From Mike McGinn, December 2005: "Another suggested parallel for a further stage beyond 'unconscious competence'... The Capability Maturity Model* has echoes in numerous disciplines, and I would suggest that 'optimizing unconscious competence' or something similar could be appropriate. This to me would encompass the unconscious operation of the process or delivery of the task alongside the unconscious measurement and improvement of the task delivery process. Perhaps that also introduces another whole layer of variables, though- whether it is helpful or not is moot!" [*The Capability Maturity Model was it seems developed by the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie-Mellon University; it describes five stages of maturity: 'Initial, Repeatable, Defined, Managed, Optimized', and is a protected system belonging to the US Mellon financial services corporation.] (Mike McGinn December 2005)

From Andrew Dyckhoff, January 2007: "My suggestion for the 5th level would be 'Chosen Conscious Competence'. People often use the driving analogy to explain the model. In the analogy people normally relate the transition from a learner having to think: mirror, signal, manoeuvre, engage, etc., to jumping in and driving off without consciously thinking about the process. When we go on an advanced driving course we learn that there are certain things we should ALWAYS CONSCIOUSLY CHECK. These include looking to see whether there is an idiot coming the other way through a red light, and stopping so you can see the road behind the tyres of the car in front of you, etc. The sales example is that excellent sales people discipline themselves never to assume and always to check.. To summarise, there are some elements of what we do that are so critical to successful performance that the highest level of learning is to choose to remain consciously competent, as with the advanced driving analogy: unconscious competence is fine when we are changing gear, but not when passing through a green light..." (Ack Andrew Dyckhoff, January 2007)

From Will Taylor, March 2007: "Re '5th stage' - see the ideas in the diagram. This is more of a spiral model than a hierarchical matrix. It would seem that mature practice involves a mature recognition that one is inevitably ignorant of many things one does not know (i.e., we revisit 'unconscious incompetence' repeatedly or continually; i.e., 'consciousness of unconscious incompetence'). Repeatedly, we are continuously rediscovering 'beginner's mind'.

"We revisit conscious incompetence, making discoveries in the holes in our knowledge and skills, becoming discouraged, which fuels incentive to proceed (when it does not defeat). We perpetually learn, inviting ongoing tutelage, mentoring and self-study (ongoing conscious competence). We continually challenge our 'unconscious competence' in the face of complacency, areas of ignorance, unconscious errors, and the changing world and knowledge base: We challenge our unconscious competence when we recognize that a return to unconscious incompetence would be inevitable. We do this in part by self-study and use of peer review - such that mature practice encompasses the entire 'conscious competence' model, rather than supercedes it as the hierarchical model might suggest."

(Courtesy of Will Taylor, Chair, Department of Homeopathic Medicine, National College of Natural Medicine, Portland, Oregon, USA, March 2007. Please reference the diagram accordingly if you use it.)

And these wonderful observations from from Richard Moore, May 2007: "...I studied with Chris Argyris at Harvard and always had a bit of discomfort at his notion of 'incompetence.' Most people will not acknowledge that they are incompetent. They will, however, acknowledge that they are unaware, possibly ignorant of something, or simply unmotivated by it. Indeed, until one has a purpose for a thing, it is simply irrelevant. That then introduces the issue of power relationships, a debate I had with Chris. If one person defines another as 'incompetent,' but the other sees no need for the 'competence,' then the one is imposing a worldview on the other, which if permitted to prevail is essentially imperial - or at the least, dominating. This fits the model which Paulo Freire critiqued in Pedagogy of the Oppressed and his other works. In the spirit of a 'liberating praxis' and related notions of empowerment through one's ability to define one's world and one's self and relations within it, I would propose 5 stages somewhat along the lines of Will Taylor's: accidental, intentional, skillful, masterful, and enlightened. The accidental stage is simply the stage in which one recognizes no particular need for a skill or competency, but may come across it accidentally nonetheless. Whether one chooses or comes to value it is determined by an intentionality or willful choice ('desire'). That intentionality then can lead to skillfulness. Skillfulness can become mastery. Mastery has the potential for enlightenment.

I would not call mastery 'unconscious.' It is simply 'wired in.' That, literally, occurs when the neuro-cognitive system acquires new brain cells (e.g., see https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7431209&sc=emaf). This does not mean that one is 'unconscious' but that one's responses become automatic; about which, one can be highly conscious. Consequently, 'enlightenment' is an appropriate label for the stage beyond 'mastery.' This can also be called 'reflective,' although one is often reflective beginning with intentionality. The distinction is that 'enlightenment' represents a particular attainment of higher awareness, whereas reflection per se is the directing of attention toward an object. I would emphasize the nature of enlightenment as a dissolution of boundaries to the point where one is conscious of a higher level of reality in which self and other become part of a unified field, albeit from the point of awareness of an enlightened master, as it were. This is that form of mentoring referred to as guruship (assuming the guru is, in fact, qualified through this degree of enlightened competence).

What should be apparent is that there is learning distinct from awareness. One 'learns' through means independent of awareness, although awareness may accompany learning. Awareness can also interfere with learning. The two are simply not the same. One may in fact be a capable teacher with awareness and lack the actual skill one is teaching. This may be unusual, but is certainly not unheard of. It can arise with persons who become disabled, but are still aware, or it may arise with persons who are aware but never acquired the physical skill. Certainly Einstein was never 'God' to have thought experiments enabling him to imagine how 'God' might have designed the universe. More illustratively, athletes can improve their performance through visualization. Visualization, in fact, can improve the efficacy of exercise in general, whether physical or mental. This should be telling us that awareness and the physical process of learning occur somewhat independently, albeit interactively.

Anyhow, I suggest that 'conscious competence' is really just 'learning' in 5 stages, from accidental to enlightened, passing through intentional, skillful, and masterful. Many other labels can be applied, as many other cultures have done. The learning must be accompanied by a corresponding degree of awareness that then differentiates automatic learning from sentient learning. We can 'teach' a machine, but enlightenment requires some degree of 'spiritual' transcendence or insight. Whether artificial intelligence can attain this is of less concern than the simple acknowledgement in functional or operational terms that 'enlightenment' is attained through intentionality that unifies mastery with awareness - even if the mastery in physical terms is exhibited by someone or something other than the enlightened master (shades of 'the Force'). Effective leaders in organizations accomplish this through the organizations. Gurus accomplish this through their disciples. I would also remark, in closing, that Buddhism distinguishes the Arhat from the Boddhisattva. Both are considered 'enlightened,' except the Arhat is essentially selfish about attaining nirvana, whereas the Boddhisattva sticks around to bring everyone else along. One might ask if it is truly 'enlightened' to cash in on nirvana without mentoring others. This is the essential distinction between Hinayana, or 'small boat (or vessel),' and Mahayana, or 'big boat (or vessel),' in regard to schools of Buddhism. I like the idea that an 'Enlightened Master' is one who acts compassionately toward others by mentoring them."

And a follow-up note from Richard on five stages:

Evelyn Underhill, in her classic work Mysticism, identifies five stages of development:

1. Awakening

2. Purgation

3. Illumination

4. Dark Night of the Soul

5. Union with the Ultimate

(Courtesy of Richard H Moore, US Dept of Energy Professor, Assistant Professor of Behavioral Science, Leadership and Information Strategy Department, Industrial College of the Armed Forces, National Defense University, Washington, DC, May 2007. Please reference Richard Moore if you use any of his comments.)

Here is another helpful and interesting perspective from Mussarat Mashhadi, December 2007: "... I feel there is another stage which is important; this I believe is the stage in which a person having reached the fourth level is capable of enhancing the same skill or may be if required has the ability to retrace his learning in order to develop a new set of skills for the same function (type writer vs. computer). So maybe the fifth level can be enhancement and enrichment stage. For example people who are computer savvy have to every other month learn, unlearn or relearn (Toefler, 1991) one or the other skill. To be able to achieve this there has to be in my opinion, an acceptance about personal limitations and receptiveness to learn. Having a high self efficacy (Bandura) might be a factor restricting a person to the fourth stage only...." (Ack Mussarat Mashhadi, December 2007)

S Baker posed this questioning observation (March 2008), to which I've added my response afterwards: "... I have made my living in the equine industry for better than 38 years. I am now involved in instruction and clinics about riding skills to a high level. I have a saying that I came across and use frequently because I run into a lot of people it fits. 'The greatest obstacle to discovery is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge' by Daniel J. Boorstin. Hence people that think they know something or everything and can't/won't learn something new. I don't doubt I've been there myself. Hopefully I'm into learning and growth pretty consistently. Where does that fit in with the four stages of competence?..." My (AC's) reply was: "I would say it's either a (usually, but not always) negative aspect of unconscious competence, or a fifth stage (albeit not inevitably following the prior learning), or perhaps more appropriately stage one (unconscious incompetence) of a new learning cycle - unconscious due to ignorance or denial - since the ignorance concerns a new form of competence or capability."

The above exchange prompted this from C Thompson (April 2008): "...I think the stages are fixed places where people are at a point in time on a specific topic. People can move through the stages but there need to be certain elements present for this progression to take place... they would include the environment for learning, the teacher's skill and style, and most importantly the student's interest in and reason for learning. There are probably many other elements. So back to the quote, the person that "knows" (the illusion of knowledge) does not need to learn. When a person thinks they are full of knowledge there is no room for more knowledge and learning stops or is slowed considerably. Progression from one stage to the next stops or is slowed considerably. I think this refers less to where someone is and more toward where they are capable of going..."

This helpful and elegant interpretation of the 5th stage of the Conscious Competence learning model was submitted by G Sharples (June 2008): "... I was reading your contributors' discussions regarding the 5th level of learning and thought I'd join in with my own definition: The 5th level is achieved when the individual is able to perform consistently at Level 4, and then de-construct their experience for both themselves and others, so each may learn to apply the skill consistently. I like the suggestions that this stage is called Enlightened Competence..."

The following observations are from S March (Feb 2009), which my (AC) reactions beneath: "... Re the 5th Step (and beyond): Is there any any additional element to describe a Reflective Competence practitioner who knows that, whilst the current job practice is as good as is available, there must be a better way to do something - i.e., the eventual output is product/service innovation that revolutionises the way the world regards and uses the product or service. This approach may well involve disregarding the knowledge that has led to the practitioner's current scale of competence, and possibly requires assumption of a conscious incompetence state (though conscious incompetence is not a flattering, or indeed, accurate label for such an experienced and knowledgable practitoner) so that the problem can be viewed without any pre-conceptions?..."

The above is an interesting question. The scenario raises the possibility that learning a new method/skill (in response to external innovation or demands for example) for an existing area of conscious/reflective competence might suitably be regarded as the start of a new Conscious Competence cycle. The last 4th/5th stage of the first cycle is for many people the early stage(s) of a new cycle of learning in new methods. Conscious Competence in an existing skill can easily equate to Unconscious Incompetence in a new method now required to replace the hitherto consciously competent capability. The Refective Competence level (suggested fifth level - see Will Taylor's diagram above) in the first cycle could equate to the Consciously Incompetent level in the new cycle. Reflective learners possess expert competence in the subject at a determined skill or method, but not in different and new methods. So perhaps representing the learning of new methods for existing expertise (at say level 4 or 4) in terms of a repeating 4/5-part cycle is a reasonable way to approach the 'response to external innovation' scenario, or 'internal innovation' for the same reasons.

The observations which follow are from M Singh (23 Feb 2009): "...I have read the discussion especially with reference to the 5th stage, and have tried to integrate J M Fisher's theory of the Process of Transition to add extra emotional perspective. When someone becomes conscious of incompetence, emotions of 'anxiety', 'happiness', 'fear' and or 'denial' may be experienced. Feelings of 'threat' (to previous learning), 'guilt' (at departing from previous learning) and possibly 'depression' (at having to relearn) can arise until a firm commitment is made to the new learning. If the commitment to the new learning is not strong, feelings of 'hostility' or 'disillusionment' can arise. The ability to demonstrate the skill partially is the beginning of a 'gradual acceptance', which through practice then naturally leads to Conscious Competence. A lack of discipline in this area could repeat emotional sequences of earlier transitions. Mastery at this stage enables Unconscious Competence and builds confidence to teach others the skill. This is arguably the fifth 'reflective' stage. The Cognitive Domain of Blooms Taxonomyoffers further useful perspective, by which we can overlay the Bloom Cognitive Domain learnings stages onto the Conscious Competence stages: Bloom's 'Recall' and 'Understand' knowledge fall within Conscious Incompetence. 'Application' is within Conscious Competence. 'Analysis' is within Unconscious Competence. The 'create and build' aspects of 'Synthesis' equate to what some suggest is a 5th stage of the Conscious Competence model. Bloom's 'Evaluation' is a step beyond this - moving to objective detachment from the subjective involvement present up to and included in the Bloom 'Synthesis' stage, equating to the fifth 'reflective' stage of the Conscious Competence model. At the higher end of the reflective stage, mastery can be directed outwardly towards innovation for a wider (not self-directed) purpose, in which the master is critical of even his own achievements. Two driving factors here are concern for the greater good and humility regarding success of self." (Edited and abridged from a longer piece entitled 'Emotions in the Conscious Competence learning Model' from, and with thanks to, Maanveer Singh, CPBA, Kingfisher Training Academy, Mumbai, India, 23 Feb 2009.)

I received this amusing contribution from Dr V Kumar (19 Apr 2009): "...Some 20 years ago, a colleague suggested to me that the 5th stage in the Conscious Competence cycle should be 'Confident Incompetence'. He was referring to some of our professors and senior teachers, somewhat past their prime..." The joke is a warning of the dangers of lapsing into complacency after attaining mastery in anything, and is therefore a very useful point.

And this, from Lee Freeman (May 2009): "...Regarding the conscious competence model, I came up with this little thought... 'The unconscious incompetent doesn't know he's incompetent and when he is competent, is unconscious of his competence. And when his meta-conscious competence imparts vigilant omniscience, truly he's a fool when he believes he's omnipotent! Or maybe he's just unconscious of this…"

Here are interesting comments from Charles H Grover (March 2010): "...I have been reading the discussions about adding a 5th step to this model, and suggest that the first four are simply out of step. I refer you to the 'He who knows not...' proverb(below). The old Confucious/Persian/Arabic saying has step three (Conscious Competence) as the ultimate, while step four (Unconscious Competence) is the person asleep, and he/she needs to be woken up. I believe this really makes Will Taylor's excellent diagram clearer; discovery, learning, practice, mentorship. Who are we to hold their hands when they are inviting us to climb on their shoulders? A fifth stage is easier to define when we get the first four in order..."

From Mike Nichols, Oct 2013: "...I have competed at a high level in basketball and use the learning model with the players I now coach to raise their awareness of learning new skills on the court... they feel enlightened when they understand how they learn. As a player reaching a certain level of ability, the term 'in the zone' or 'unconscious' crops up, meaning the player is hitting shots from all over the place as they unconsciously score from silly angles. This is more than 'unconsciously competent' and I suggest this next stage is 'unconsciously super-tuned'. I have experienced this several times (but not often enough for my own liking...) and there is no better feeling than being unconsciosuly super-tuned. I would move my body, dribble the ball, analyse the defense, take note of my team mates and while processing all this information, I would take a shot, knowing only the general direction of the basket, yet the mechanics of my body either from muscle memory or instinct would ensure the ball ended up in the hoop. Of course when a player becomes conscious of being in this new state, he/she begins to think about the shots and invariably then misses the next one! (Mike Nichols, Emotional Intelligence coach at mindfulnessperformance.co.uk)

If you've seen or have thoughts about the competence competence fifth stage that are worthy of the model or can provide further information about or expand on any of the suggestions here, please get in touch.

Origins

The earliest origins of the 'conscious competence' learning concept are uncertain. Various theories and maxims - some very old - could potentially have inspired the model. Ancient sources such as Confucius and Socrates are cited as possible early originators of seminal thinking and writings relating to the 'conscious competence' model, together with more recent authors and academics.

In August 2013 I was informed (thanks Earl L Wiese, Jr., owner of ProTek Statistical & Quality Consulting and Training) as to perhaps the earliest definition of the Conscious Competence learning model in its modern form, namely by Martin M Broadwell, the author of the article titled 'Teaching for Learning' in The Gospel Guardian, dated/published 20 February 1969. I am seeking clarification and further details about this which will be published here when available.

Here is the text from The Gospel Guardian, according to digital online copy. The original hard-copy paper was published 20 February 1969:

Here is some information about The Gospel Guardian, from the website www.wordsfitlyspoken.org, which offers the electronic copies of The Gospel Guardian and related materials:

"The editors of Gospel Guardian deliberately neglected to apply copyright to the [Gospel Guardian] periodical, relegating it to public domain. Out of respect for their principles and the value of their writings, we likewise release all rights to all material on this page, releasing it to the public domain."

And this, from 1983 edition of The Gospel Guardian:

"The Gospel Guardian was originally started by Foy E Wallace, Jr in 1935. Due to various difficulties, publishing ceased for some period of time. However, interest and energies were eventually renewed and publishing resumed under an updated format and name, The Bible Banner. The motivations, history, and desire for the papers are best described in their own words, The Bible Banner - Past Present And Future, when the Bible Banner temporarily converted from a monthly paper to a quarterly. Despite the hardships that the 1940's saw, The Bible Banner flourished. Eventually, interest peaked such that the monthly journal became a weekly paper. Not only did the format change, but so did the name. The paper resumed its previous name, The Gospel Guardian. The new paper saw editorial responsibilities shift to Fanning Yater Tant, son of J. D. Tant. Roy Cogdil's role as publisher and contributor both solidified and increased respectively. Other well known names faded while more recent names came into focus. In later years, the Gospel Guardian merged with Truth magazine. The combined circulation presented a newly named paper, The Guardian of Truth for several years, which was later renamed back to just Truth Magazine."

Besides the Gospel Guardian/Martin Broadwell origin, there have been two other major claims for the authorship of the model as we know it today - by Gordon Training International, and secondly by W Lewis Robinson. Obviously both of these claims are pre-dated by the 1969 Gospel Guardian/Martin Broadwell material.

A specific claim to authorship and definition of the modern-day 'conscious competence' model is found in a technical paper published in July 1974: 'Conscious Competency - The Mark of a Competent Instructor', which attributes the 'Conscious Competency' theory to W Lewis Robinson, then vice president of industrial training for International Correspondence Schools, of the USA probably. The full official reference for this source is: "Conscious Competency - The Mark of a Competent Instructor - The Personnel Journal - Baltimore , July 1974, Volume 53, PP538-539 - [supplied by The British Library - Shelf Mark 6428.065000]" (I am grateful to A Walter for his help with this in Jan 2013, in addition to the note I received about the possible attribution to Robinson below from D Hurst.)

The Robinson material/attribution refers to 'Competency' rather than 'Competence' but is otherwise broadly consistent with what we know of the model nowadays. A copy of the article follows in the panel below. N.B. If you use this article you do so at your own risk. It is made available here for educational and research purposes and is not a resource for free publication. Where and if you use the article below I urge you to reference it properly.

|

CONSCIOUS COMPETENCY - THE MARK OF A COMPETENT INSTRUCTOR (THE PERSONNEL JOURNAL - Baltimore. JULY 1974 VOL 53 PP538-539 - from The British Library - Shelf Mark 6428.065000) (It begins..) "A problem with many industrial training programs is that instructors who are not trained to be instructors are often too competent to do a good job. So says W. Lewis Robinson, vice president of industrial training for International Correspondence Schools. In his experience, many instructors who are selected by companies to train new employees are often so advanced in their own work that they have become oblivious to time needs of the novice employee. In a sense, they are too competent to be instructors. "They know their jobs so well," explains Robinson, "that they no longer have to think about what they are doing. They have arrived at the point where they can perform a given task - unconsciously. They are competent, but they are unconsciously competent, and that's what makes them poor instructors. They no longer are conscious of the step-by-step process behind the successful completion of the task. Therefore, they cannot communicate properly to a trainee - to an individual who is consciously incompetent - about what it takes to do the job." In explaining his theory and how it relates to industrial training, Robinson cites professional baseball managers as archetypes of "consciously competent" instructors - the ideal trainers of personnel. "Many people wonder why great ball players rarely make good managers in the big leagues. I think the reason is really rather simple. They've become such great hitters that they no longer have to think about how to hit a ball. It has become second nature to them, a purely intuitive reflex. It is nothing for them to go out to the ball park day after day and bang out two or three base hits. "But it's the Ralph Honks and Danny Murtaughs and Dick Williams who became managers - guys who hit .250 or .270. Throughout their careers they were constantly trying to improve their hitting. They had to think about it - about how they were holding the bat and how they were distributing their weight at the plate, and whether they were lifting their heads. They were conscious of their inabilities and because of this became conscious of all the intricacies of body coordination behind a smooth swing. Consequently, they are able to communicate this knowledge to their own players as managers. "Upon mastering a skill, whether it's learning to operate a two-ton press or finger a C# chord on a guitar, we become consciously competent of that particular skill," says Robinson. "After a while, through repetition we become unconsciously competent of that skill. The procedural analysis an individual goes through in learning to play a guitar chord - stopping to think of which finger goes behind which fret, one string after another - is no longer necessary. The hand intuitively responds-to the chord symbol in one unbroken and unconscious motion. The danger is that it is possible to slip back to the primal stage of the learning process - that of 'unconscious incompetency'. " Stated academically, the individual, according to the ICS vice president, progresses through four definite stages in the learning process: I. unconscious incompetency 2. conscious incompetency 3. conscious competency 4. unconscious competency The newborn infant is a totally unconscious, incompetent being. The small child is incapable of performing any skill, and oblivious to the fact that he cannot tie his own shoes, for example. After observing his mother tie his shoes, he eventually will become aware of his incompetency. That, according to Robinson, is a very important step in the learning process, for at that point he acquires the desire to know — the desire to assert himself and overcome his own sense of inadequacy. If the child's mother is not sensitive to the child's own sense of inadequacy, if she does not take the time to explain to him, step by step (which if thought about is no easy matter for an unconsciously competent adult to explain), then he can become frustrated and his sense of inadequacy will become reinforced. The training process would be thwarted, not because of the child's lack of desire or potential to learn, but because of the mother's insensitivity to his needs. Robinson says many training programs fail for the same reason. Being unconscious of the new employee's own sense of incompetency, a company will bring in a new man and allow him to work alongside the best worker in the department, expecting that, as if by osmosis, the new employee will acquire the same degree of proficiency as the skilled worker. If the employee does not respond to such training, the company blames the failure on his inability to comprehend. What is not realized is that the skilled employee has advanced to Robinson's "unconscious competency" level. The ICS executive's theory contains another important implication for industrial training. Because most workers become unconsciously competent in their positions, they run the danger of regressing to a state of unconscious incompetency - a sort of occupational senility brought on by overt complacency on the part of the worker. This state, of course, is more symptomatic of the type of worker who has no desire to keep updated on his craft or field, who sees no need for additional study once lie has learned his trade. Because of this attitude, he is vulnerable to "unconscious incompetency," and can easily regress to the point where he is, for all practical purposes, an unconscious incompetent. This eventual gravitation on the part of the unconsciously competent employee toward unconscious incompetency underlines the need for continuous training and retraining programs. As in professional sports, this often means that the player must be retrained in the fundamentals of his game in order to make him consciously competent again. And, only the consciously competent can train the conscious incompetent, or bring the unconscious incompetent to an awareness of his backsliding. The ideal instructor must, above all, be totally conscious of the training process, step by step. He must be able to assess what the novice employee knows against what he needs to know to be able to perform at a given skill. He must view things through his own eyes, assume his own sense of consciousness and guide him along until, like Plato's cave people, he can see the way for himself. Such an approach to industrial training can do much to alleviate many employee relations problems resulting from poorly-established employee training programs, "The consciously competent instructor," Robinson explains, "will avoid friction situations created by the interlacing of novice and complacent employees. Often a skilled technician will not want anyone to learn to do his job as well as he can. Or his lack of patience with the new worker can cause him to have antagonistic feelings toward his management for subjecting him to what he is confident is a group of blundering idiots whose ignorance is hindering his own progress in his work, not to mention the anxieties suffered by the trainees, who no doubt are having second thoughts about joining such a company." "Ultimately," says Robinson, "management must become conscious of what it takes to train productive and competent employees. Training employees to be consciously competent is nothing more than management showing the employee the proper way toward personal career growth. And this is, of course, the foundation of corporate growth." CONSCIOUS COMPETENCY - THE MARK OF A COMPETENT INSTRUCTOR (THE PERSONNEL JOURNAL - Baltimore. JULY 1974 VOL 53 PP538-539 - from The British Library - Shelf Mark 6428.065000) |

I am open to further information about the above W Lewis Robinson attribution, and about W Lewis Robinson himself.

Quite separately and alternatively, Gordon Training International is considered by very many people to be the originator of the 'conscious competence' model, although the 1969 Martin M Broadwell/Gospel Guardian evidence seems to pre-date the Gordon Training claim:

The Gordon Training 'Learning Stages' model certainly matches the definitions within what we know as the conscious competence model, although it refers to the stages as 'skilled and unskilled', rather than 'competence and incompetence'. Interestingly many people prefer the words skilled/unskilled terms because they are less likely to offend people. Gordon Training have confirmed to me that they did use the terminology competent/incompetent prior to redefining the terminology, but they did not develop the matrix presentation of the concept, and it remains unclear where the 'competence' originally term came from, and whether it pre-dated the Gordon model, or was a subsequent interpretation. The California-based Gordon Training organization, founded by Dr Thomas Thomas Gordon, states (at time of researching this aspect in 2006) that their Learning Stages model (called 'The Four Stages for Learning Any New Skill') was developed by former GTI employee, Noel Burch 'over 30 years ago' (as at 2006). To what extent GTI and Noel Burch based their Learning Stages concept on earlier ideas is not clear - perhaps none, perhaps a little. Whatever, Gordon Training International has been a commonly referenced source in connection with the conscious competence ('skilled/unskilled learning stages') theory.

Here are some other suggestions and comments about the conscious competence model's origins.

N.B. The absence of any further comments on this webpage about these suggestions below means that I have been unable to acquire/confirm any more details about the suggestions. In the case of the (actually R not P) Dubin suggestion (1962, therefore highly intriguing) I acquired two old copies of this book and could not find the attribution/content suggested, and so concluded that the reference is incorrect.

Many people compare the Conscious Competence model with Ingham and Luft's Johari Window, which is a similarly elegant 2x2 matrix. Johari deals with self-awareness; Conscious Competence with learning stages. The models are different, and Ingham and Luft most certainly were not responsible for the Conscious Competence concept.

Some know the conscious competence matrix better as the 'conscious competence learning ladder', and I've received a specific suggestion (ack Sue Turner) that the learning model was originated in this 'ladder' form by someone called Kogg; however, this is where that particular trail starts and ends; unless you know better...

Some believe that W C Howell was responsible for Conscious Competence in its modern form - apparently the model can be found in W C Howell and E A Fleishman (eds.), Human Performance and Productivity. Vol 2: Information Processing and Decision Making. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1982. (Thanks A Trost) In any event this is later than the 1974 Robinson reference.

Other origin suggestions are as follows (the www.learning-org.com message board contains much on the subject):

Linda Adams, president of Gordon Training International suggested that the "Learning Stages (model) i.e., unconsciously unskilled, consciously unskilled, consciously skilled, unconsciously skilled ... was developed by one of our employees and course developers (Noel Burch) in the 1970s and first appeared in our Teacher Effectiveness Training Instructor Guide in the early 70s..."

The model has been a part of all of GTI's training programs since that time, but they never added a fifth stage, and did not devise the matrix representation, the origins of which remain a mystery. Separately Linda has kindly informed me (August 2006) that Noel Burch used the 'competence/incompetence' terminology prior to redefining it as 'skilled/unskilled' so as to fit better with their training. It is not known what Noel Burch's prior notions, or influences in developing the model (if there were any), might have been.

Kenn Martin suggested the originator is identified by Michael A. Konopka, Professor of Leadership and Management Army Management Staff College Fort Belvoir, Virginia, as being DL Kirkpatrick, 1971, (presumably Donald Kirkpatrick, originator of the Kirkpatrick Learning Evaluation Model) from 'A Practical Guide for Supervisory Training and Development', Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.

A suggestion attributed by Bob Williams to Paul Denley, who "... writes about his learning in terms of a movement from Unconscious Incompetence, Conscious Incompetence, Unconscious Competence and Conscious Competence........." goes on to say that "...Paul's reference to this model is: P. Dubin (1962) from Human Relations in Administration, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall."

Bob Williams also includes a suggestion by Susan Gair: "... I have been interested for a long time to know the source of this adult learning model (unconscious incompetence etc). I have a document which discusses it, and then cites Howell 1977, p38-40..."

Development and conflict resolution expert Bill McLaughlin suggests Bateman is the Conscious Competence model originator. Any additional information about this would be gratefully received. (See Tony Thacker's comments below.)

David Hurst, Ontario-based speaker, writer and consultant on management, has looked for origins of the conscious competence model, and suggests that the first mention he could find was in an interview with W Lewis Robinson in the Personnel Journal v 53, No. 7 July 1974 pages 538-539, in which Robinson cited the four categories (UC/IC, C/IC, C/C and UC/C) in the context of training, and pointed out that UC/C practitioners often weren't effective as teachers. Hurst says the next mention was in an article by Harvey Dodgson "Management Learning in Markstrat: The ICL Experience", Journal of Business Research 15, 481-489 (1987), which used Kolb's learning styles and then showed the four conscious competence categories in a cycle but gave no references for it. Hurst corresponded with Dodgson but never got to the bottom of where the model came from. Hurst says also that Maslow has been suggested as a possibile original source but that he's not been able to find reference in Maslow's principle works.

And from Andrew Newton, UK consultant trainer (Jan 2005): "When I came across the conscious competence model, it seemed to fit my counselling skills development: Initially couldn't do it and was unaware that I couldn't (unconscious incompetence). I then trained with Relate and realized I wasn't very good (conscious incompetence). I worked hard and improved (conscious competence) until I found increasingly that I did this naturally in my work with colleagues and students (unconscious competence). I continued to use these skills (I thought, quite effectively) but realized years later, when I went on more training, that I was in fact quite rusty and had regressed into unconscious incompetence again (from 4 to 1). I would suggest that, unless you are a reflective practitioner, you run the risk of this dramatic shift (how many car drivers are not as good as they think when they have been driving for 30 years?). This may be similar to David Baume's 'reflective competence'. " (Ack A Newton)

Carole Schubert suggests (Jan 2005) the following: The unconsciously competent/consciously competent model I have known for many years as a skills development framework. I feel that a final category adds completeness, and use the analogy of learning to drive a car to explain it:

non-driver = unconscious incompetence

beginner = conscious incompetence

just passed driving test = conscious competence

driver who gets to work without remembering the drive (or drunk driver!!) = unconscious competence

The fifth level is the advanced driver who is processing what is happening 'in the here and now' without their cognisance interfering with their abilities; understanding why they are doing what they are doing and making conscious subtle changes in light of this understanding. Carole Schubert also points out a reference by worldtrans.org to the fifth level, which the unidentified writer calls: 'meta-conscious competence', whereby a capability is mastered to the point that the practitioner is consciously aware at all times of what unconscious or sub-conscious abilities he/she is using, and is able to analyse, adapt and augment their activity in other ways.

This interpretation is consistent with many other people's ideas that the fifth level represents a level of cognisance, which is above and beyond the fourth level of 'subconscious automation'. Furthermore, (Carole Schubert is another to suggest that) Dr Thomas Gordon, founder of Gordon Training International, originally developed the Conscious Competence Learning Stages Model in the early 1970s, when it first appeared in Gordon's 'Teacher Effectiveness Training Instructor Guide'. Its terminology was then unconsciously unskilled, consciously unskilled, consciously skilled, unconsciously skilled, and there was no fifth level. (Ack C Schubert)

And this train-the-trainer perspective, from James Matthews (Feb 2005), who points out that bringing skills back into (keeping skills at) conscious competence is necessary where a person needs to maintain vigilance, or needs to do something different, notably correct bad habits, or to keep skills fresh and relevant. In these cases moving skills from unconscious competence into conscious competence is a necessary step. Indeed certain types of skills - especially those which concern safety - should arguably be maintained within the consciously competence stage, and never be encouraged to 'progress' to unconscious competence. (Ack James Matthews)

This from Marcia Corenman (Feb 2005): "The Performance Potential Model bears a resemblance to the Dimensional Model that was developed in the late 1940's by psychologists Coffey, Freedman, Leary, and Ossorio. In the 1950s the Kaiser foundation and the US Public Health Service sponsored research projects which were published in 1957. Since then the Dimensional Model has been demonstrated as a valid classification of interpersonal behavior and is a dependable tool for understanding that behavior. I learned about this model in a book 'Leadership Through People Skills' by Robert E. Lefton, Ph.D., and Victor R. Buzzotta, Ph.D. © 2004 by Psychological Associates, Inc." (Ack Marcia Corenman)

Anita Leeds suggests (Mar 2005) points out the similarity and potential influence of RH Dave's 'Psychomotor Domain' learning stages model (1970), used in teaching manual skills and part of Bloom's Taxonomy, and which provides an interesting comparison alongside the conscious competence four-stage model: According to Dave's theory, the psychomotor learning domain emphasises physical skills, coordination, and use of the motor-skills. Development of these skills requires practice and is measured in terms of speed, precision, distance, procedures, or techniques in execution. There are five major categories in RH Dave's model, whose five stages, given certain learner attitude and circumstances, could just about be argued overlay the four stages of the conscious competence model:

- Imitation: Observes and patterns behavior after someone else. Performance may be of low quality.

- Manipulation: Performs skill according to instruction rather than observation.

- Develop Precision: Reproduces a skill with accuracy, proportion and exactness; usually performed independently of original source.

- Articulation: Combines more than one skill in a sequence, achieving harmony and internal consistency.

- Naturalization: Has a high level of performance. Performance becomes automatic. Completes one or more skills with ease. Creativity is based on highly developed skills.

Rey Carr adds (Mar 2005): "Back in the early 1970s I taught classes called Parent Effectiveness Training. I was trained as an instructor by (and is another to suggest) Tom Gordon, probably now called the Gordon Effectiveness Institute. Trainers often met together to discuss various issues associated with experiences and improving the curriculum. One of our group talked about four learning stages as unconscious incompetent through unconscious competent. However, I came up with a different model at the time because we thought the language of that four stage model might be too jargon like for the parents we worked with in the classes. The model I developed, which we then adapted for our training materials was also a four stage model, but the stages were (are) unskilled, skilled, competent, expert. In the unskilled stage the learner didn't know what to do, why it might be necessary or valuable to use the skill and if they did try it, would give up very quickly if encountering any difficulty whatsoever. In the skilled stage the learner would be able to perform the skill with some consistency, but often did so in a robotic or formulaic fashion. In the competent stage the learner was able to perform the skill with great consistency, but was mostly a clone of the person who taught them how to do it. The learner strongly resisted alternative ways to perform the skill and was strongly connected to the original teacher. In the expert stage the learner finally found his or her own voice or style and was continually modifying the skill to fit circumstances, new learning, and context. Thus while the group of us started out using the unconscious competence model, eventually each of us (like myself) went past the wording of the model and became "expert" in learning stages (no longer needing to explain it the same way we originally heard it..)" (Ack Rey Carr)

Jillian Duncan suggests (April 2005) the conscious competence model relates to the work of Professor Albert Bandura, a pioneer of socil cognitive theory, human efficacy and 'mastery'. (Ack J Duncan) [Following on from this suggestion I asked Professor Bandura for his comments about the origins of the conscious competence model and he replied (15 Apr) "I am not familiar with the model you describe," which effectively eliminates Professor Bandura from the list of possible originators... (AC)]

And another reference to Tom Gordon (from Ingrid Crosser, Australia, April 2005) "... Regarding your question about the origins of the Conscious Competence Learning Model, it might help you to know I came accross the same concept with slightly different wording in the Parent Effectiveness and the Teacher Effectiveness Training courses by Thomas Gordon in the late 70s. It was referred to as the Unconsciously Unskilled to Unconsciously Skilled stages of learning. I still use it today in my group work with parents regarding parenting. (Ack Ingrid Crosser)

Tom Gagnon wrote (April 2006) "I have experienced the 'conscious-competent' material here in Minnesota, USA. It is used for sales training at the Larry Wilson Learning Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. I do not know if Larry Wilson developed the material or modified it to meet his training programs." (Ack Tom Gagnon)

Robert Wright suggests (July 2006) that the model can be traced back to Holmes and Rahe. (Holmes and Rahe are more usually associated with the Holmes-Rahe crisis/stress life changes scale - if anyone has knowledge about any work of theirs which relates to the conscious competence stages then please let me know).

Tina Thuermer (August 2006) is another suggesting Gordon Training origins: "I think what you are referring to is 'Gordon's Skill Development Ladder', which is used by Performance Learning Systems in training teachers in peer coaching. I have also used it with grad students becoming teachers, and with my 11th and 12th grade students. It's a staircase with the first one being 'Unconsciously Unskilled' (the fantasy stage - 'Oh, I can do this, I've been taught, teaching doesn't look too hard'), the second being 'Consciously Unskilled,' (survival stage: 'Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into - this is so much harder than I thought.'), the third being 'Consciously Skilled' (or the competence stage: 'I know what to do, and I am concentrating very hard and on a very conscious level to use the techniques I know I need to be successful') and the final, one, Unconsciously Skilled (mastery stage: 'I don't have to be consciously operating all the time - some of the techniques and practices I have acquired are now wired into me, some of my skills are automatic - I can save my conscious energy for the ones I'm still working on developing.'). He (or she) also posits the existence of the 'Unconsciously Talented' - those annoying people who are really good at something from the beginning - they are wired for that activity." (Ack Tina Thuermer, Washington International School, Washington DC)

Tony Thacker made the following contribution (October 2006) in reference to the above comments about Bateman being a possible origin. "In the item on the four stages of learning (conscious competence model) you ask for references to 'Bateman'... Did your original informant perhaps mean Gregory Bateson? In 'Steps to an Ecology of Mind' (page 293) Bateson describes five stages of learning: 'learning three' seems to correspond to the process of becoming conscious of what is going on when we are operating in unconscious competence; Bateson's five stages of learning are:

- Zero learning is characterised by specificity of response, which, right or wrong, is not subject to correction

- Learning I is change in specificity of response by correction of errors within a set of alternatives

- Learning II is change in the process of Learning I, eg, a corrective change in the set of alternatives from which choice is made, or a change in how the sequence of experience is punctuated

- Learning III is change in the process of Learning II, eg, a corrective change in the sets of alternatives from which choice is made (Bateson goes on here to say that 'to demand this level of performance of some men and mammals is sometimes pathogenic')

- Learning IV would be change in Learning III, but, says Bateson, probably does not occur in any living organism on this Earth

Bateson quotes, pages 276-278, from an intriguing article on 'Deutero-learning in a Roughneck Porpoise' to illustrate progression through the levels." (Ack Tony Thacker, October 2006)

I shall resist the temptation to ask for further information about the 'Deutero-learning in a Roughneck Porpoise' article.

Sam Webbon offered this additional perspective: "...As regards the model's uncertain origins, the suggested link to Buddhism seemed fitting... True enlightenment involves acting compassionately towards and mentoring others... I like this ethic and can imagine that the author of the Conscious Competence model did too... The absence of ownership of the model is consistent with the Buddhist philosophy of sharing, mentoring and encouraging others, as would a bodhisattva..." (Thanks Sam Webbon, May 2010)

Thank you to all who have contributed so far to the debate above. Further suggestions and contributions are always welcome.

He who knows not...

Aside from these discussions, there are indications that the model existed in similar but different form. Various references can be found to an ancient Oriental proverb, which inverts the order of the highest two states:

He who knows not, and knows not that he knows not, is a fool - shun him, (= Unconscious Incompetent)

He who knows not, and knows that he knows not is ignorant - teach him, (= Conscious Incompetent)

He who knows, and knows not

that he knows, is asleep - wake him, (= Unconscious Competent)

But he who knows, and knows that he knows, is a wise man - follow him. (= Conscious Competent)

This is similar to the Conscious Competence model, but not the same. It is expressing a different perspective.

Gordon Training International (as they are now called) clearly originated their own version of this model in the early 1970s. However we do not know where and when the 'conscious competence' terminology originated, nor the origins of the 2x2 matrix presentation, and whether these aspects pre-dated of followed GTI's work.

If you know the origins of these aspects, or any other possible origins of the 'Conscious Competence' learning model, or you wish to add to the discussion about a 5th stage, please contact me.

Other Ideas

Prochaska and Diclemente

Initially developed in the field of personal counselling and clinical therapy during the 1980s and 90s, Prochaska and DiClemente's personal change methodology is now adapted for various personal therapeutic, healthcare and clinical interventions, and is also transferable to facilitating personal change in work and management areas, especially for developmental situations, as distinct from mandatory or disciplinary situations which usually necessarily require a more prescriptive and firmer approach.

The 'Stages of Change' model was developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in association with their 'motivational interviewing algorithm', which is a staged and (suggested) scripted approach to therapeutic discussion or couselling - entailing key aspects of:

- validation of experience and feelings

- confirmation of decision-making control with the patient/subject

- acknowledgement of the reality of the challenge

- clarification of options and implications, and

- encouragement to progress in small steps,

- within which an assessment of the other person's readiness to attempt change is crucial.

For now, here's the basic structure of the Stages of Change model. I intend to present a more detailed interpretation of these ideas in the future, meanwhile this is a brief summary. The Stages of Change model very sensibly breaks down the dynamics and process of personal change into several steps that we can see as conditional and inter-dependent. Thus we are reminded that meaningful and sustainable personal change cannot be imposed or forced arbitrarily. Successful personal change depends on a careful response to individual situations and perceptions - in which the role of the helper or coach (or supervisor or manager or boss, whatever) is to assess, illuminate, inform, encourage and enable. There are actually some interesting overlaps with aspects of the conscious competence model.

The Prochaska and DiClemente stages of change are typically defined as:

- Pre-contemplation

- Contemplation

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance/Relapse

This is a beautifully elegant model, in which the steps make complete sense, and as importantly, the responses and initiatives of the helper/coach are appropriate and pragmatic according to the stage and the individual. One might argue that this states the obvious for any coaching or change-enabling methodology, but sometimes the simplest things are not actually so simple to do without a reference of some sort.

Prochaska and DiClemente's stages of change theory forms the basis of the Transtheoretical Model - a more complex theory to be covered here separately in due course.

(My thanks to Elaine Krantz for raising Prochaska and DiClemente's work on personal change.)

Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFT)

A relatively modern methodology, growing in popularity. The concept and therapy can be practised one-to-one, or self-taught and self-applied. The emphasis is strongly on quick forward-looking intervention, contrasting with much traditional therapy which looks back and seeks to find problems and causes, which for many can become traumatic, negative, and painstakingly slow, not to mention expensive.

Instead SFT, or 'Brief Therapy', focuses on solutions and change, in an individual and pragmatic way.

There are clear overlaps with ideas found in NLP and hypnotherapy.

STEPPPA

The STEPPPA method (alternatively STEPPA) is represented by the acronym made from Subject, Target, Emotion, Perception, Plan, Pace, Adapt/Act. STEPPPA is a coaching model (notably in life-coaching in a business context) advocated by expert coach Angus McLeod, which is now central to much UK formal accredited life-coaching training. Based partly on NLP(Neuro-Linguistic programming) principles, the STEPPPA process entails:

- Subject - validating the subject (the issue or matter) that is the focus of the person being coached (coachee)

- Target - validating or helping to establish the specific target (or goal) of the coachee

- Emotion - ensure emotional context is addressed and resolved relating to the coachee, the issue, and the target, which if appropriate should be re-evaluated

- Perception - widen perception and choice in the mind of the coachee

- Plan - help the coachee establish a clear plan (process with steps, not choices),

- Pace - and pace (timescale and milestones); or perhaps a timeline that incorporates both plan and pace

- Adapt/Act - review plan, adapt if necessary, before committing to action.

Egan's three-stage change model

Gerard Egan's three-stage change model is used especially in coaching.

Essentially for enabling self or another person to:

- Explore personal history and reflect on opportunities.

- Explore what personal success would be like, suggesting choices, through considering results and implications.

- Decide and proceed with implementation according to what is realistic.

More coming. Contributions and expansion welcome. My thanks to Phil Nathan for raising this.

Erik Erikson

More detail is available on the Erik Erikson life stages page. Erik Erikson published his remarkable eight stage theory of human development in the 1950s. It is also referred to as the 'epigenetic principle', in which our passage through eight 'psychosocial crises' influences our growth and personality, ideally resulting in a tendency towards the positive possible outcomes at each stage.

| 1. | 0-1 yrs | Infant | Trust v Mistrust |

| 2. | 2-3 | Toddler | Autonomy v Shame/Doubt |

| 3. | 3-6 | Preschool | Initiative v Guilt |

| 4. | 6-12 | School | Industry v Inferiority |

| 5. | 12-18 | Adolescent | Identity v Role Confusion |

| 6. | 18-30 | Young Adult | Intimacy (relationships) v Isolation |

| 7. | 30-50 | Mid Adult | Generativity (giving) v Stagnation |

| 8. | 50+ | Late Adult | Integrity (acceptance) v Despair |

This is a brief summary of the model, not a full explanation. Ages ranges vary for different people.

Erikson's human development theory is a powerful model for parenting, teaching, and understanding self and other people, young and old.

Parallels can be seen with Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

Elisabeth kübler-ross's stages of grief

In detail on the Elisabeth Kübler-Ross 'Grief Cycle' page, essentially the model explains the stages of personal change related to impending death and dealing with bereavement - and all sorts of other personal traumatic change - as follows:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

(Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, 1969.)

Reynold

The learner passes through stages, each prompting a release of energy:

- help!

- have a go

- hit and miss

- sound

- relative mastery

- second nature

(Adapted by James Atherton, thank you James. See the wonderful teaching and learning materials on James Atherton's websites.)

Change Equation

Various interpretations exist. The basic idea is that people will only change when:

the combination of the desire for change, the vision of the change, and the knowledge of the change process is greater than the value of leaving things as they are.

This can alternatively be expressed as dissatisfaction + vision + change process = the cost of change (Managing Complex Change, Beckhard and Harris, 1987).

John Fisher

A more complex model involving positive and negative change options:

- anxiety (can I deal with this change that I'm facing) - potentially leading negatively to denial

- happiness (something's going to change)

- fear (of imminent personal change)

- threat (from reactions of others to the new 'me') - potentially leading to disillusionment

- guilt (for previous behaviour) - potentially leading negatively to depression and thereafter hostility

- gradual acceptance (I can see myself in the future)

- moving forward (this can work and be good)

See the John Fisher Personal Change webpage.

See the diagram. (Acrobat reader required - available free from adobe.com)

Related Materials

- BLOOM'S TAXONOMY OF LEARNING DOMAINS