Do not stand at my grave and weep

Do not stand at my grave and weep

Mary Frye's (attributed) famous inspirational poem, prayer, and bereavement verse

While generally now attributed to Mary Frye, the hugely popular bereavement poem 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep' (often shown as 'Don't Stand at My Grave and Weep) has uncertain history and origins. Debate surrounds the definitive and original wording of this remarkable verse, and for many the authorship is unresolved too. The best evidence and research (summarised below) indicates that Mary Frye is the author of the earliest version, and that she wrote it in 1932. However, many different variations of the poem can now be found, and many different claims of authorship have been made, and continue to be made.

I am especially keen to know of any sightings (especially photographic evidence) of the poem on old gravestones/tombstones. A number of people have contacted me with their recollections of having seen the poem on very old tombstones (perhaps even dated before 1932, notably and most specifically in Texarkana Texas; and Provincetown, Massachusetts) but despite my best efforts to research this (from the UK) I have as yet been unable to substantiate these sightings. If you can help or have similar sightings/recollections please tell me.

To the right is the earliest evidence of the poem's existence that I have seen. I am grateful to P Smith for sending it to me and also for helping me with related information (end 2012-early 2013). The extract right is taken from (page 62) of a memorial service document for the United Spanish War Veterans service held at Portland USA, on 11 September 1938 (the '40th Encampment') published by the US Congress in early 1939. The text is: Do not stand at my grave and weep, The text contains a few slight variations compared with the other versions featured in this article. See the common versions of the Do not Stand at My grave and Weep poem. There is no attribution of authorship in the United Spanish War Veterans memorial service document. The document is nevertheless highly significant, being the earliest (that I am aware of) published version of the poem Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep. The poem in the memorial document is not titled, which is consistent with many other 'official' and historical renderings of the poem, but it contains only eleven lines, not twelve, omitting the line "I am the soft stars that shine at night," (or similar equivalent) which appears in many other 'official' versions, including the famous 'Schwarzkopf printed card version', and the Portsmouth Herald version below. As you will see below Mary Frye asserted that her original poem contained fourteen lines. If you had not yet realised, this is not a simple matter. If you have anything earlier than 1938 please send it. |  |

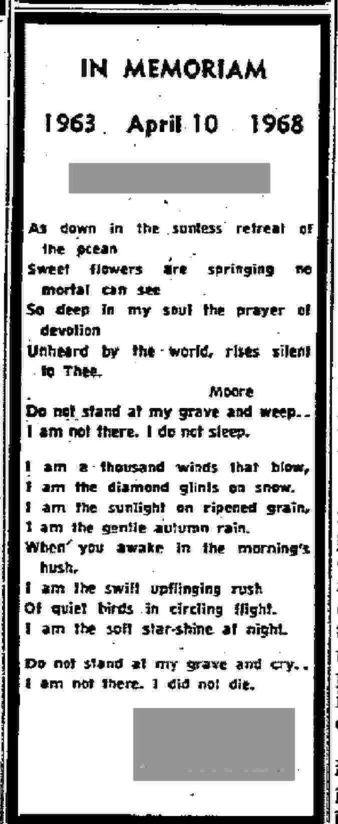

To the right, is the next-oldest published version of the poem (that I am aware of). This private memorial item appeared in the Portsmouth Herald newspaper, New Hampshire USA, on 10 April 1968. The cutting is taken from a PDF (thanks S Watkins) of the full page of the newspaper, on page 3 towards the foot of the second column. I obscured the names for reasons of sensitivity. Obviously this evidence, along with the 1938 publication above, provides a serious challenge to all claims of authorship made in more recent times, of which there have been very many indeed. A clearer reproduction of this 'Portsmouth Herald 1968' version appears below. Notice the variations in wording compared with the more common versions of the Do not Stand at My grave and Weep poem. The poem is unattributed in the Portsmouth Herald version of 1968, which suggests strongly that the author was unknown by the people placing the item, given that they provide the Moore attribution for the verse above the 'Do Not Stand...' poem. I am keen to receive any information and recollections about the poem's existence, particularly 1960s or earlier. If you have any, especially with written or printed evidence (newspaper cuttings, poetry books, etc), please get in touch. I am also keen to hear from anyone who has corroborated or investigated the research of Abigail Van Buren (aka Jeanne Phillips), the 'Dear Abby' newspaper columnist, or that of Kelly Ryan for Canada's CBC Radio, which was crucial in recognizing the Mary Frye attribution. The many variations and disputed origins have occurred mainly because the poem was never formally published or copyrighted. The poem's interpretation, reproduction, distribution and popularity were therefore able to grow organically, outside of usual publisher controls. 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep' evolved more like folklore or legend - passed from person to person - initially on scraps of paper, hand-written notes, and photocopies - and more recently the poem has spread far and wide by the ease and viral nature of internet publishing. If clear different and reliable evidence of origin other than Mary Frye's claim were to be produced then I will gladly publish the evidence to clarify the matter. Meanwhile the best available evidence suggests that Mary Frye wrote the 'original' or earliest version of Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep', from which the many variations subsequently evolved, and this page reflects that situation. In an effort to further clarify the origins of the 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep' poem I am keen to find the earliest evidence of the poem's existence - particularly if any exists before 1938 - and I ask anyone who can help with this please to contact me. So, please contact me with your earliest recollection or evidence of the poem Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep. |  |

I am aware of a claim that the poem was published and attributed to Mary Frye in a 1944 edition of the American 'Ideals' magazine. I contacted Ideals magazine (now owned by Ideals Books, now part of Guideposts, Retail Products LLC) in July 2009 and received a very helpful reaction, to which end they were unable to find the poem in their records or archived magazine copies, and specifically not in the 1944 Christmas Ideals edition, which incidentally was the very first Ideals edition. The Ideals company has been through several ownerships over the years so its records are not entirely complete, which prevents a wholly reliable conclusion to this line of inquiry. That said, according to Ideals, the poem did not appear in the 1944 edition as claimed. I have tried to contact the claimant for more details and clarification to no avail.

There have been scores of different claims of authorship of this poem. Various attributions are replicated on the web, which for obvious reasons may not be reliable, despite some appearing very widely, such as the attribution to Melinda Sue Pacho, and also to Emily Dickenson. In the case of Emily Dickenson, since she was a published poet of considerable reputation (enabling the matter to be thoroughly researched), we can be sure that this attribution is entirely wrong. Emily Dickenson did not write Do Not Stand at my Grave and Weep. However where attributions involve less well known people, evidence either way is virtually impossible to find. In the case of Melinda Sue Pacho, there seems no evidence of who she was, where and when she lived, or anything else about her, and until any emerges, there is naturally no evidence for the attribution. Please let me know if you have any information about Melinda Sue Pacho.

I am open to suggestions and corrections about any of this, and any other aspect of the Do Not Stand at my Grave and Weep poem and its origins.

origins background

The following is based on the Mary Frye claim and the research which is now generally regarded to have substantiated it.

This information is based on the generally accepted evidence indicating Mary Frye to be the author of Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep. While aspects of the Mary Frye claims and research are not wholly convincing, without evidence to the contrary the Frye attribution is the best there is. If I am presented with different more reliable evidence then I will be happy to publish it.

Originally the verse had no title, so the poem's first line, 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep' naturally became the title by which the poem came to be known. As already explained, the title is commonly shown as 'Don't Stand at My Grave and Weep'. The poem can be found with different titles however, notably 'I Am', reflecting the repetition of that phrase in the verse. The variations which occur in the poem reflect the organic way that the poem spread.

Crucial in establishing and publicizing the Mary Frye attribution were the research, interviews and radio broadcast by Ms Kelly Ryan, on the Canadian CBC Radio show, Ideas; the edition called A Poetic Jouney, broadcast on 10 May 2000.

Mary Elizabeth Frye (1905-2004) was a housewife from Baltimore USA. When a friend's mother died this apparently prompted Mary Frye to compose the verse, which in various forms has for decades now touched and comforted many thousands of people, especially at times of loss and bereavement.

According to the Kelly Ryan interview Mary's friend was a German Jewish woman (some reports say young girl) called Margaret Schwarzkopf. Mary Frye said that Margaret was her closest friend and felt unable to visit her dying mother in Germany due to the anti-Semitic feeling at home. This led to Margaret Schwarzkopf's tearful comment to Mary Frye, after a shopping trip, to say that she had been denied the chance to "... stand at my mother's grave and say goodbye". This prompt caused Mary Frye to write the verse there and then on a piece of paper torn from a brown paper shopping bag, on her kitchen table, while her distressed friend was upstairs. Mary Frye said the poem simply 'came to her'.

It's fascinating that the poem came into such widespread use, and this is was helped because it was not subject to the usual restrictions of copyright publishing controls.

It seems, although information is a little hazy about this, that at some time after Margaret Schwarzkopf's mother's death, friends of the Schwarzkopf family enabled or arranged for a postcard or similar card to be printed featuring the poem, and this, with the tendency for the verse to be passed from person to person, created a 'virtual publishing' effect far greater than traditional printed publishing would normally achieve.

This is Kelly Ryan's interpretation of how the poem began to spread, based on her research and interview of Mary Frye:

"The poem's journey began at that kitchen table in Baltimore. Margaret took it to work with her, and gave it to friends there. One had a relative who worked in the Federal Printing Press in Washington. Copies were 'done up' and given away..."

Because of the way the poem in its various versions spread without formal copyright, attribution or controlled publishing, the basic Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep verse has for many years been firmly in the public domain. For many years (and presently still among many people) the poem's origin was generally unknown, being variously attributed to native American Indians (especially Navajo), traditional folklore, and other particular claimant writers. The poem has appeared, and continues to, in slightly different versions, and there are examples also of modern authors adding and interweaving their own new lines and verses within Frye's work, which adds to confusion about the poem's definitive versions and origins.

The Mary Frye claim to Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep seems first to have been publicly pronounced when the poem was was attributed to Mary Frye in 1998 following research by Abigail Van Buren, aka Jeanne Phillips, a widely syndicated American newspaper columnist, whose 'Dear Abby' column apparently communicated directly with Mary Frye concerning original authorship of the poem.

The research findings of Van Buren and her assistants are featured strongly in Kelly Ryan's CBC Radio show 'Poetic Journey' presented by Ms Ryan on 10 May 2000. In the broadcast, Abigail van Buren's daughter Jeanie (or perhaps Jeanne) reads a copy of the letter sent by 'Dear Abby' to Mary Frye agreeing that Mary is the author of the poem, but also adding, strangely, that the letter is not dated. The wording of the letter is strange too. Make of it what you will.

I have listened to a recording of the CBC Radio show and it presents a strong but certainly not bullet-proof argument for the Mary Frye attribution. Kelly Ryan says in the broadcast that she searched for a year to locate the author, prompted by a documentary about the Swissair flight 111 (one-eleven) plane crash. Ms Ryan seems to have great personal interest in the poem and its origins, and seems convinced that Mary Frye is the author. In addition to Mary's own testimony and the Dear Abby confirmation (such as it is), Ms Ryan places much reliance on her interview with British 'retired journalist' Peter Ackroyd (or Ayckroyd - it is pronounced both ways in the broadcast), and his earlier research of the poem. In the broadcast however there is considerable vagueness in the trail that led Peter Ackroyd to locate and identify Mary Frye as the poem's author, not least the the role of the Baltimore local newspaper in confirming Mary Frye to be the author - described as if the newspaper had always known, like, 'what's all the fuss about - doesn't everyone know?...' This is again rather strange. The trail is even less clear when it comes to finding Peter Ackroyd's book about his search for the author, which is mentioned in the broadcast, but seems impossible to locate. Perhaps it was never published: Ms Ryan says "Peter has now written book about his search for the author..." but this does not mean necessarily that it was ever published. The identity of this particular Peter Ackroyd (or Ayckroyd) is not clear either. I received confirmation (from his agent, Jan 2008) that it is not the well-known author and biographer of the same name. If you happen to know the Peter Ackroyd (Ayckroyd?) who featured in the CBC Radio show please contact me.

In October 2002 the eminent pop songwriter Geoff Stephens wrote a very interesting review of Ms Kelly's findings and broadcast, since becoming captivated by the poem and producing his own song version of the poem, re-titled To All My Loved Ones. Unfortunately Geoff Stephens' webpages are no longer available. If I can make arrangements to offer his materials on this website I will do so.

I emphasise again that this is the best evidence that exists for the origins of the Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep poem. Some people dispute these origins, and also the rigour of the research which established them. However until and unless better different evidence appears, the Mary Frye claim is the strongest.

different versions of the poem

According Kelly Ryan's research, implicitly confirmed through Ms Ryan's interview of Mary Frye, this is the version of Frye's poem which featured on the card printed after Mary gave the poem to Margaret Schwarzkopf. The poem was untitled:

(Schwarzkopf printed card version)

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning's hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

(I refer to this version as the 'Schwarzkopf printed card version'. In fact according to the Frye claim the card was printed by the Federal Printing Press, Washington, when it came to their attention via a work colleague of Margaret Schwarzkopf.)

This alternative 'modern definitive version', with slight variation in lines 9 and 10, was featured in Mary Frye's obituary in the British Times newspaper in September 2004, although no source was given other than attribution to Mary Frye:

(do not stand at my grave and weep- modern)

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning's hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft starlight at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

In her interview with Kelly Ryan broadcast on CBC Radio in 2000, Mary Frye confirmed the following interpretation as her original version. The version is quite different to the versions above. Note especially the extra four lines (11-14), and the present tense 'do' in the final line.

(do not stand at my grave and weep- original)

Do not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there, I do not sleep.

I am in a thousand winds that blow,

I am the softly falling snow.

I am the gentle showers of rain,

I am the fields of ripening grain.

I am in the morning hush,

I am in the graceful rush

Of beautiful birds in circling flight,

I am the starshine of the night.

I am in the flowers that bloom,

I am in a quiet room.

I am in the birds that sing,

I am in each lovely thing.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there. I do not die.

(do not stand at my grave and weep - 1968 portsmouth herald version)

Do not stand at my grave and weep..

I am not there. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awake in the morning's hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft star-shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry..

I am not there. I did not die.

Variations in 1968 Portsmouth Herald version compared with the Schwarzkopf printed card version:

Two dots after 'weep'.

Full-stop (period) instead of semi-colon after 'I am not there'.

Full-stop (period) after 'snow'.

'Sunlight' instead of 'sun'.

'Awake' instead of 'awaken'.

'Upflinging' instead of 'uplifting'.

'Soft star-shine at night' instead of 'soft stars that shine at night'.

Two dots after 'cry'.

Full-stop (period) instead of semi-colon after 'I am not there' in final line.

It's anyones guess as to the reasons for these variations.

(do not stand at my grave and weep - United Spanish War Veterans service version - 1938)

The extract right is taken from (page 62) of a memorial service document for the United Spanish War Veterans service held at Portland USA, on 11 September 1938 (the '40th Encampment') published by the US Congress in early 1939. The poem was unattributed, and untitled. The text is:

Do not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there - I do not sleep.

I am the thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints in snow,

I am the sunlight on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

As you awake with morning's hush

I am the swift-up-flinging rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there - I did not die.

Variations in the United Spanish War Veterans service version compared with the Schwarzkopf printed card version:

Eleven lines instead of twelve; omitted line ten: "I am the soft stars that shine at night".

Hyphen instead of semi-colon in line two break.

Sunlight instead of sun, line five.

"As you awake with morning's hush" line seven is different to all other versions, which tend to feature: "When you... in the.."

'Upflinging' instead of 'uplifting' line eight.

Hyphen instead of semi-colon in last line.

Aside from the missing line, there are lots of similarities between the 1938 War Veterans version and the 1968 Portsmouth Herald version. This perhaps suggests that the poem was not widely used in the intervening years (because distortions obviously happen more with wide use). This is supported by the apparent absence of any (known by me) published evidence of the poem between 1938-68.

Accordingly I am particularly keen to see any versions of this poem published between 1938-68. If you have one please send it.

'native american prayer' version popularised and circulated since late 1990s or earlier

Here's another version of Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep, and which seems to have been popularised on the worldwide web, and, as happens with the verse, circulated among friends many thousands of times. Apparently this version (thanks Anne) has existed since the late 1990s, and perhaps earlier.

There are other versions - this is one example - which have emphasised the supposed 'Native American' origins, such is the appeal of that particular very popular but (probably) incorrect attribution.

Native American Prayer

I give you this one thought to keep -

I am with you still - I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am sunlight on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awake in the morning's hush

I am the swift, uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not think of me as gone -

I am with you still - in each new dawn.

(Typically the attribution states 'Author unknown')

Thanks Anne for this version and supporting information.

If you use this version it is probably appropriate to say that it is adapted by person(s) unknown from the original poem Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep, generally attributed to Mary Frye, 1932.

If you know who originated this particular adaptation please tell me so that suitable credit can be given.

From a research perspective this is all rather confusing, but in terms of spiritual and human reaction it's all very powerful and compelling, whichever way you look at it.

Any of the above versions might also be shown instead with the title 'Don't Stand at My Grave and Weep'. It's a matter of personal preference, although the 'Do Not Stand...' version is consistent with the Mary Frye claim and the most common interpretations. The full 'Do Not Stand..." is also arguably more rhythmical and poetically balanced and than the shortened 'Don't Stand...' version.

Since there is no clear 'definitive version', (and even if there were), it's a matter of personal choice as to which one to use, and the choice gets broader with every new poetic adaptation, and every new musical version.

So it is likely that the mystery - as well as the magical appeal - of the verse will continue. Probably the mystery has contributed to the poem's appeal. It is likely also that the poem will forever touch people, in the way that people are touched and inspired by Max Ehrmann's 'Desiderata', and by Rudyard Kipling's 'If'.

'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep' and its timeless appeal provide a wonderful illustration of the power of language, and the power of ideas and concepts to spread far and wide, quite organically. Beautiful words transcend all else; they inspire, console and strengthen the human spirit, quite regardless of who wrote them.

song versions of do not stand at my grave and weep

Several different musical and song interpretations of Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep have been written and published, with different titles, often with variations to the original words.

Another notable recent musical interpretation of Do not Stand at my Grave and Weep is by the Irish female singer songwriter Shaz Oye (pronounced 'Oh Yay'), subtitled 'Requiem', and available as a free download from Shaz Oye's website.

And here is a free MP3 song version of the poem with harp accompaniment by harpist Sue Rothstein.

Katherine Jenkins also recorded a song version of the poem on her 2005 album, Living A Dream.

I am informed (thanks M Straw, R Anderson and A Chittenden) of a Japanese version of the poem which has also been set to music and perfomed as a song, which became a big selling single in Japan in 2006-07, sung by Masafumi Akikawa (also known as Masashi Akiyama and other combinations of the two names seemingly), music composed by Man Shirai. The Japanese version of the poem and song is generally to be called A Thousand Winds, or more fully in Japanese 'Sen No Kaze Ni Natte', meaning 'I Have Become a Thousand Winds'.

Additionally (thanks J M Flaton) British boy's choir Libera have recorded musical versions of the poem, one with piano, the other with harp and strings, music by Robert Prizeman.

A part-spoken, part-choral version of the poem features strongly in the 2005 BBC film The Snow Queen. The film is based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairytale of the same name, and the earlier 2003 musical score by Paul Joyce. Juliet Stevenson (who plays Gerda's mother) narrates the poem, assisted by girl soprano Sydney White and choir. Ironically, given that the context is a fairytale, the usual spiritual meaning of 'I did not die' is given a literal twist in the film; that is to say, the character (the boy Kay) is firstly not dead when initially thought to be (he is merely missing, in thrall of the wicked Snow Queen), and secondly when later he is found actually properly dead, or at least in a reasonably permanent coma on a slab of ice, he is brought back to life by the heroine Gerda's tears. I did say it is a fairytale. The Juliet Stevenson version of the poem is available on the film soundtrack, and can also be heard on the film's website. The Kelly Ryan interview features a choral piece called In Rememberance, from a requiem composed by Eleanor Daley; a chanted song called Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep by Kathy Martin; and Stephen Raskin's Elegy for the Masses - a larger work which is symphonic in size and structure, written in 1995 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - it contains three songs, one of which is titled Do Not Stand At My Grave and Weep. The Kathy Martin spellings are not guaranteed to be correct. If you know better please tell me. Researching most things surrounding this poem is curiously difficult. I am grateful to Stephen Raskin for clarifications about his work.

The Irish 'Ballad of Mairead Farrell' is an adaptation of the poem Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep, notably having been recorded by Irish band Seanchai and the Unity Squad, featuring Rachel Fitzgerald on vocals, and also separately by Cara Dillon.

Geoff Stephens (mentioned above) produced and recorded a song version of Do Not Stand by My Grave and Weep, which he re-titled To All My Loved Ones.

And (again thanks J M Flaton, Jan 2009) here are further suggestions of musical and audio versions, many if not all available from iTunes:

"The actor Samuel West recites the poem, albeit in a rather dry tone; Juliet Stevenson wins that one hand down. Her version and the sung version are on the Snow Queen sound tracks. Jamie Paxton has a folky arrangement on his album 'Remember'; Sue Anne Pinner does it in yet another arrangement on the album 'Illumination'; very new age. Lee Mitchell (in 'The Great War') has made yet another composition for voice and guitar, a bit CSNY/S&G-style (that's Crosby Stills Nash and Young, and Simon and Garfunkel), and it sounds great. The US Army Corps (in 'A Capella and Otherwise') has a close harmony jazzy version. Composer Brian Knowles created yet another version, in a light classical setting sung by Juliette Pochin and the City of Prague Philharmonic (in 'Poetry Serenade') Nyle P Wolfe (in the album 'Moodswings') also has a version, in a sort of Sinatra style. Angel Band ('With Roots and Wings') has made a totally different version in country and western style. Christine Sperry and Jenny Undercofler (in 'Songs, Dances and Duos') perform a sort of Hugo Wolf song version. The British composer Howard Goodall has created 'Eternal Light: A Requiem', in which 'Do not stand...' is included as Part V: Lacrymosa. The song, in a vague William Vaughan setting, is performed by baritone Christopher Maltman with London and Oxford musicians. All in all I counted as many as twelve different versions, including that 'Libera'. Apparently the poem has inspired many composers..." (With grateful ackowledgements to J M Flaton)

attribution, use and copyright of the poem

Given the popularity and poignant nature of Do Not Stand at my Grave and Weep, increasing numbers of people have an interest in using the words for songwriting and/or performance, or for some other usage which in the case of other copyright-protected works would usually warrant permission or licence from the author or rights holder.

In the case of Do Not Stand at my Grave and Weep however such permission is arguably unnecessary, and is actually impossible to obtain, since ownership is not absolutely proven.

For what it's worth, if you are wondering about copyright, usage, permission, attribution, my view is that the 'original' version(s) of the poem (attributed to Mary Frye) are not subject to copyright restriction, because these versions are regarded now to be in the public domain; moreover no author has to date successfully established any copyright control over the 'original' versions of the work and is now probably never likely to do so.

The best available information - and therefore the default attribution statement for most people, until and unless better evidence is found - is that the ('original' Mary Frye) words of Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep are 'attributed to Mary E Frye, 1932'.

There are several musical versions already published - some via large reputable publishers. Useful clues and guidance as to appropriate attribution might be found by looking at how other publishers have attributed the work in their track-listings and publishing notes.

Be aware that many people have added new words to the 'original' Frye version(s) of the poem, which will in some cases be subject to copyright and potential liability if used without permission or licence. It is possible even that certain people have written extensions or adaptations of the 'original' public domain work chiefly or partly with such a motive (of deriving gain from others' use of the new part of the work), so caution is recommended in using any material, especially significantly and commercially, which falls outside of what could be deemed public domain content.

N.B. I am not referring here to single readings at funerals or related use, which has occurred widely and completely lawfully for many years, with or without attribution. I refer to copyright and attribution implications for commercial publishing, in which regard you must make your own decisions, ideally after doing your own research and if necessary seeking your own local qualified advice. These notes are for guidance only and carry no acceptance of any liability whatsoever.

possible influences

Whatever is the authorship and/or evolution of the poem Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep, its universal appeal is undeniable.

Yet the question of the poem's authorship and evolution into its modern versions is as intriguing as its vast appeal.

By virtue of its massive popularity, and irrespective of highbrow critical assessment, the poem contains a quality which makes it accessible and deeply meaningful to people all around the world. Analysing this quality is very difficult. People relate to the poem instinctively - it touches human reactions at an unconscious level. People love the poem without necessarily knowing why or how.

According to Mary Frye's recollections she took just a few minutes to write the poem; moreover she worked purely from instinct - she did not regard herself as a writer or poet in even the remotest sense. While it is remarkable for such a fabulously popular work to have been created in this way, this is not to say that such an inspirational flash automatically warrants suspicion. Creativity is mysterious. Significant artistic works can certainly come from moments of inspiration, rather than years of study and toil.

The possibility that the poem somehow evolved into its current form, with or without Mary Frye's original input, is just as amazing, nevertheless this sort of organic evolution seems to have been responsible for the poem's modern variation (from Mary Frye's claimed original version), represented by the first two versions above.

This instinctive aspect of language is fascinating, and I am open to ideas about why the poem works so well on an instinctive level.

Perhaps a factor is the repeating use of the 'I am' statements, which resonate with well known biblical statements, notably some attributed by John to Jesus (I am the bread..., I am the light..., I am the way..., I am the true vine..., etc).

Perhaps we are genetically or otherwise conditioned to respond the structure of the poem.

Let me know if you can add to this appreciation.

For example, you might find the following observations interesting:

From J McKeon, Sep 2008:

I was struck by the similarity, in metric form, of Mary Frye's poem and an ancient Irish Gaelic poem 'The Song of Amergin'. The metric form is of seven rhyming couplets of 'I am' statements, followed by an eighth expanded couplet. The rhymes are present in the original Gaelic, but absent in the translation. Amergin was a bard, and the lines are a mystery, in that they have hidden meanings which convey a message. I am not suggesting that Frye copied this poem, just that she may have been inspired to produce her poem in the same image. This is an extract of the translation into English by Robert Graves, from his book 'The White Goddess':

Robert Graves' translation is commonly known as The Song of Amergin.

Extract (full versions below):

I am a stag of seven tines,

I am a wide flood on a plain,

I am a wind on the deep waters,

I am a shining tear of the sun,

I am a hawk on a cliff,

I am fair among flowers...

(Robert Graves' translation of The Song of Amergin was first published in his book The White Goddess of 1948. The original work is from ancient Gaelic mythology. Thanks John McKeon, County Limerick, Ireland.)

Incidentally a 'tine', mentioned in the first line, is an antler, or, Graves speculates, seven tines might refer specifically to seven points on an antler.

N.B. If Mary Frye wrote the Do not Stand poem in 1932 this obviously predates Graves' translation above, but it most certainly does not predate the use of the 'I am...' themes which feature in both works.

The structure of the poem and the 'I am...' themes can be traced back at least a thousand years, and arguably a few thousand years, which perhaps influenced the way Do not Stand was written and/or the way interpretations have evolved, and certainly the way we respond to it today.

the song of amergin

Robert Graves provided several different interpretations of the Song of Amergin, partly because "...Unfortunately the version which survives is only a translation into colloquial Irish from Old Goidelic..", and partly because of the calendar symbolism within the poem, to which Graves applied considerable analysis. Here are the main Graves interpretations, within which you will see several themes closely matching the ones found in Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep:

Graves explained that the Song of Amergin is also known as the Song of Amorgen, and that the poem is "...said to have been chanted by the chief bard of the Milesian invaders, as he set foot on the soil of Ireland, in the year of the world 2736 (1268BC)..."

Graves also refers to the observations of historian, Dr R S Macalister, that the same piece (i.e., the Song of Amergin) is 'in garbled form' put into the mouth of the Child-bard Taliesin in telling of his transformational prior existence. This gives rise to a further variation of Graves interpretation of the poem.

Incidentally the Milesians were, according to Irish mythology, the last invaders of Ireland, arriving in Ireland in the 1st or 2nd century BC, descended from Mil Espaine or Milesius, meaning 'soldier of Hispania', because that's what he was. Hispania equates to the Spanish/Portuguese peninsula territory of the Roman Empire. Milesius was said have dreamed that his descendents would colonise Ireland, and legend tells that some of his sons did so. Goidelic equates to Gaelic in referring to the family of languages including Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx (Isle of Man). Taliesin (also known as Taliessin) was a Welsh poet of the 6th century, who according to legend entertained Celtic Kings of the time, including King Arthur. Taliesin used the Brythonic language, an old native British language family including Breton, Cornish and Welsh of that period. The Celtic language families Goidelic/Gaelic and Brythonic predated the imported Germanic and French-based languages, and therefore feature significantly in old British legend and poetry such as the Song of Amergin. Robert Graves specialised in interpreting and translating this sort of very old British poetry, and if that interests you then you'd probably find his book The White Goddess very enjoyable.

The first of Graves' translated versions of the poem is shown below with Graves' accompanying notes.

Of enormous significance, in my view, is the age of the Song of Amergin. The poem is translated from folklore dating back at least a thousand years, and the meanings and style of the poem can be linked closely with ancient Irish civilisation pre-dating the Bible, the Egyptian pyramids and Stonehenge. In this respect, the Song of Amergin is perhaps the earliest meaningful example of the use of the 'I am...' imagery which we can connect to the poetic technique found in 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep'.

the song of amergin (literal translation - Graves)

| God speaks and says: | Gloss [Graves uses 'gloss' to refer to the meaning of each line.] |

| I am a wind of the sea, | for depth |

| I am a wave of the sea, | for weight |

| I am an ox of seven fights, (or) I am a stag of seven tines, | for strength |

| I am a griffon on a cliff, (or) I am a hawk on a cliff, | for deftness |

| I am a tear of the sun, | a dew-drop - for clearness |

| I am fair among flowers, | [no note] |

| I am a boar, | for valour |

| I am a salmon in a pool, | 'the pools of knowledge' |

| I am a lake on a a plain, | for extent |

| I am a hill of poetry, | 'and knowledge' |

| I am a battle-waging spear, | [no note] |

| I am a god who forms fire for a head. | (i.e. 'gives inspiration': Macalister) |

| or I am a god who forms sacred fire for a head. | |

| * * * | |

| 1. Who makes clear the ruggedness of the mountains? | 'Who but myself will resolve every question?' |

| or Who but myself knows the assemblies of the dolmen-house on the mountain of Slieve Mis? | |

| 2. Who but myself knows where the sun shall set? | |

| 3. Who fortells the ages of the moon? | |

| 4. Who brings the cattle from the House of Tethra and segragates them? | (i.e. 'the fish, Macalister, i.e. 'the stars', MacNeill) |

| 5. On whom do the cattle of Thethra smile? | |

| or For whom but me will the fish of the laughing ocean be making welcome? | |

| 6. Who shapes weapons from hill to hill? | 'wave to wave, letter to letter, point to point' |

| * * * | |

| Invoke, People of the Sea, invoke the poet, that he may compose a spell for you. | |

| For I, the Druid, who set out letters in Ogham, | |

| I, who part combatants, | |

| I will approach the rath of the Sidhe to seek a cunning poet that together we may concoct incantations. | |

| I am the wind of the sea. |

© Robert Graves Copyright Trust, 1948, 1952, 1997.

The above is the full and relatively literal translation by Robert Graves of the ancient Irish folklore poem, the Song of Amergin. It is reproduced here including Graves' poem line notes, from The White Goddess (1948, by Robert Graves, edited by Grevel Lindop), under licensed permission from A P Watt Ltd on behalf of the Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust. Publication of the Song of Amergin is not allowed without permission from A P Watt Ltd.

additional notes for the song of amergin version above

These notes are interesting in their own right, but additionally some of what follows provides clues as to how certain words, language and imagery can give rise to powerful human responses, such as occurs in relation to 'Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep', as if at an instinctive, primeval or even genetic level.

Thethra (according to ancient Briton/Celtic folklore), Graves explained was "...the king of the undersea land from which the People of the Sea were supposed to have originated."

The Sidhe are (at time of Grave's writing) regarded as fairies, but in early Irish poetry were a 'highly cultured and dwindling' nation of warriors and poets living in raths (hill forts), notably New Grange on the Boyne. Graves alludes to parallels between the Sidhe warriors and other mythical tribes. The Sidhe apparently had blue eyes, long curly yellow hair, and pale faces, tattoos, carried white shields, and were sexually promiscous but 'without blame or shame'. Seemingly, Graves informs us, the Mosynoechians ('wooden-castle-dwellers') of the Black Sea coast were also tattooed, carried white shields, and 'performed the sex act in public', presumably also 'without blame or shame'. It was a man's world back then for sure.

For me, the comparison between the Irish Sidhe and the Mosynoechians of the Black Sea coast helps the appreciation that the significant meaning of mythological and spiritual imagery is fundamental in human existence - then as now - and somehow might be inherited genetically, aside from through the spoken and written word.

The ancient history of the Boyne makes the 1690 Battle of the Boyne seem comparatively very recent. Boyne is in the county of Meath, north of Dublin, on the north-east coast of Ireland. Boyne is the site of Brú na Bóinne, also known as Brugh na Bóinne, meaning 'palace or dwelling place of the Boyne'. Brú na Bóinne is a settlement and ceremonial area more than 5,000 years old, which to put in perspective existed at least 3,000 years before the baby Jesus was an an eye in God's twinkle, if you will forgive the blasphemy.

Slieve Mis is a mountain range in Kerry. In Irish - Sliabh Mish - is named after a mythological Celtic princess noted for her cruelty.

A 'tine' is an antler. Graves suggests that seven tines might refer to seven points on an antler, on the basis that a stag having six or more points on each antler and being at least seven years old, was regarded as a 'royal stag', although he does not explain further the meaning of a 'royal stag'.

More interestingly, Graves then explains that the poem in its original form (or as close to the original form as Graves was able to determine) would most likely have been 'pied' - that is to say, its 'esoteric' (subtle, purist) meaning would have been disguised. In other words, the meaning was intentionally made difficult to decipher, 'for reasons of security'.

The weaving of hidden meanings into poetry is widely practised, although in more modern times this is for artistic or sensual or subliminal appreciation purposes. Graves suggests that the hidden meanings in the old Celtic poetry, of which the Song of Amergin is an example, held more strategic, perhaps even sinister, implications: as if the poetry were an instrument of leadership or control, and its hidden meanings empowered the chosen few who knew the code.

Graves decoded the Song of Amergin as follows, rearranging the statements of the first main verse according to the thirteen-month calendar and his ideas about the Druid system of lettering, which (for reasons too complex to explain here) linked trees with letters and months of the year:

the song of amergin (transitionary rearranged version - Graves)

Graves says, "There can be little doubt as to the appropriateness of this arrangement..." on which basis we might regard this to be Graves' definitive version.

| God speaks and says: | Trees of the month | |||

| I am a stag of seven tines, (or) I am an ox of seven fights, | B | Dec 24-Jan 20 | Birch | Beth |

| I am a wide flood on a plain, | L | Jan 21-Feb 17 | Quick-beam (Rowan) | Luis |

| I am a wind on the deep waters, | N | Feb 18-Mar 17 | Ash | Nion |

| I am a shining tear of the sun, | F | Mar 18-Apr 14 | Alder | Fearn |

| I am a hawk on a cliff, | S | Apr 15- May 12 | Willow | Saille |

| I am fair among flowers, | H | May 13-June 9 | Hawthorn | Uath |

| I am a god who sets the head afire with smoke, | D | June 10-Jul 7 | Oak | Duir |

| I am a battle-waging spear, | T | Jul 8-Aug 4 | Holly | Tinne |

| I am a salmon in a pool, | C | Aug 5-Sep 1 | Hazel | Colle |

| I am a hill of poetry, | M | Sep 2- Sep 29 | Vine | Muin |

| I am a ruthless boar, | G | Sep 30-Oct 27 | Ivy | Gort |

| I am a threatening noise, | NG | Oct 28-Nov 24 | Reed | Ngetal |

| I am a wave of the sea, | R | Nov 25-Dec 22 | Elder | Ruis |

| Who but I knows the secrets of the unhewen dolmen? | Dec 23 | |||

© Robert Graves Copyright Trust, 1948, 1952, 1997. Reproduced from The White Goddess (1948, by Robert Graves, edited by Grevel Lindop), under licensed permission from A P Watt Ltd on behalf of the Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust. Publication of the Song of Amergin is not allowed without permission from A P Watt Ltd.

the song of amergin (popular modernised version - Graves)

Graves says that the poem can be expanded as follows, according to further analysis and overlay of the alphabetical coding within the writings.

| God speaks and says: | ||

| I am a stag of seven tines, | ||

| Over the flooded world, | ||

| I am borne by the wind, | ||

| I descend in tears like dew, I lie glittering. | ||

| I fly aloft like a griffon to my nest on the cliff, | ||

| I bloom among the loveliest flowers, | ||

| I am both the oak and the lightning that blasts it, | ||

| I embolden the spearsman, | ||

| I teach the councillors their wisdom, | ||

| I inspire the poets, | ||

| I rove the hills like a conquering boar, | ||

| I roar like the winter sea, | ||

| I return like the receding wave, | ||

| Who but I can unfold the secrets of the unhewen dolmen? | ||

| I am the womb of every holt, | A | Graves suggested this five-line pendant, |

| I am the blaze on every hill, | O | which features in copies of the work. |

| I am the queen of every hive, | U | |

| I am the shield to every head, | E | |

| I am the tomb to every hope. | I |

© Robert Graves Copyright Trust, 1948, 1952, 1997. Reproduced from The White Goddess (1948, by Robert Graves, edited by Grevel Lindop), under licensed permission from A P Watt Ltd on behalf of the Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust. Publication of the Song of Amergin is not allowed without permission from A P Watt Ltd.

| Central to Graves rationale is the dolmen arch, which in ancient Irish history was symbolic of the seasons, the calendar, letters linked with trees, and at least one legendary journey of lovers who bedded each night beside a fresh dolmen. The 'alphabet' dolmen arch was arranged thus, says Graves, the posts representing Spring and Autumn, the lintel Summer and the threshold New Year's Day. Don't ask me what happened to Winter. It's extremely complicated, and if you want to explore it further I recommend you get the White Goddess book. |

|

Personally I find the connections fascinating between the symbolism of the Song of Amergin and the bereavement poem Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep.

I can't explain exactly why and how these connections operate, nor even if they actually exist, but intuitively I find them irresistible, in terms of the language, the imagery, the rhythm, and the deep symbolism of fundamental life forces.

As ever I welcome comments and development of these ideas from people far cleverer than me.

christina rossetti - the poems 'remember' and 'song'

English poet Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830-1894) was born into a successful Italian literary family, and Rossetti's work - while initially considered by many to be simplistic and sentimental - is now deemed among the finest writing of English female poets.

Rossetti's father, a refugee from Naples, and her three siblings, were all successful writers. Her mother was from the literary Polidori family, and sister to John Polidori, Lord Byron's friend, and author of The Vampyre, a story with seminal influence on the development of the vampire genre.

Christina Rossetti focused on more homely and heartwarming work, including writings for children. Much of her work has a strong musical quality. The Christmas carol In The Bleak Midwinter is a Christina Rossetti poem. She was also deeply influenced by religion, and wrote a lot about death and dying, typically alluding to nature, and rationalising feelings of departure with continuity.

Christina Rossetti's poem Remember (also known as Remember Me When I Am Gone) contains similar inspirational thoughts alongside Do Not Stand at my Grave and Weep. So does her poem called Song (When I am dead, my dearest) - Rossetti wrote other poems called Song, hence the sub-title differentiation.

Remember and Song were published in 1862, in a collection of works called Goblin Market and Other Poems.

Here is Rossetti's poem Remember. I am grateful to Brian for pointing me to this, especially the last two lines of Remember, which offer an early expression of the core sentiment within Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep.

remember

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more day by day

You tell me of our future that you planned:

Only remember me; you understand

It will be late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget me for a while

And afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and corruption leave

A vestige of the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should forget and smile

Than that you should remember and be sad.

(1862, Christina Rossetti, 1830-1894, English poet)

Rossetti's poem, Song (When I am dead, my dearest), published in 1862, offers further similarities and inspiration:

song (when I am dead, my dearest)

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

(1862, Christina Rossetti, 1830-1894, English poet)

I welcome suggestions of other poems and works which contain earlier expressions, themes, inspiration and comfort, etc., aligned with those found in Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep.

see also

- Elisabeth Kubler-Ross - Five Stages of Grief

- Rudyard Kipling's Poem, 'If'

- Cherie Carter-Scott

- Stephen Covey

- Don Miguel Ruiz

- Desiderata

- Inspirational Quotes

authorship/referencing

© Song of Amergin is copyright Robert Graves Copyright Trust, 1948, 1952, 1997. The above versions of the Song of Amergin are reproduced here including Graves' poem line notes, from The White Goddess (1948, by Robert Graves, edited by Grevel Lindop), under licensed permission from A P Watt Ltd on behalf of the Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust. Publication of the Song of Amergin is not allowed without permission from A P Watt Ltd.

© Cutting from Portsmouth Herald is uncertain copyright, arguably now belonging to Seacoast Media Group, owned by Ottaway, part of Dow Jones & Co (as at 2008).

© Extract from the 1938 Spanish War Veterans Memorial Service, Portland, USA, published 1939, was, and presumably remains, copyright of the US Congress, or relevant publisher nowadays owning such rights.

© Alan Chapman 2005-2013, aside from the Song of Amergin (see above) and the original Do not Stand at My Grave and Weep poetry which is generally attributed to Mary Frye, 1932. Please retain this notice on all copies.