What Is Reflective Practice?

Reflective Practice is a modern term, and an evolving framework, for an ancient method of self-improvement.

Essentially Reflective Practice is a method of assessing our own thoughts and actions, for the purpose of personal learning and development.

For many people this is a natural and instinctive activity.

We can use Reflective Practice for our own development and/or to help others develop.

Reflective Practice is a very adaptable process. It is a set of ideas that can be used alongside many other concepts for training, learning, personal development, and self-improvement.

For example, Reflective Practice is highly relevant and helpful towards Continuous Professional Development (CPD). It's also very helpful in teaching and developing young people and children.

Reflective Practice is mainly concerned with self-development. It enables:

- Future personal growth, and addresses:

- How we think and feel about ourselves and situations in the present, and

- How we think and feel about ourselves and situations in the past.

As such, Reflective Practice is a valuable methodology for using insights and learning from our past to:

- Assess where we are now

- Improve our present and future

This offers benefits far beyond professional learning and development, for example extending to, and not limited to:

- Human relationships - workplace, romance, parenting, etc

- Rehabilitation

- Reconciliation

- Mediation

- Stress-reduction and management

- All sorts of teaching, training, coaching, counselling, etc

- Parenting

- Coping with change and trauma

Reflective Practice is essentially a very old and flexible concept, so it might be called other things.

This alternative terminology, which includes some familiar words, can help us to understand and explain its principles and scope.

For example, Reflective Practice might also be called, and is synonymous with or similar to:

- Personal reflection

- Self-review

- Self-awareness

- Self-criticism or self-critique

- Self-appraisal

- Self-assessment

- Intra-personal awareness

- Personal cognisance/cognizance

- Reflective dialogue

- Critical evaluation

- Self-analysis of our thoughts, feelings, actions, performance, etc

Increasingly these principles, terminology, and underpinning theory are defined and conveyed within the term 'Reflective Practice' and its supporting framework of terminology and application.

As such, 'Reflective Practice' is a theory by which modern and traditional self-improvement ideas can be more clearly defined, refined, expanded, adapted, taught, adopted and applied, for the purposes of personal development, teaching and coaching, and wider organizational improvement.

Reflective Practice is also helpful for personal fulfilment (US-English fulfillment) and happiness, in the sense that we can see and understand ourselves more objectively.

Reflective Practice enables clearer thinking, and reduces our tendencies towards emotional bias.

So we are considering a fundamental human concept.

Incidentally, the term 'Reflective Practice' is generally shown here with capitalized initial letters. This is for clarity and style - the term can be shown equally correctly as 'reflective practice', or 'Reflective practice'.

The capitalization also differentiates the term Reflective Practice from other general uses of the word 'practice' in referring to a person's work or practical things, which are clarified as such throughout this article.

The alternative spelling of 'practise' is not used here because traditionally this spelling refers to the verb form of the word, whereas Reflective Practice is a noun, (just as 'advice' is a noun and 'advise' is a verb).

Let's look now at some formal and technical definitions of Reflective Practice.

I am grateful to Linda Lawrence-Wilkes, an expert in Reflective Practice, for collaborating and contributing to the technical content of this free Reflective Practice reference guide, and related Reflective Practice self-assessment instruments. See Linda's biography and contact details.

Definitions and Related Terms

As with any theoretical concept, definitions of Reflective Practice convey a basic technical description of the subject.

Definitions alone do not fully explain how and why something operates, nor teach us how to use it.

Definitions do however provide a useful basis for comprehension, and consistent terminology for discussion, especially for a subject open to quite different interpretations.

Definitions also help establish firm meanings, for sharing ideas, adopting the methods, and understanding of how Reflective Practice can be used, alongside other developmental methodologies.

Reflective Practice is an ancient concept. Over 2,500 years ago the ancient Greeks practised 'reflection' as a form of contemplation in search of truth, and this ancient meaning of reflection features in several modern definitions. There are references also to the power of reflective learning in the writings attributed to ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius, around 460BC.

The following various definitions convey their own distinct meanings, and also assist the reader in developing a quick general appreciation of Reflective Practice as a whole. The definitions are not in alphabetical order - they are ordered more in a historical sense, roughly according to the evolution of the terminology/concepts concerned.

Reflection

"Careful thought or consideration.." Wiktionary, 2015.

"Serious thought or consideration..." Oxford English Dictionary, 2006.

"Quiet thought or contemplation..." Collins Free Dictionary, 2003.

"The action of turning (back) or fixing the thoughts on some subject; meditation, deep or serious consideration... (and philosophically) the mode, operation or faculty by which the mind has knowledge of itself and its operations, or by which it deals with the ideas received from sensation and perception..." Oxford English Dictionary, 1922.

"...A mental process of thinking about what we have done, learned and experienced..." Professor Jenny Moon, teaching expert and author, 1999.

Reflect - "Turn one's thoughts back on, meditate on, ponder.." Chambers Etymology, 2000

Human self-reflection - "...the capacity of humans to exercise introspection and the willingness to learn more about their fundamental nature, purpose and essence. The earliest historical records demonstrate the great interest which humanity has had in itself. Human self-reflection invariably leads to inquiry into the human condition and the essence of humankind as a whole. Human self-reflection is related to the philosophy of consciousness, the topic of awareness, consciousness in general and the philosophy of mind..." Wikipedia, 2015.

Reflective Practice - "...the capacity to reflect on action so as to engage in a process of continuous learning..." (Schon 1983:102-104), and "...paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice [life/work experiences] reflectively and reflexively. This leads to developmental insight..." (Bolton 2010:xix) Wikipedia, 2015.

Reflexivity - "Finding a way to stand outside ourselves to get a more objective view of ourselves..." Kitchener, 1983

Critical self-reflection - "To know how and to what extent it might be possible to think differently, rather than legitimating what is already known … a test of the limits that we may go beyond" Michel Foucault, 1992.

Critical Reflection - "The [Brookfield] 'Lens theory' suggests that apart from reflecting on our own personal beliefs, we reflect through other 'lenses', on multiple perspectives including theory..." Brookfield, 1995.

Reflector, critical reflector, non-reflector - Terms derived from the above, referring to people and the type/extent of reflection they use. For example 'the reflector' refers to a person who uses reflection of some sort. A 'critical reflector' more specifically refers to someone who uses Reflective Practice as a learning tool to question and evaluate themselves, others and situations. A 'non-reflector' is a person who rarely or never uses reflection. The terms are used commonly in academic or technical writing, when describing or reporting on reflective methods and activities.

Metacognition

"...To monitor our own learning progress to become aware of the limits of our own knowledge and values, assumptions and expectations (frames of reference)..." Kitchener, 1983.

"Knowing about knowing" and "Cognition about cognition." Traditional informal definitions, Wikipedia 2015

"Awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes." OED, 2006.

"... Metacognition can take many forms; it includes knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving. There are generally two components of metacognition: knowledge about cognition, and regulation of cognition... This higher-level cognition was given the label metacognition by American developmental psychologist John Flavell (1979). The term metacognition literally means cognition about cognition, or more informally, thinking about thinking. Flavell defined metacognition as knowledge about cognition and control of cognition. For example, I am engaging in metacognition if I notice that I am having more trouble learning A than B; or if it strikes me that I should double-check C before accepting it as fact,.. (JH Flavell 1976, p232)..." Wikipedia, 2015.

Metacognition is a particularly important aspect of modern Reflective Practice. There is a broad correlation between metacognition (being aware of one's own thinking) and conscious competence (being aware of one's own capability) - because, for example, we can't go beyond our limits until we know what our limits are.

Transformative learning "...Incorporating the examination of assumptions, to share ideas for insight, and to take action on individual and collective reflection..." Jack Mezirow, 2000.

Here are four additional definitions of fundamental terms within/relating to Reflective Practice, according to Linda Lawrence-Wilkes, 2015:

Reflection - Engagement in a deliberate mental process of thinking about, or contemplating, things that have happened, what was experienced and learned, from our own and from others' points of view. Reflection here means looking beneath the surface to find the truth about something, to draw conclusions for building new knowledge.

Reflexivity - Reflexivity is the process of 'stepping back' from a situation we are involved in, for a 'helicopter view' of ourselves. Here we examine ourselves to gauge our values, assumptions, behaviour and relationships, and thereby monitor our learning and develop our intra-personal and inter-personal skills (equating to self-management, and external relationships).

Critical Reflection - Critical Reflection is the adoption of a questioning stance to solve problems, challenge the 'status quo' and examine our own assumptions. This extends to consideration of wider socio-political perspectives and other relevant diverse contexts, theory and professional activity.

Reflective Practice - Reflective Practice is the use of self-analysis to understand, evaluate and interpret events and experiences in which we are involved. This extends to being able to form a theoretical view or analysis, as would allow clear explanation to others, if required. The process of Reflective Practice seeks to enable insights and aid learning for new personal understanding, knowledge, and action, to enhance our self-development and our professional performance.

Here's a much simplified presentation of the above, to show the main differences between these terms/definitions more clearly:

| Reflection | Reflexivity | Critical Reflection | Reflective Practice |

| Thinking about and interpreting life experiences, beliefs or knowledge. | Thinking objectively about ourselves, our behaviour, values and assumptions. | Broad contemplation to question and examine knowledge, beliefs and actions for change. | Use of reflective methods for personal and professional growth. |

Please note that the table above is an extremely concise summary, and is therefore very much open to debate. Consider it as a quick aid to appreciating the different meanings. There could be many other interpretations. If you've a good one please send it.

History of Reflective Practice

We have already seen that terms such as reflection and critical thinking can mean different things to different people, and this variable characteristic features in the founding ideas of Reflective Practice. This variability is likely to persist.

A major feature in the development of Reflective Practice theory is the evolution of:

- Simple reflection (contemplation without necessarily having a purpose)

- Into critical reflection (contemplation with evaluation)

- Into critical thinking or critical reasoning (a balance of reasoning and reflection to assess and develop options and plans)

Reflection is often thought of as contemplation, rather than critical thinking. Modern dictionary definitions support this. Critical thinking is more often aligned with logical reasoning and enquiry.

It's long been observed that different learning methods produce different types of learning. Chinese philosopher Confucius (551-479BC) reportedly theorized: "By three methods we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest." (Confucius, The Analects: ch2, compiled posthumously, c.500BC)

Rooted in Greek philosophy, critical thinking is based on a Socratic idea of a reasoned process of weighing up the evidence to decide whether something is believed to be true or false. (Socratic refers to ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, c.470-399BC.)

Much later, the concept of reflection was taken up in the 18th Century enlightenment movement, a reaction against the turbulent and superstitious (and more oppressive) middle ages.

Here are some of the important historical conceptual interpretations that have helped to shape modern definitions and development of Reflective Practice, and its related concepts. You will see below the increasing sophistication of the ideas, from basic reflection, to critical thinking, to critically Reflective Practice.

Immanuel Kant - German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is considered one of the founders of Western philosophy. Kant wrote the 'Critique of Reason' in 1781, which supported ideas for a scientific logical and rational thinking approach, enabling reasoned thinking, being superior to dogma and other received opinion from authority.

Bertrand Russell - Bertrand Russell (1872-1970, 3rd Earl Russell of Kingston Russell), an English philosopher, mathematician and supporter of Kant's scientific approach, considered that knowledge is 'a belief in agreement with facts'. He asserted that to believe in something with no evidence is inadequate, and instead we should check if there are accurate and agreed supporting facts, and who agreed them (1926).

John Dewey - John Dewey (1859-1952) was an American philosopher and educational reformer. He is seen as the founder of experiential education, linking reflection and action, so as to enable new experience and knowledge. In 1910, he wrote a book for teachers titled 'How We Think', in which he described critical thinking as reflective thought, moving reflection beyond contemplation. Dewey used and defined the term Reflective Thought to mean:

"...Active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief, or supposed form of knowledge, in light of grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends..." (Dewey 1910:6)

Crucially here, reflection is seen as more than impulsive thinking or day-dreaming with no purpose. It is a way of deliberately thinking in a reflective (i.e., deep and interpretative) way about experiences, beliefs or knowledge, to make more careful judgements (US-English, judgments), based on objective grounds.

Thus, reflecting on things that have happened in our lives can open up more options and enable sound reasons for action.

Jean Piaget - Jean Piaget (1896-1980), a Swiss psychologist, proposed the theory that children mature in their thinking through different stages of development. He asserted that experience, concept, reflection and action are the foundation by which adult thought is developed (1969). This suggests that reflection is needed for learning, and connects reflection with action, to underpin critically reflective thinking for new understanding and knowledge.

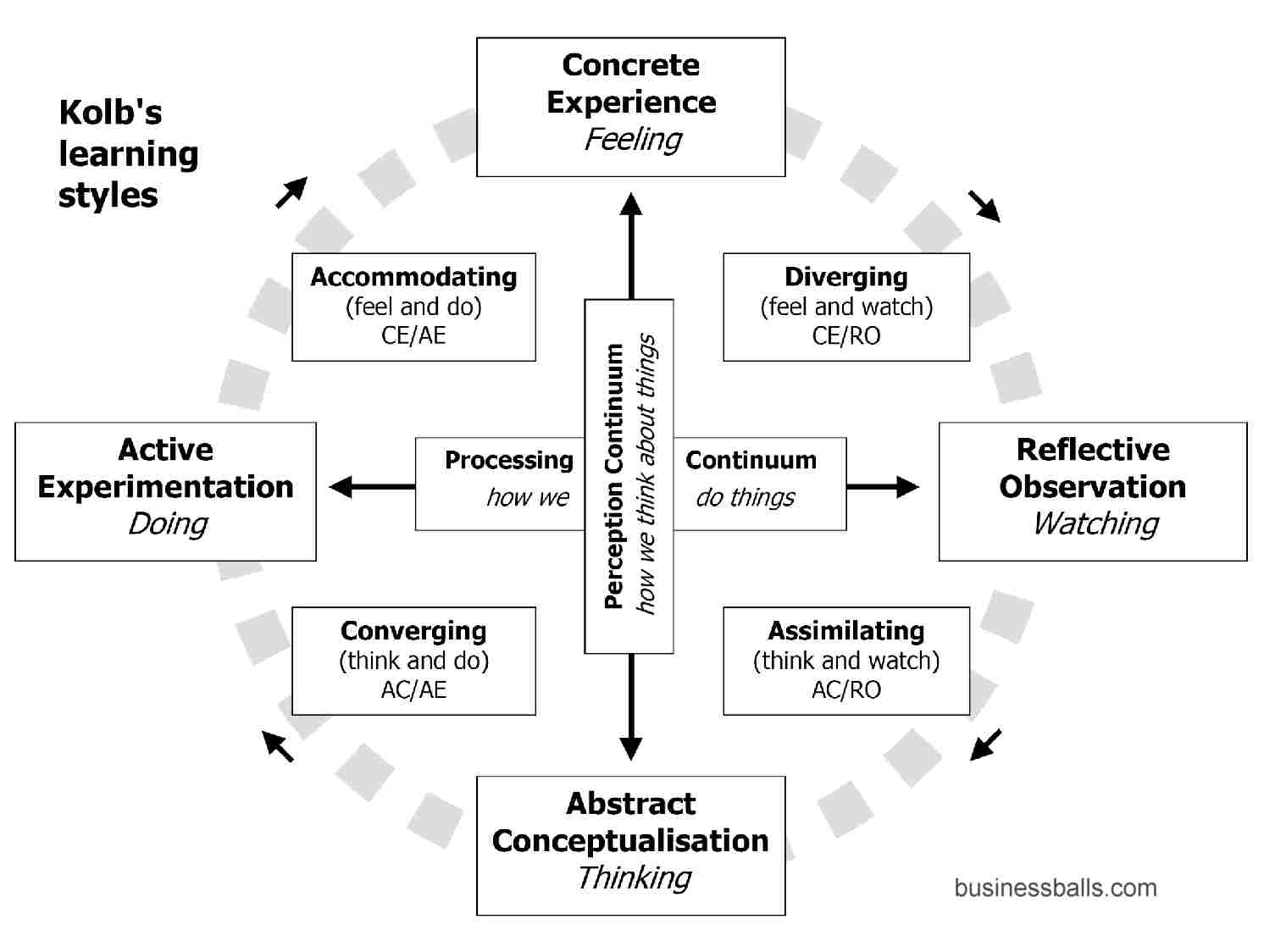

David Kolb - David Kolb (b.1939), an American educationalist, produced seminal works on experiential learning theory (see Kolb Learning Styles). In his 1984 book, 'Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development', Kolb extended the ideas of Kurt Lewin, Jean Piaget and others, about adult learning, to produce an experiential learning concept - often represented by Kolb's Learning Process Diagram. This famous diagram shows four main stages of the learning process, as a continuous loop, in order of:

- Experience,

- Reflection,

- Learning/Conclusion,

- Planning/experimentation (and then back to Experience...)

David Kolb's Learning Styles concept has become a classical model representing the way we experience learning in our everyday life and work, and how we learn best in a practical sense, moving between active and reflective modes, and specifically through the stages shown in the diagram:

(See Kolb Learning Styles for detailed pdf versions and explanations of this diagram.)

Kolb proposed that if we become better at using all the stages of the learning cycle, notably including reflecting on experience, we will become better life-long learners. In other words, if we learn better and have better outcomes, we will be more successful in life.

Kolb's concept is among many that advocates 'trial and error' (extending to reflection, conceptualization and experimentation) through our own direct personal experience, and asserts this ('trial and error' approach) as an important mechanism for successful learning.

Note: While this assertion stands alone as a learning model for many self-contained tasks and activities, of course we need more than personal experience to learn about the wider world. Reflective Practice is not the only learning process we need in life.

Wolfgang Köhler - Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967), a German gestalt psychologist born in Estonia, conducted learning studies using animals, in which he created the term 'insight learning'. He described his work in the 1917 book 'The Mentality of Apes'. Köhler expanded the notion of simple 'trial and error' to suggest a mental process which visualises a problem and considers a solution before taking action, triggering 'aha' or 'light-bulb' moments. For example, Köhler tells of observing an ape trying to retrieve a banana out of reach: the ape stops for a moment and then uses a nearby stick to pull the banana within reach. Köhler saw this as the 'insight' thought process leading to alternative action, i.e., visualising a problem and considering a solution before taking action. He presented this 'insight' as reflective thought, which equates to the 'reflective observation' stage in Kolb's learning cycle.

Donald Schon - Donald Schon (1930-1997) was an American philosopher, author, and Professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He produced a series of books on learning, Reflective Practice, and significantly, the development of reflective practitioners. His seminal work 'The Reflective Practitioner' (1983) focused on professional Reflective Practice and the role of the reflective practitioner. In his model, learning to reflect in action (RIA) and look back on action (ROA) together form a reflective process for decision-making and professional growth. Experiencing surprise or uncertainty during reflection in action could be described as 'light bulb' moments, as in Köhler's earlier insight studies.

Barbara Larrivee - Professor Barbara Larrivee is an American expert in teaching and Reflective Practice at the Department of Learning, University of California. She has written particularly about the use of Reflective Practice in classroom teaching, notably 'Transforming Teaching Practice: Becoming the critically reflective teacher' (2000) and her book 'Authentic classroom management: Creating a learning community and building reflective practice' (2005). Professor Larrivee agrees that insightful experience can trigger changes in outlook, necessary for critical Reflective Practice.

Reflecting on action gives us time to look back at what happened in a more measured and objective way. This builds on Dewey's (1933) concept of a purposeful reasoned process, delaying impulsive action to allow reflective judgement for action (US-English judgment).

Gillie Bolton - Gillie Bolton, a senior research fellow at King's College, London University, and later a writer and consultant, wrote the paper 'Reflections Through the Looking‐glass: the story of a Course of Writing as a Reflexive Practitioner' (1999) and 'Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development' (2010). Bolton says in her 1999 paper: "... Professionals are under increased pressure: roles have become more complex, demand has increased, staffing levels have decreased and constant accountability is essential. Stress levels are unsurprisingly higher. The examination of practice [work/life experience] can improve understanding, knowledge, skills and therefore delivery. Writing as a reflective practitioner can lead to professional development, decrease stress by enabling problems to be discussed and dealt with, and can also support the building of team work..." Bolton focused on reflective writing techniques, which she called 'through the mirror' writing. She defines separately and connects Reflective Practice and reflexivity as 'cognitive states of mind', and uses narrative accounts to examine actions of self and others.

Carl Rogers - Carl Rogers (1902-87) was a prominent American psychotherapist and author. His books include 'Client centered Therapy' (1951), and 'Becoming a Person' (1961). Carl Rogers asserted that self-awareness is crucial for personal growth. He regarded critical reflection as vital for promoting learning and self-assessment, enabling us to identify and evaluate our skills and development needs. This in turn leads to more proactive personal and professional development planning and continuing professional development (CPD). Self reflection helps us to develop problem solving skills and find solutions in planning action for behaviour change. In reflecting on experiences, we can understand how we learn, start to observe our own progress in learning, limits of understanding, and develop more effective critical thinking skills by questioning and analysing our own and others' behaviour. In this way, we can begin to understand ourselves and be more self critical in a positive way. Rogers was a particular expert on empathy (understanding other people's feelings) and a great advocate of the importance of empathy in objective thinking, which is explained later in Reflective Practice objectivity.

Michel Foucault - Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French philosopher and social theorist. Significantly his view was mainly of society, and saw personal reflection as an aspect of societal health. In his work 'The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality' (Vol 2, 1992 pp8-9, published posthumously), which built on his original 1976 'History of Sexuality' book, he discussed the value of using reflection to consider how to go beyond the limits of our existing knowledge, in order to work towards intellectual growth and freedom. He defined critical self-reflection as being: "To know how and to what extent it might be possible to think differently, rather than legitimating what is already known … a test of the limits that we may go beyond..."

N.B. Foucault's perspective is an example of the evolution of Reflective Practice, in terms of its potential reach and outcomes, i.e., at a societal level, way beyond the earliest notions of reflection as simple aimless contemplation. Foucault's ideas prompt us to see very easily that Reflective Practice is ultimately a tool by which society and civilization can improve, far beyond notions of individual self-improvement and professional development. We could imagine for example that Reflective Practice, were it taught in schools, would before long help to increase participation in democratic processes, community engagement, population health/lifestyle improvement, etc. Here Reflective Practice is potentially a highly complementary concept alongside Nudge Theory, and The Psychological Contract.

Karen Kitchener - Dr Karen Strohm Kitchener (born c.1950), is an American Counselling Psychologist and author, and Professor Emeritus at the University of Denver, having directed its counselling program for almost 25 years. Dr Kitchener is internationally renowned for her work on adolescent development and reflective judgment, and ethics in psychology. In her article 'Cognition, metacognition and Epistemic Cognition in Human Development' she describes and defines the reflexive process of metacognition, as being: "...To monitor our own learning, to become aware of the limits of our knowledge, and to become aware of our own values, assumptions, and expectations, and how they affect our behaviour and relationships..." Dr Kitchener is among several modern experts whose work extends the potential for Reflective Practice into societal consequences.

Jack Mezirow - Jack Mezirow (1923-14) was an American sociologist and Emeritus Professor of Adult and Continuing Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. He is generally considered founder of the transformative learning concept, which divides knowledge into three types: Instrumental, Communicative, and Emancipatory. Mezirow asserts that examining our outlook on the world, and challenging the assumptions and preconceptions underlying our values and beliefs, can be emotionally threatening. Challenging the values and beliefs that form part of our self identity can challenge the very core of who we are. Conversely Mezirow's work suggests that self-reflection can empower us to be more open and emotionally capable of change and reflection: a liberating process of intellectual and emotional growth. In his 2000 collaborative book 'Learning as Transformation - Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress', Mezirow defines transformative learning as incorporating the examination of assumptions, to share ideas for insight, and to take action on individual and collective reflection. Mezirow offered the following transformative learning structure:

- Critical reflection on one's assumptions

- Discourse (communication) to validate insights from the critical reflection

- Action

Daniel Goleman - Daniel Goleman (b. 1946) is an American psychologist, author and science journalist. He wrote the best-selling 1996 book 'Emotional Intelligence' and is jointly acknowledged as originating and defining the EQ concept. Emotional Intelligence is popularly abbreviated to EQ. EQ significantly alludes to and contrasts with IQ (Intelligence Quotient), because EQ theory tends to regard IQ as a highly limiting way to measure human intelligence, and especially to judge broader human capability. Among more recent influences, Goleman referenced and developed some very old ideas in developing EQ principles, notably those of Greek philosopher Socrates, dating from 400BC. The Socratic 'know thyself' became a modern theory of self-awareness and emotional growth through the development of intrapersonal and interpersonal skills and social relationships. Goleman defined four social competencies for emotional growth, requiring self-reflection:

- Self-awareness

- Social awareness

- Self-management

- Relationship Management

Significantly in Goleman's work, the use of self-reflection should be regulated by the situation, which acknowledges the potential of reflective techniques to open deep personal issues, which may not be appropriate. For example, in the context of work-based management training, EQ-driven self-awareness should be explored safely within agreed professional boundaries, so as to avoid being too personal or introspective. Emotional Intelligence is a good example of a highly complementary theory to use alongside Reflective Practice.

Stephen Brookfield - Dr Stephen Brookfield (b.1949) is an English educationalist, at the School of Education, University of St Thomas, Minneapolis. In his book on 'Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher' (1995) he takes a wider view of critical reflection. Within his 'lens' theory, he suggests we reflect on our practice [work/life experiences] through other lenses, not only from our own perspective but from multiple perspectives; and including reflecting on theory. For example; seeing another person's point of view (colleagues, manager, customer) and reflecting through the lens of theory (books, internet, TV, training and development). This can enable us to find a more objective and less subjective picture of ourselves. Dr Brookfield described 'critical reflection' in 1995 as:

"The [Brookfield] 'Lens theory' suggests that apart from reflecting on our own personal beliefs, we reflect through other lenses, on multiple perspectives including theory..." (1995:p30)

This is a sophisticated and multi-faceted perspective Reflective Practice, and illustrates the evolution of the concept from its simple 'reflection' origins.

Critical reflection is viewed by many as the cognitive process linking theory and practical work, vital in critical thinking. Theory, and especially research and evidence-based facts - help us to understand the world beyond our own experience. Reflecting on theory - combined with personal experience - offers a potent basis for inspiring new ideas to put into effect, to achieve continuous improvement and development.

Systematically using reflection to consider what theory has to offer for our own learning and professional work can help us move from thought to action. After all, theory based on solid research evidence is largely recycled 'best practice' from the relevant field of study. Organizational theory is mainly drawn from studies in the workplace, and specifically for example, the management theorist Meredith Belbin's research into management teams has created a body of knowledge and understanding about team dynamics and effectiveness. The business world has used this wider knowledge to understand how to minimize errors in recruitment and team working, and to improve team effectiveness for improved productivity and growth. Dewey supported the idea of theory drawn from practical experience and applied back to practical action - a loop of reflection and action, for learning and development.

Reflexivity and reflective learning together empower critically reflective learners for continuous improvement in performance, at individual and organizational levels. These powerful implications for learning suggest that the reflective practitioner can transcend basic training and knowledge transfer, to instead facilitate real growth in people and in groups, and the fulfilment of human potential (US-English fulfillment).

Objectivity

Objectivity is a crucial aspect of Reflective Practice. This has been suggested from the start of its modern appreciation, among others, notably in the work of Immanuel Kant and Bertrand Russell.

The nature of thought is obviously personal, being the product of our own brain, so our own thinking tends to be subjective to some degree. Where our thinking is very subjective, for example when we feel very emotional about something, this subjectivity can become unhelpful, especially if we are stressed or angry, or upset, which can substantially distort interpretations.

If reflective thinking is to be useful for our learning and development, and for improving our actions and decisions in an environment, then this reflective thinking must include some objectivity. If decisions are based on wrong data, then outcomes tend to be unhelpful, or worse.

So objectivity is important if Reflective Practice is to be very useful.

We should consider what experts have said about this, and how we might best allow for natural human tendencies towards subjective thinking within Reflective Practice.

Jurgen Habermas - German sociologist and philosopher Jurgen Habermas (b. 1929) held a professorship at the University of Frankfurt until retirement in 1994. He suggested that reflection does not sit easily within a modern Western culture based on scientific reasoning (1998). From this perspective, reflective activities may be seen as too subjective and not sufficiently rooted in evidence, which is considered to be a more valid effective way to find truth.

The problem exists mainly because of two potentially different view of what is 'true':

- Truth seen as universal (objective and rooted in evidence)

versus

- Truth seen as relative to place, time and context (subjective and rooted in social relationships).

This has led to reflection being seen as either:

- A systematic process of enquiry and problem solving, or

- A subjective self reflection based on perceptions (therefore flawed).

However, Schon and others have noted that even 'objective' evidence-based problem-solving methods can be flawed, if a habitual routine approach fails to question and challenge the status quo.

For example, a reasonable evidence-based reflection made in the 1970s would have concluded that a lack of computer skills was unlikely ever to be a serious obstacle to professional development (other than for computer scientists and programmers), whereas by 2000 it had become virtually impossible to maintain a normal domestic existence, let alone develop a career, without a good command of IT and online technology. This is an extreme example of how reliance on 'evidence' or 'facts' can produce an unreliable reflection, and also highlights how subjective reflections based on feelings can change according to mood, circumstances, time, etc.

Nudge theory, and the heuristics within it (especially the human tendency to place undue emphasis on 'evidence') are very useful in understanding why people can be misguided by apparent 'facts', and how this can have a huge effect on groups and society.

Some types of subjective instinctive thinking is unhelpful, but other types can be tremendously effective in finding truth and solutions.

So we need to be more subtle in understanding what objectivity and subjectivity mean in relation to Reflective Practice.

We can increase our objectivity by increasing our awareness of our assumptions and expectations. Or put another way, we will reliably increase our objectivity in Reflective Practice by recognising our assumptions and expectations, and being able to differentiate this data from objective facts and evidence.

Each of us has a different individual outlook on the world. This develops from the circumstances and influences that shape us into adulthood. Our reflections are filtered through these beliefs, values and attitudes, so that our interpretations are likely to be biased. Our thinking is instinctively 'value-driven'.

To achieve a more objective view, we can reflect on our prejudices and assumptions.

This approach is very much aligned with notions of metacognition, (awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes).

We can also use objective evidence to support our reflections, and in this way reduce bias in interpreting events and experiences.

Truth requires objective confirmed evidence. Subjective reflections can be faulty, especially when based on perceptions alone.

So particularly when reflecting on human values and social relationships we can increase the validity of our reflections by using evidence.

Nevertheless subjective reflections can be valuable, provided we are aware of the dangers of bias.

Moreover, while isolated reflections are often unreliable and transient, a collection of subjective reflections can produce a meaningful picture. This 'whole picture' tends to be greater than the sum of its parts.

Searching for new knowledge or truth towards our own personal development requires more than merely increasing objectivity, and reducing the potential for bias inherent in subjective interpretation; we must draw on both of these data sources, weighing and balancing them to formulate thinking which is informed by:

- Facts and evidence, and other objective data, and

- Personal relative reactions and feelings, and other subjective data, and

- Our analysis of what these things mean, their relative validities and their most reliable blend.

Lawrence-Wilkes and Ashmore - Linda Lawrence-Wilkes and Dr Lyn Ashmore, teachers of professional development in higher education in northern England, collaborated to publish their research on Reflective Practice for learning, 'The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education' (2014).

Lawrence-Wilkes and Ashmore propose that:

As we reflect on new ideas and knowledge, we can stand back to gain new insights as patterns emerge to create a more holistic picture.

Like seeing stars in the night sky - it can be difficult to see them at first - we see just a black sky - but when our eyes become sensitive to the stars, we see more and more of them. Our initial struggle to see a single star naturally resolves, as we absorb more detail, so that we can eventually discern increasingly complex patterns, and eventually vast constellations. Yet when we first begin looking we cannot see a single star.

So, like star-gazing, in adopting a critical attitude - we must allow the whole picture to develop. We must be open to an evolving picture - to adopt a questioning stance, and to look beyond the surface to find truth.

Kitchener and King (1990) suggest a reflective judgement model promoting 'reasoned reflection':

- Judgements are based on what is most reasonable, using contextualized evaluation to determine the validity of data.

Here 'contextualized' means that we consider data - subjective and objective - according to its context, so that facts and feelings are not seen in unreliable isolation.

Building on these ideas, Lawrence-Wilkes and Ashmore propose an integrated model of critical reflection which acknowledges a social context.

This requires a reflective approach that accepts and respects diverse perspectives, supported by evidence, and produces shared and inclusive knowledge.

The Johari Window model offers a very helpful view of this principle.

The combination of:

- Self-reflection (self)

- And collective reflective communications (self plus others)

produce a wider reflective approach, which then contributes to shared knowledge at micro and macro levels (i.e., detailed/personal/local, and broad/external/societal).

For example:

Shared reflections in the classroom, through disseminated written/published works, contribute to wider bodies of knowledge.

And at a personal level, someone who reflects on may progress to take action for change in wider society.

And at a personal level, someone who reflects on their personal and professional life may build on strengths and address development gaps to progress and take action for change in wider society.

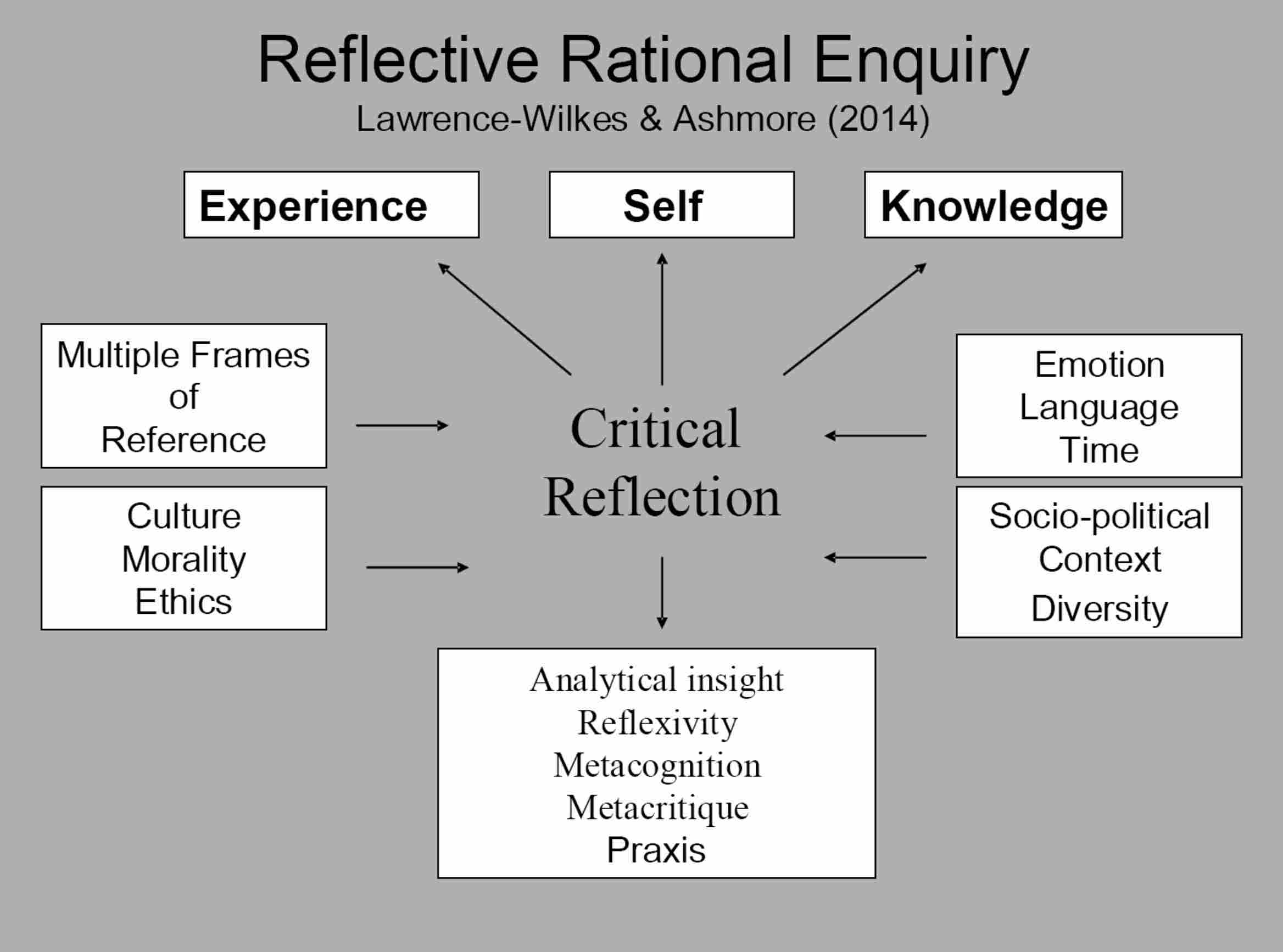

The Reflective Rational Enquiry diagram below supports critical reasoned reflection through an integrated reflective-rational approach.

(Diagram source ref: Lawrence-Wilkes and Ashmore, 2014:64, The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education.)

In the diagram's context, here are definitions of terms not already explained or self-explanatory:

- Multiple Frames of Reference - different world views or outlooks.

- Metacritique - wide and deep critical evaluation or analysis of something, including previous critical review ('meta' here means higher-ordered, or a superior level)

- Praxis - commitment to action (as opposed to theory or thought about something - praxis is ancient Greek meaning 'doing' - more generally now it means 'practice' in the sense of practical action)

The Lawrence-Wilkes/Ashmore model argues for:

- More reliable personal reflection about our inner-self, and

- Critical reflection and enquiry as to outer experience and knowledge in the wider world.

Knowledge and experience are interpreted and analysed through the filter of perception and context, using reflective activities to obtain new insights for independent thinking and action.

Process and Methodology

When we put Reflective Practice into effect we are actually seeking to make a change, by using subjective and objective data from experience, to plan and decide actions.

In more detail, this process is (to the fullest extent of the concept, in reverse):

- A plan or experiment or action that we devise,

- Which is based on our learning,

- Which is from relevant experience and information,

- Which might be positive and/or negative, and a mixture of:

- Objective facts, evidence, knowledge, etc., and

- Subjective feelings, instincts and personal reactions,

- All of which, ideally, we have assessed to understand its meaning for us, and its validity and relevance for the particular situation.

This section seeks to convey some methods for using Reflective Practice - either for yourself, or to help others use the concept.

It's helpful to revisit what reflection within Reflective Practice actually means, since reflection crucially assists us to make successful change.

Jenny Moon - Jenny Moon is a Teaching Fellow and Associate Professor at Bournemouth University. She has written much on reflective learning and the use of learning journals to support professional development. In her book 'Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice' (the word 'practice' there refers to practical work), she defines reflection as a thought process: "[Reflection is] ...a mental process of thinking about what we have done, learned and experienced..." (J Moon, 1999)

Most of us reflect superficially all the time, about what we are doing during events or experiences in our daily lives. Some call this 'thinking on our feet' (a metaphor based on thinking while acting, which contrasts with more deliberate concentrated thought).

This expression 'thinking on our feet' often refers to a lack of preparation or reacting to a suprising situation, although its deeper meaning is that we are reflecting about a situation 'in the moment', in a broad external sense, and also an internal personal sense.

While reflecting 'in the moment' is valuable, and can produce effective immediate solutions, we might not develop these reflections beyond the event itself, and not retain these valuable pieces of reflective learning when we move on to other tasks.

If however we think more proactively, more deliberate reflection can generate conclusions and actions for making future improvements, preventing repeated mistakes, and other positive change.

'Thinking on our feet' (immediate reactive reflection) can solve immediate challenges, whereas critical reflection (i.e., after-the-event proactive reflection) can produce more complex changes for future improvements.

Put very simply, thinking about a task as we are doing it can lead to making changes to improve the outcome of the task.

For example, if I put a bundle of white clothes in the washing machine and see that the water has turned a blue, I am thinking I might have left a blue sock in the bundle, or a blue pen that was in my shirt pocket.

Noticing and reacting to what happened does not guarantee I won't make the same mistake again, whereas reflecting more deliberately about what happened can help me to think about what I can do to:

- Repair the damage and

- Avoid it happening again (I will definitely check what I am putting into the machine next time!)

In the above example, note the stages of Kolb's learning cycle:

- I had an experience,

- I reflected on it, to evaluate what went well or badly

- I considered some ideas and options for change

- And planned a different action.

If I remember next time to check the clothes properly before I put them into the machine I should achieve a better outcome, i.e., a clean white wash. And then extending my reflective thinking, besides checking pockets properly, I may reflect on other methods to get an even whiter wash.

This simple but often-overlooked principle is reinforced by the old saying that:

"If we keep on doing the same things, we are likely to get the same outcomes..."

also often shown as:

"If you always do what you've always done, then you'll always get what you've always got..."

It is important to remember that having reflected about and understood a problem experience, that we evaluate our strengths/weaknesses and examine how these might affect the situation. We can then make the changes that our learning has enabled us to plan.

We can probably all recall times in our lives when we have failed to reflect on a negative experience, consequently failed to consider options for change - and so a repeat of the mistake becomes inevitable.

It is a nuisance if all our white clothes eventually become blue, but if we fail to reflect and take corrective action in more serious areas, results can be catastrophic - for example in a busy hospital, or manufacturing aircraft components.

Reflection can help us:

- Understand our own strengths and weaknesses, and become better learners,

- Encourage and plan development of our capabilities,

and potentially more crucially -

- Adopt and apply Reflective Practice in the workplace, in professional situations, so that..

- Very serious risks are minimized,

- Quality on a wide scale is optimized,

- Others adopt and use similar Reflective Practice methods,

- And ongoing improvement and risk avoidance become deeply embedded into organizational culture, to avoid stagnation and encourage innovation.

Using Reflective Practice

We can start using Reflective Practice by simply (and mindfully, intentionally) thinking about things that have happened in our lives, whether in a personal or professional situation.

We can reflect in lots of different ways on a range of different events or experiences that are important to us.

Using Reflective Practice does not require any extra time..

For example, on our journey home from work or study, (especially on public transport when we don't need to concentrate on traffic) we can devote a little time to consider things that happened during the day.

We can reflect while walking the dog, doing the washing-up or ironing, cutting the lawn, cleaning, and even when watching TV - you'll be surprised at how much time is spent sitting in front of a TV not actually engaged with what's on screen, just day-dreaming, in a trance. Instead, we can use and build on these moments to trigger deliberate reflection.

We might think about one particular event or situation, or a series of events or experiences: what went well, what might not have gone quite so well, and what we could have done better or different to make our day more successful.

When To Reflect About An Event

We usually reflect to a degree about an event when it happens or very quickly afterwards, however by reviewing it later usually we can see it differently, and discover different feelings about it.

The timing of Reflective Practice - especially in relation to stressful/intense experiences - can be crucial.

Transactional Analysis, and its underpinning theory - offer very relevant details as to why and how our emotions can become heightened, so that our mood and attitudes distort from a more normal evenly balanced viewpoint. This helps us consider how emotions can affect social relationships.

Lawrence-Wilkes offers an example from her teaching experience of the deliberate scheduling of Reflective Practice so that it does not immediately follow an intense mood-altering event:

Reflective Practice can be very useful for people learning/experiencing and reviewing very intense training activities such as self-defence (US-English defense), control and restraint techniques, etc.

It's long been recognized that the quality of reviews in such situations can vary greatly, depending on how quickly the review follows the event.

For this reason, reviews held very soon after intense training/incidents are called 'hot'. Reviews that are conducted some hours afterwards are called 'cold'.

During 'hot' reviews, Reflective Practice among trainees is typically greatly influenced by their emotions and reactions to the event's pressures (as in the expression 'in the heat of the moment'). This emotional sensation, usually very subjective, naturally happens due to the production of stress and action hormones in our nervous systems. The event may also 'trigger' unconscious feelings that were embedded by trauma/stress in the past. Mindful of these possible effects, it's very important to conduct a 'cold' review sufficiently later than the event when emotions have cooled (which may be in addition to, or instead of, the 'hot' review immediately after the event). This 'cold' review process enables Reflective Practice that is clearer, more balanced, and objective. This in turn improves the quality of reflections; the examination of our own role and responsibilities in the situation; and the resulting judgments and decisions about future actions.

Note that 'hot' reviews can themselves be very valuable - provided people understand that they are 'hot', and that people focus on how emotions can affect the way we behave.

Moreover, if you are teaching people about Reflective Practice, then it can be very helpful to demonstrate the difference between 'hot' and 'cold' reviews, rather than merely avoiding 'hot' reviews altogether. This can be especially useful in group situations, and relates strongly to the Johari Window principle and model of self/mutual-awareness.

Emotions can feature strongly in people's reflections - especially in organisations which suffer from 'blame culture' - i.e., where people are quick to blame others or external reasons for poor outcomes, rather than take personal responsibility and concentrate on finding solutions. This type of 'attribution' of blame is very unhelpful for Reflective Practice.

Accordingly take extra care in facilitating group reflections wherever emotions are likely to distort people's views of their own behaviour and its consequences.

In any situation, remember that emotions can significantly influence our perceptions about an experience, and timing (or reflection in relation to an event) can significantly influence our emotions.

So where appropriate, delaying our reflection usually enables us to see things more clearly, minimising distortions caused by emotions.

The excellent Fisher theory of personal transition is also a very useful aid to understanding how time alters our feelings about events, especially our reactions to a pressure for change.

Techniques and Media for Reflective Practice

While written records are helpful and memorable, especially for personal individual reflection, reflections do not always have to be in writing.

This is particularly so where a group (or more than one person) is involved in Reflective Practice, so that reflections can be shared through discussion. The discussion can then lead to collective agreement about future actions, changes and improvements. See the Johari Window for help relating to group relationships.

Individually or in groups, reflective Practice can be managed via various 'media', for example:

- Written journal, notes or diary (see the reflective diary templates/tools)

- Creative imagery - e.g., 'mind-mapping', sketches, pictures, diagrams

- Reflective dialogue and discussion - in groups, couples, etc., face-to-face or by phone or written, etc., and with a mentor or coach

- Social media - blog/twitter/online communities

- Academic study - qualitative research, research process, reflective texts

- Published work - article, book, conference

When deciding what methods/media to use, consider the basic process for effective Reflective Practice requires a deliberate way to link, and progress through stages of:

- Reflection

- Understanding

- Action

During this process be mindful of the requirements to:

- Reflect at the right time - Reflect at appropriate times in relation to any experiences which are stressful or intense (intense experiences need a cooling-off period before 'cold' reflection is possible).

- Balance subjective and objective reflection - Be aware of the difference between your subjective reflection and your objective reflection - both are useful and relevant, but you must understand what is subjective and what is objective, and you must strive to balance each in arriving at the most helpful and clear overall understanding.

- Understand how and why you think in the way you do - generally and about specific things - this is 'metacognition' - ("Awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes.")

- Consider your personal role and responsibilities - examine your strengths, skills and development needs (for example assess your multiple intelligences to understand your different skills and abilities - and perhaps find new ones)

- Seek external clarifications - Refer to external references, advice, information, clarifications, facts, figures, etc., especially where you believe that your thinking is not factual enough, or you are not fully informed about situations. (See heuristics tendencies within Nudge Theory, which offer helpful alerts to our natural human vulnerability to making assumptions, blind faith, unsupported fears, following the crowd, etc).

The place where you reflect can also be significant. The Emergent Knowledge concept, in which a person's location can have a dramatic effect on thinking, and aid the stimulation of different attitudes or unlock feelings. This might be simply standing rather than sitting, or moving to a different part of the room, or relocating greater distances. Try it.. move to a different room or outdoors, and experience how your mood and perceptions alter.

Activities such as walking, swimming, yoga, and exercising can also produce dramatic shifts in thought patterns. For example, taking exercise is proven to reduce stress levels, especially in countryside or green spaces, and this is certainly beneficial for reflection.

So reflection techniques are not restricted to the process of reflection itself - they extend to managing the situations, locations, and the mind/body condition in which you reflect.

Comparing Models

Various experts have produced Reflective Practice models to help people use Reflective Practice more deliberately, proactively, and effectively.

These models also help beginners to remember the process of reflecting from events/experiences for effective learning, and can also restrict (unhelpful) 'creative narrative reflections', in which we develop subjective thinking into fanciful or fearful imaginings. See the Murphy's Plough story, for example.

Rolfe et al (2001)

First, this very simple and memorable model offers a very flexible process for using Reflective Practice, and especially for getting started and experimenting with the concept.

- What? - What happened?

- So what? - What does it mean?

- Now what? - What needs to happen next?

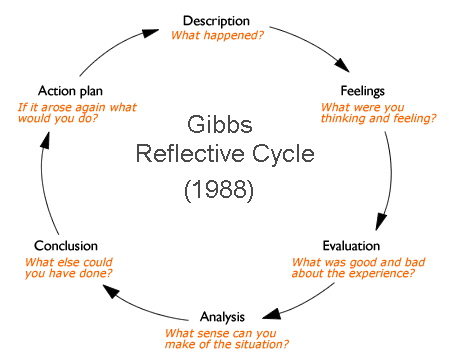

Gibbs - Reflective Cycle model (1988)

The Gibbs' reflective cycle, inspired partly by Kolb's learning cycle, enables us to focus especially on our own and others' feelings, views and perceptions. In common terms people call this "Standing/walking in someone else's shoes". This relates strongly to ideas about empathy.

The process is essentially a cycle or loop, containing the following elements:

- Description - What happened?

- Feelings - What were you thinking and feeling?

- Evaluation - What was good and bad about the experience?

- Analysis - What sense can you make of the situation?

- Conclusion - What else could you have done?

- Action Plan - If it arose again what would you do? (back to 1 Description)

(Diagram: Gibbs G [1988] Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford. [Brookes.ac.uk])

Having empathy can help us to see beyond our own actions, feelings and motivations to imagine how another person might be feeling; what their different views and opinions might be; and how these factors can influence the situation.

It is usually easier (and therefore a natural tendency) to blame others for problems, than to consider our own responsibilities in a particular situation.

Also, we can only change what is in our control to change.

The Gibbs model encourages the use of critical reflection, and especially offers a good starting point for people first using Reflective Practice, in converting new learning and knowledge into action and change.

The process requires that we look beneath the surface of events and experiences, to achieve deeper levels of reflection and learning.

REFLECT

This is a very neat 'bacronym' (an acronym devised in reverse to fit a word) based on the word 'REFLECT', representing stages of Reflective Practice:

- Remember - Look back, review, ensure intense experiences are reviewed 'cold'. (Subjective and objective)

- Experience - What happened? What was important? (Subjective and objective)

- Focus - Who, what, where, etc. Roles, responsibilities, etc. (Mostly objective)

- Learn - Question: why, reasons, perspectives, feelings? Refer to external checks. (Subjective and objective)

- Evaluate - Causes, outcomes, strengths, weaknesses, feelings - use metacognition. (Subjective and objective)

- Consider - Assess options, need/possibilities for change? Development needs? 'What if?' scenarios? Refer to external checks (Mostly objective)

- Trial - Integrate new ideas, experiment, take action, make change. (Repeat cycle)

Here the model is shown in a table form, showing that it can be used as a template or tool for notes and actions, or other points.

|

Lawrence-Wilkes 'REFLECT' model of Reflective Practice |

|||

|

R |

1. Remember |

Look back, review, ensure intense experiences are reviewed 'cold'. (Subjective and objective) |

|

|

E |

2. Experience |

What happened? What was important? (Subjective and objective) |

|

|

F |

3. Focus |

Who, what, where, etc. Roles, responsibilities, etc. (Mostly objective) |

|

|

L |

4. Learn |

Question: why, reasons, perspectives, feelings? Refer to external checks. (Subjective and objective) |

|

|

E |

5. Evaluate |

Causes, outcomes, strengths, weaknesses, feelings - use metacognition. (Subjective and objective) |

|

|

C |

6. Consider |

Assess options, need/possibilities for change? Development needs? 'What if?' scenarios? Refer to external checks. (Mostly objective) |

|

|

T |

7. Trial |

Integrate new ideas, experiment, take action, make change. (Repeat cycle: Recall...) |

|

Self-Assessment Questionnaire

(You may use the tools in this website in self-development, research, and teaching/helping others provided you attribute their authorship and source and that you do not publish them or replicate them online.)

This quick Reflective Practice assessment tool indicates how and to what degree you use Reflective Practice.

The items are also a checklist of the main elements within Reflective Practice, enabling it to be effective and sustaining.

Score each item 0 = None; 1 = Some; 2 = A lot

| Reflective Practice Self-Assessment | |

| 1. To what extent do you reflect? | 0=No; 1=Some; 2=A lot |

| I make decisions about events as they happen. | |

| I change my behaviour or actions as events happen. | |

| I think about events and reasons for actions after they happen. | |

| I talk to others about events and behaviour after they happen. | |

| I think proactively after events to plan future action. | |

| I research/investigate issues to solve problems. | |

| Total of section 1. | |

| 2. What reflection methods/tools do you use? | 0=No; 1=Some; 2=A lot |

| I write notes which I review (e.g., diary, journal) | |

| I talk with others | |

| I explore theories, models, etc., that relate to my issues. | |

| I seek and get feedback from others about specific events / issues. | |

| I make image or audio records / interpretations of events / challenges. | |

| I observe events and situations that involve me carefully. | |

| Total of section 2. | |

| 3. Do you examine other points of view? | 0=No; 1=Some; 2=A lot |

| I understand my 'self' views - subjective and objective. | |

| I empathise with colleagues' / others' viewpoints. | |

| I seek standpoints of external theories and concepts. | |

| I look for relevant discussions (e.g., journal, article, conference). | |

| I look at research / evidence. | |

| I try to make objective sense of social media. | |

| Total of section 3. | |

| 4. What assumptions do you question? | 0=No; 1=Some; 2=A lot |

| My own ideas and beliefs. | |

| Other people's points of view. | |

| About task-related problems. | |

| About the way that I think, how and why (metacognition). | |

| I question books, newspapers, TV, etc. | |

| I question internet information. | |

| Total of section 4. | |

| 5. Your ability/freedom to reflect? | 0=No; 1=Some; 2=A lot |

| I have or make time to reflect. | |

| I have necessary reflection knowledge, methods, and tools. | |

| I overcome any self-imposed barriers, habits. | |

| I understand how/why I think as I do (metacognition). | |

| I am sufficiently empowered personally/at work. | |

| I am free of negative influence by others. | |

| Total of section 5. | |

| Total of all five sections. | |

| © Lawrence-Wilkes/Chapman, Businessballs 2015. |

|

Interpreting your scores:

There are a maximum 60 points available (5 sections, each of 6 questions = 30 questions, max 2pts each).

The total score indicates as follows:

0-20 - low interest/opportunity for Reflective Practice

21-40 - good potential for using Reflective Practice

41-60 - excellent potential for Reflective Practice (or you are already a critical reflector)

The individual element and sub-section scores indicate where you should direct your efforts to improve your Reflective Practice potential and capabilities.

Here is a more detailed Reflective Practice Self-Assessment instrument (pdf format) which includes sub-section analysis.

This process itself is a very good example of Reflective Practice, and using a Reflective Practice tool, and if you complete the questionnaire, analyse the results, and decide to take some action, then you are most certainly putting Reflective Practice to very powerful effect.

You may use the tools above in self-development, research, and teaching/helping others provided you attribute its authorship and source (© Lawrence-Wilkes/Chapman, Businessballs 2015, from Businessballs.com/reflective-practice.htm), and that you do not publish it or replicate it online.

Here are two other relevant free reflection tools:

Reflective Diary/Journal Process Guide and Templates (pdf)Reflective Diary/Journal Facilitative Questioning Process and Templates (pdf)

Linda Lawrence-Wilkes - biography

I am grateful to Linda Lawrence-Wilkes, an expert in Reflective Practice, for collaborating and contributing the technical content to this guide.

Linda's brief biography is a fine example of the adoption and purposeful application of Reflective Practice.

Linda Lawrence-Wilkes was born in 1949, in the industrial north of England. Raised in a working class family with no tradition of post compulsory education, Linda understood the climb out of poverty to make a meaningful life. She pursued career and educational opportunities, and began to use Reflective Practice to think more independently and adopt a critical stance. She understood the effort required to let go of the familiar and enter the unknown territory of new ideas and concepts.

"When I overcome my (many) barriers to learning and take on board new knowledge, I recognise new connections leading to new insights. A liberating process that empowers me to make the changes needed to be more successful in life and relationships. Today, I would see myself as a follower of critical theory and devotee of building critical skills to underpin emancipated thinking for intellectual liberation."

Linda works in higher education in the north of England (at 2016). Her work involves research and scholarship in higher education, and teacher training in the third sector. With the support of her mentor and co-author, Dr Lyn Ashmore, Linda published her research into how Reflective Practice can be used as a learning tool. The book is titled 'The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education' (see the reference list below).

The ideas expressed in the book have inspired Linda to collaborative in producing this guide.

Linda's contribution and collaboration in producing this guide to Reflective Practice is greatly appreciated. She is contactable via Linkedin or directly via email: llawrencewilkes at gmail dot com (NB that's LLAWRENCEWILKES - sorry it's not a link, so as to reduce spam).

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bolton, G. (2010) Reflective Practice, Writing and Professional Development (3rd edition), SAGE publications, California.

Brookfield, S. D. (1995) Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1910) How We Think. New York: Heath and Co.

Foucault, M. (1992) The Use of Pleasure. The History of Sexuality Volume 2, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, pp. 8-9.

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence. London: Bloomsbury.

Habermas, J. (1998) The inclusion of the Other. Studies in Political Theory. Parts VIII and IX of Ch1 Transcribed by Andy Blunden. London: MIT Press.

Kant, I. (1781/87) 2nd ed., Critique of Pure Reason, tr. and ed. by P. Guyer and A. Wood, (1998) Cambridge University Press.

Kitchener, K. (1983) 'Cognition, Metacognition and Epistemic Cognition' Human Development, 26, 222-223.

Kitchener, K.S. and King, P.M. (1990). The reflective judgment model: Transforming assumptions about knowing. In J. Mezirow et al (Eds), Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning (pp157-176). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Köhler, W. (1956) The mentality of apes. London: Routledge and K. Paul. (Original publication 1917 translated from 2nd revised ed by Ella Winter).

Kolb, D.A. (1984): Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development [internet] Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Larrivee, B. (2000) Transforming teaching practice: becoming the critically reflective teacher, Reflective Practice, 1(3), 293-307.

Lawrence-Wilkes, L., and Ashmore, L., (2014) The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mezirow, J. and Associates (2000) Learning as Transformation – Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Moon, J. (1999) Reflection in learning and professional development: theory and practice, London: Kogan Page.

Piaget, J. (1969) The Mechanisms of Perception, (G. M. Seagrim tr) London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, original work 1961.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. and Jasper, M. (2001). Critical Reflection in Nursing and the Helping Professions: a User's Guide. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Rogers, C. (1961) On Becoming a Person: A therapist's view of psychotherapy. London: Constable.

Russell, B. (1926) On Education, Especially in Early Childhood, London: George Allen and Unwin; repr. as Education and the Good Life, New York: Boni and Liveright, 1926; abridged as Education of Character, New York: Philosophical Library, 1961.

Schon, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books, New York. pp102-4 Lawrence-Wilkes, L., and Ashmore, L., (2014) The Reflective Practitioner in Professional Education, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan