The Psychological Contract

'The Psychological Contract' is an increasingly relevant aspect of workplace relationships and wider human behaviour.

Descriptions and definitions of the Psychological Contract first emerged in the 1960s, notably in the work of organizational and behavioural theorists Chris Argyris and Edgar Schein. Many other experts have contributed ideas to the subject since then, and continue to do so, either specifically focusing on the the Psychological Contract, or approaching it from a particular perspective, of which there are many. The Psychological Contract is a deep and varied concept and is open to a wide range of interpretations and theoretical studies.

Primarily, the Psychological Contract refers to the relationship between an employer and its employees, and specifically concerns mutual expectations of inputs and outcomes.

The Psychological Contract is usually seen from the standpoint or feelings of employees, although a full appreciation requires it to be understood from both sides.

Simply, in an employment context, the Psychological Contract is the fairness or balance (typically as perceived by the employee) between:

- how the employee is treated by the employer, and

- what the employee puts into the job.

The words 'employees' or 'staff' or 'workforce' are equally appropriate in the above description.

At a deeper level the concept becomes increasingly complex and significant in work and management - especially in change management and in large organizations.

Interestingly the theory and principles of the Psychological Contract can also be applied beyond the employment situation to human relationships and wider society.

Unlike many traditional theories of management and behaviour, the Psychological Contract and its surrounding ideas are still quite fluid; they are yet to be fully defined and understood and are far from widely recognised and used in organizations.

The concept of 'psychological contracting' is even less well understood in other parts of society where people and organisations connect, despite its significance and potential usefulness. Hopefully what follows will encourage you to advance the appreciation and application of its important principles, in whatever way makes sense to you. It is a hugely fertile and potentially beneficial area of study.

At the heart of the Psychological Contract is a philosophy - not a process or a tool or a formula. This reflects its deeply significant, changing and dynamic nature.

The way we define and manage the Psychological Contract, and how we understand and apply its underpinning principles in our relationships - inside and outside of work - essentially defines our humanity.

Respect, compassion, trust, empathy, fairness, objectivity - qualities like these characterize the Psychological Contract, just as they characterize a civilized outlook to life as a whole.

Please note that both UK-English and US-English spellings may appear for certain terms on this website, for example organization/organisation, behavior/behaviour, etc. When using these materials please adapt the spellings to suit your own situation.

Definitions and usage

In management, economics and HR (human resources) the term 'the Psychological Contract' commonly and somewhat loosely refers to the actual - but unwritten - expectations of an employee or workforce towards the employer. The Psychological Contract represents, in a basic sense, the obligations, rights, rewards, etc., that an employee believes he/she is 'owed' by his/her employer, in return for the employee's work and loyalty.

This notion applies to a group of employees or a workforce, just as it may be seen applying to a single employee.

This article refers to 'the organization' and 'leaders' and 'leadership', which broadly are the same thing in considering and describing the Psychological Contract. Leadership or 'the leader' is basically seen to represent the organization, and to reflect the aims and purposes of the owners of the organization. Leaders and leadership in this context refer to senior executive leaders or a chief executive, etc., not to team leaders or managers who (rightly) aspire to be leaders in the true sense of the word (covered under leadership, separately).

(Organizational aims and purpose at a fundamental constitutional level have potentially deep implications within the Psychological Contract which are addressed later, notably under additional perspectives.)

Where the term Psychological Contract is shown in books, articles, training materials, etc., it commonly appears as the Psychological Contract (capitalised first letters), but you might also see it in quote marks as the 'psychological contract', 'The Psychological Contract', or more modestly as the psychological contract, or sensible variations of these. Any is correct.

The common tendency to capitalise the first letters - Psychological Contract - as if it were a uniquely significant thing (a 'proper noun') like we do for names and important things like Planet Earth or the Big Bang or Wednesday. Personally I think the Psychological Contract is very significant and unique, but it's a matter of personal choice.

Accordingly on this webpage, where the term applies to the employment situation, it is shown as the Psychological Contract, or the Contract. This also seeks to differentiate it from a more general sense of 'psychological contracting' or 'contracts' or 'contracting' in wider human communications, mutual understanding and relationships.

The concept of the Psychological Contract within business, work and employment is extremely flexible and very difficult (if not practically impossible) to measure in usual ways, as we might for example benchmark salaries and pay against market rates, or responsibilities with qualifications, etc.

It is rare for the plural form 'Psychological Contracts' to be used in relation to a single organization, even when applied to several employees, because the notion is of an understanding held by an individual or a group or people, unlike the existence of physical documents, as in the pluralized 'employment contracts' of several employees.

The Psychological Contract is quite different to a physical contract or document - it represents the notion of 'relationship' or 'trust' or 'understanding' which can exist for one or a number of employees, instead of a tangible piece of paper or legal document which might be different from one employee to another.

The singular 'Psychological Contract' also embodies very well the sense of collective or systemic feelings which apply strongly in workforces. While each individual almost certainly holds his or her own view of what the Psychological Contract means at a personal level, in organizational terms the collective view and actions of a whole workgroup or workforce are usually far more significant, and in practice the main focus of leadership is towards a collective or group situation. This is particularly necessary in large organizations where scale effectively prevents consideration of the full complexities and implications of the Psychological Contract on a person-by-person basis.

That said, it is usual for the Psychological Contract to refer to one employee's relationship with an employer, or to an entire workforce's relationship with the employer.

The term 'contracting' (lower-case 'c') in the context of communications is not clearly defined yet, and does not normally refer to the Psychological Contract. As discussed later 'contracting' does specifically refer broadly to 'agreeing mutual expectations' within Transactional Analysis (a specialised therapeutic or coaching/counselling methodology), and conceivably within other forms of therapy too. (TA 'contracting' is specifically described within modern TA theory.)

The nature of the relationship in Transactional Analysis is somewhat different to that of employee and employer, although significantly the sense of agreeing on mutual transparent expectations within Transactional Analysis is very similar in spirit and relevant to the Psychological Contract in employment.

The term 'psychological contracting' is not typically used in referring to the Psychological Contract in the workplace, but may arise in the context of therapy. It would be helpful to us all for this expression and its related theory, as an extension of the Transactional Analysis usage, to become more generally used in human communications and understanding. In life, relationships and communications generally operate on a very superficial level. Opportunities to explore, understand, explain and agree mutual expectations are largely ignored or neglected - mostly through fear or ignorance. It is a wonder that humans manage to cooperate at all given how differently two people, or two parties, can interpret a meaning, and yet be seemingly incapable of seeking or offering better transparency or clarity.

The Psychological Contract is becoming a powerful concept in the work context. Potentially it is even more powerful when we consider and apply its principles more widely.

The psychological contract

A basic definition of the Psychological Contract appears in Michael Armstrong's excellent Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice (10th Ed., 2006): "...the employment relationship consists of a unique combination of beliefs held by an individual and his employer about what they expect of one another..."

Armstrong references Edgar Schein's 1965 definition of the Psychological Contract, as being (somewhat more vaguely) an implication that: "...there is an unwritten set of expectations operating at all times between every member of an organization and the various managers and others in that organization..."

Armstrong highlights other references, within which these points are especially notable:

"...Because psychological contracts represent how people interpret promises and commitments, both parties in the same employment relationship can have different views..." (DM Rousseau and KA Wade-Benzoni, 1994)

"...a dynamic and reciprocal deal... New expectations are added over time as perceptions about the employer's commitment evolve... concerned with the social and emotional aspects of the exchange..." (PR Sparrow, 1999)

Notice how those three definitions of the Psychological Contract cited by Armstrong progressively increase in their subtlety and sophistication.

Schein's view reflects the early identification of the concept in the 1960s. Later Rousseau/Wade-Benzoni acknowledge the significance of different perceptions of employee and employer. Later still Sparrow recognises the dynamic quality, and the social and emotional factors. This is not to say the respective writers did not all in some way appreciate the depth of the concept; but it is a helpful illustration of the tendency for the conceptual thinking about the Psychological Contract to evolve, which in part reflects the increasing complexity of the essential employer/employee relationship.

The definition of the Psychological Contract on Wikipedia (April 2010) is: "A psychological contract represents the mutual beliefs, perceptions, and informal obligations between an employer and an employee. It sets the dynamics for the relationship and defines the detailed practicality of the work to be done. It is distinguishable from the formal written contract of employment which, for the most part, only identifies mutual duties and responsibilities in a generalized form."

The UK Chartered Institute of Personal Development, which takes a keen interest in the concept of the Psychological Contract, defines the concept as follows (as at April 2010, in a paper revised in January 2009): "...It [the Psychological Contract] has been defined as '…the perceptions of the two parties, employee and employer, of what their mutual obligations are towards each other'. These obligations will often be informal and imprecise: they may be inferred from actions or from what has happened in the past, as well as from statements made by the employer, for example during the recruitment process or in performance appraisals. Some obligations may be seen as 'promises' and others as 'expectations'. The important thing is that they are believed by the employee to be part of the relationship with the employer..." The quoted extract in the above larger excerpt is referenced: 'Guest, D E and Conway, N. (2002) Pressure at work and the psychological contract. London: CIPD'. Professor David Guest of Kings College London is a leading figure in modern thinking about the Psychological Contract. You will see his ideas and models commonly referenced if you research the subject in depth.

Within these referenced definitions you will see already that the concept is open to different interpretations, and has a number of complex dimensions, notably:

- There are a series of mutual obligations on both sides (which include, crucially, intangible factors that can be impossible to measure conventionally).

- It is a relationship between an employer on one side and on the other side an employee and/or employees (which by implication distorts the notion of a formal contract between two fixed specified parties).

- The obligations are partly or wholly subject to the perceptions of the two sides (which adds further complexities, because perceptions are very changeable, and as you will see, by their subjective 'feeling' and attitudinal nature perceptions create repeating cause/effect loops or vicious/virtuous circles, which are scientifically impossible to resolve).

- Overall the Contract itself has a very changeable nature (being such a fluid thing itself, and being subject to so many potential influences, including social and emotional factors, which are not necessarily work-driven).

- And an obvious point often overlooked, within any organization the Psychological Contract is almost never written or formalised, which makes it inherently difficult to manage, and especially difficult for employees and managers and executives and shareholders to relate to (the Psychological Contract is almost always a purely imaginary framework or understanding, which organizational leadership rarely prioritises as more real or manageable issues - or leadership regards the whole idea as some sort of fluffy HR nonsense, and anyway, "Let's not forget who's the boss... etc etc" - so that the whole thing remains unspoken, unwritten, and shrouded in mystery and uncertainty).

Work used to be a relatively simple matter of hours or piece-rate in return for wages. It is a lot more complicated now, and so inevitably are the nature and implications of the Psychological Contract.

At this point a couple of diagrams might be helpful..

Diagrams

Much of the theory surrounding Psychological Contracts is intangible and difficult to represent in absolute measurable terms. Diagrams can be helpful in understanding and explaining intangible concepts. Here are a couple of diagram interpretations, offered here as useful models in understanding Psychological Contracts.

Venn diagram

Here is a Venn diagram representing quite a complex view of the Psychological Contract, significantly including external influences, which are often overlooked in attempting to appreciate and apply Psychological Contracts theory. Venn diagrams (devised c.1880 by British logician and philosopher John Venn, 1834-1923) are useful in representing all sorts of situations where two or more related areas interact or interrelate. The Venn diagram below provides a simple interpretation of the factors and influences operating in Psychological Contracts.

In the Psychological Contract Venn diagram:

vc = visible contract - the usual written employment contractual obligations on both sides to work safely and appropriately in return for a rate of pay or salary, usually holidays also, plus other employee rights of notice and duty of care.

pc = psychological contract - which is hidden, unspoken, unwritten, and takes account of the relationship references (r) between employee and market (which includes other external factors), also the employer's relationship with the market (also r), and the visible contract (vc). Note that only the visible contract (vc) element is written and transparent. All the other sections are subject to perceptions until/unless clarified.

(For referencing purposes this diagram is an original interpretation of the Psychological Contracts concept and was published first on this website in May 2010.)

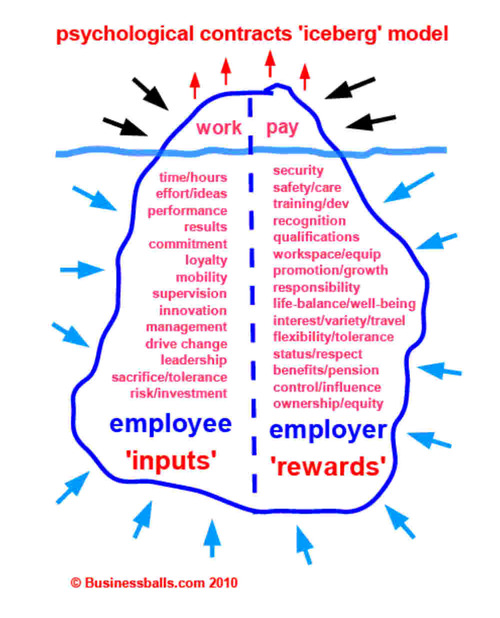

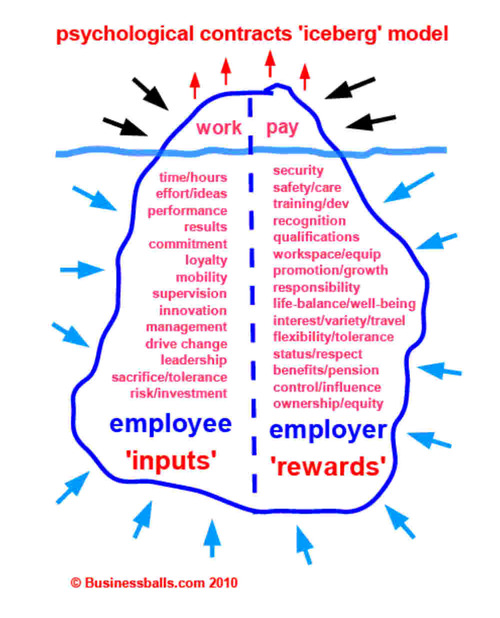

'Iceberg' model

This Psychological Contracts 'iceberg' diagram below is a helpful way to illustrate some of the crucial aspects and influences within Psychological Contracts theory.

For team-builders and trainers, and leaders too, it's also potentially a useful tool for explaining and exploring the concept and its personal meaning for people.

An iceberg is said to be 90% hidden beneath the water. This metaphor fits the Psychological Contract very well, in which most of the Contract perceptions are unwritten and hidden, consistent with its definition.

This is especially so for junior workers in old-fashioned 'X-Theory' autocratic organizations, where mutual expectations typically have little visibility and clarity. Here we might imagine that the iceberg is maybe 95% or 99% submerged.

By contrast the Psychological Contract between a more modern enlightened employer and its employees, especially senior mature experienced and successful staff, is likely to be much more clearly understood and visible, with deeper inputs and rewards, formally and mutually agreed. Here the iceberg might be only 60% or 70% submerged.

These percentage figures are not scientific - they merely explain the way the model works.

The iceberg metaphor extends conveniently so that the 'sky' and the 'sea' represent external and market pressures acting on employee and employer, affecting the balance, and the rise or fall of the iceberg.

As the iceberg rises with the success and experience of the employee, so does the contract value and written contractual expectations on both sides. Increasingly deeper inputs and rewards emerge from being hidden or confused perceptions below from the water-line, to become visible mutual contractual agreement above the water-line.

The process can also operate in reverse, although in a healthy situation the natural wish of both sides is for the iceberg to rise.

A quick key is shown with the diagram. A more detailed explanation is below the diagram.

Here is a PDF version of the Psychological Contract iceberg diagram.

Note that this diagram is an example of a very basic employee/employer relationship in which only work and pay are formally agreed and contracted. In reality a representation of the Psychological Contract for most modern work relationships would include several more mutual obligations with work and pay 'above the water-line', i.e., formally contracted and agreed.

Left side of iceberg = employee inputs (and employer needs).

Right side of iceberg = rewards given by employer (and employee needs).

Above the water level: factors mostly visible and agreed by both sides.

Work | Pay = visible written employment contract.

Black arrows = mostly visible and clear market influences on the work and pay.

Red arrows = iceberg rises with success and maturity, experience, etc., (bringing invisible perceived factors into the visible agreed contract).

Below the water level: factors mostly perceived differently by both sides, or hidden, and not agreed.

Left side of iceberg = examples of employee inputs, which equate to employer expectations - informal, perceived and unwritten.

Right side of iceberg = rewards examples and employee's expectations.

Blue arrows = influences on employee and employer affecting perceptions, mostly invisible or misunderstood by the other side.

(For referencing purposes this diagram is an original interpretation of the Psychological Contracts concept and was published first on this website in May 2010. Here is a PDF version of the Psychological Contract iceberg diagram.)

Explanation

The left side of the iceberg represents the employee's inputs. These are also the employer's needs or expectations, which may be visible and contractually agreed, or informal, perceived, inferred, etc., and unwritten, or potential expectations depending on performance and opportunity, which not not necessarily apply to all employees/employers.

The right side represents typical examples of rewards given by the employer. These are also the employee expectations or needs, which again may be visible and contractually agreed, or perceived, inferred, imagined, etc., in which case they would generally be unwritten. As with the left-side employee inputs, the right side of the iceberg also includes potential inputs which are not necessarily applicable to all employees/employers.

In both cases 'below the water-line' factors are strongly a matter of perception until/unless brought out into the open and clarified. Perceptions from the employee's standpoint are crucial, which tend to differ markedly from the employer's perceptions, and also from the employer's methods of assessing such factors. For example the employee may vastly over-estimate the value of his/her contribution to organizational performance. The employer may vastly under-estimate the stress or erosion of life balance that the job causes to the employee.

The examples of factors on the iceberg are not exhaustive, and the sequences are not intended to be matched or directly reciprocating. Many other factors can apply. I have referred already to the importance of encouraging open communications, without which a leader will never discover what the iceberg looks like, let alone how to manage it.

Above the water level - 'work and pay' - represents the basic employment contract - the traditional 'fair day's work for a fair day's pay'. This loosely equates to the 'vc' segment in the Venn diagram. This visible employment contract is typically the written contractual obligations on both sides. The iceberg diagram shows the the most basic work and pay exchange. In reality most workers are formally responsible for other inputs and are formally entitled to benefits beyond pay alone, so in this respect the iceberg here represents a very basic situation.

The black arrows represent market influences on work and pay, especially including those that are specific to the employment situation, which are obvious, visible, and known, etc. These influences would include specifics such as market demand for and availability of people who can do the job concerned. This extends to market rates of pay and salary.

The red arrows represent the tendency for the iceberg to rise with success and maturity in the job, and to a degree also in the success and maturity of the employer organization. More mature experienced and high-achieving employees will tend to see their personal icebergs rising so that increasingly the hidden contractual factors become visible, and written into formal employment contracts, above the water-line, so to speak. Employees generally want the iceberg to rise. So do enlightened and progressive employers. They want the hidden unwritten aspects of the Psychological Contract which are below the surface to become applicable, and to be visible and formalised contractually. A rising iceberg signifies increasing employee contribution towards organizational performance, which is typically rewarded with increasingly deeper rewards and benefits.

Below the water-line - the metaphorical 90% of the iceberg which is under the surface. These are the hidden perceptions which strongly affect interpretation of the Psychological Contract, notably by the employee. These factors loosely equate to the 'pc' area of the Venn diagram. Where the Psychological Contract is very largely hidden perceptions and mutually unclear, then we can imagine the iceberg being more than 90% submerged. Where the Contract is healthier and clearer - for whatever reason - we can imagine the iceberg perhaps being only 60-70% submerged. Interestingly, in cooperatives and employee ownership organizations the iceberg model will tend to be (due to the nature of the employee ownership model) mostly out of the water, and perhaps even floating on top, as if by magic, which is a fascinating thought..

The sequential listing of factors shown below the water-line on both sides is not definitive or directly reciprocating (of equal values). The model provides a guide to the concept, not a scientific checklist of equally matched or balancing factors. That said, the diagram offers a broad indication of relative seriousness of the factors in both lists, with the deeper items representing the most serious potential inputs and rewards, which tend to be matched by deeper elements on the other side.

Use the framework to map your own situation, rather than attempting to fit your own situation into the specific examples given.

The blue arrows represent hidden factors influencing employee and employer and notably affecting their perceptions and attitudes to each other. These factors may be very visible to and clearly understood by one side but not to the other until/unless revealed and clarified in objective terms. Many hidden influences are not well understood by either side. Many of these factors change unpredictably, but many are relatively constant and can easily be clarified. Both sides may assume the other side already knows about these factors, or alternatively has not right to know about these factors. Some factors are hidden because they are difficult for anyone to understand or predict, but a great many others result simply from secrecy, borne of distrust or insecurity.

Some employers and leaders will wonder how on earth all these hidden and subjective factors can possibly be identified and balanced. In fact they can't in absolute terms; but they can be made far more transparent and agreed if management philosophy and methods strive for good open positive cooperation between employer and employees.

Here is a PDF version of the Psychological Contract iceberg diagram.

A healthy Psychological Contract is one where both sides agree that a fair balance of give and take exists. This is impossible to achieve where there are lots of hidden perceptions, so the first aim is to encourage greater openness and mutual awareness. Given greater awareness most people tend to take a more positive approach to compromise and working agreements.

Various reference models help with this process, particularly the Johari Window, which is an excellent way to explore and expand mutual awareness.

Employers, leaders, team-builders, etc., wanting to explore the Psychological Contract with staff could invite people to sketch what they think their own icebergs look like. And then compare the results with how the leadership sees the iceberg, and also how the leadership imagines its people see the Psychological Contract. It would be interesting and helpful within such an exercise to attempt to label some of the external factors and pressures (the black and blue arrows) - especially the blue ones below the water line on both sides.

Context and implications

In management and organizational theory many employee attitudes such as trust, faith, commitment, enthusiasm, and satisfaction depend heavily on a fair and balanced Psychological Contract.

Where the Contract is regarded by employees to be broken or unfair, these vital yet largely intangible ingredients of good organizational performance can evaporate very quickly.

Where the Psychological Contract is regarded by employees to be right and fair, these positive attitudes can thrive.

The traditionally dominant and advantageous position of an employer compared to its workforce (or indeed of any other authority in relation to its followers, 'customers', or members, etc) means that the quality of the Psychological Contract is determined by the organizational leadership rather than its followers. An individual worker, or perhaps a rebellious work-group could conceivably 'break' or abuse the Psychological Contract, but workers and followers under normal circumstances are almost always dependent on the organization's leadership for the quality of the Contract itself.

This last point is intriguing, because in organizations such as employee ownership corporations and cooperatives, a different constitutional business model applies, in which workers and potentially customers own the organization and can therefore to a major extent - via suitable representational and management mechanisms - determine the nature and quality of the Psychological Contract, and a lot more besides. We see a glimpse here possibly as to how organizations (and other relationships involving leadership authority or governance) might be run more fairly and sustainably in future times. We live in hope.

Intriguingly also, several factors within the Psychological Contract - for example employee satisfaction, tolerance, flexibility and well-being - are both causes and effects. Feelings and attitudes of employees are at the same time expectations (or outcomes or rewards), and also potential investments (or inputs or sacrifices).

This reflects the fact that employee's feelings and attitudes act on two levels:

- Employee feelings and attitudes are strongly influenced by their treatment at work (an aspect of the Psychological Contract), while at the same time,

- Employee feelings and attitudes strongly influence how they see themselves and their relationship with the employer, and their behaviour towards the employer (also an aspect of the Psychological Contract).

The simple message to employers from this - and a simple rule for managing this part of the Psychological Contract - is therefore to focus on helping employees to feel good and be happy, because this itself produces a healthier view of the Contract and other positive consequences. Less sensible employers who ignore the relevance of employee happiness - or the relevance of the Contract itself - invariably find that the Psychological Contract is viewed more negatively, and staff are generally less inclined to support and cooperate with the leadership.

Aside from this, a major reason for the increasing significance of, and challenges posed by, the Psychological Contract is the rapid acceleration of change in business and organised work. This modern dramatic acceleration of change in organisations, and its deepening severity, began quite recently; probably in the 1980s. Some leaders do not yet understand this sort of change well, or how to manage it.

Autocratic leaders, which we might define as 'X-Theory' in style, are probably less likely to appreciate the significance of the Psychological Contract and the benefits of strengthening it. Modern enlightened people-oriented leaders, which we might regard as Y-Theory in style, are more likely to understand the concept and to develop a positive approach to it. (See McGregor's XY-Theory - it provides a helpful perspective.)

An old-style autocratic X-Theory leader might say: "I pay the wages, so I decide the contract..."

Here the Psychological Contract is unlikely to be particularly healthy, and could be an organizational threat or weakness.

An enlightened Y-Theory leader is more likely to take the view: "People work for many and various reasons; the more we understand and meet these needs, the better and more loyally our people will perform..."

Here the Psychological Contract is more likely to be fair and balanced, and is probably an organizational strength and even a competitive advantage.

The most enlightened and progressive leaders will inevitably now find themselves considering the deeper issues of employee ownership and representational leadership.

Increasing complexity

The nature, extent and complexity of the Psychological Contract are determined by the nature, extent and complexity of people's needs at work.

Work needs are increasingly impacted by factors outside of work as well as those we naturally imagine arising inside work.

People's lives today are richer, more varied, and far better informed and connected then ever. People are aware of more, they have more, and want more from life - and this outlook naturally expands their view of how work can help them achieve greater fulfilment.

Work itself has become far more richly diverse and complicated too. The working world is very different to a generation ago.

The employer/employee relationship - reflected in the Psychological Contract - has progressively grown in complexity, especially since workers have become more mobile and enabled by modern technology, and markets globalized. These changes began seriously in the 1980s. Prior to this many modern dimensions of work - such as mobile working, globalization, speed of change - were unusual, when now they are common.

Below the grid gives examples of how work has changed. The watershed might have been the 1980s, or maybe the 90s, it depends on your interpretation; but the point is that sometime around the last two decades of the 20th century the world of work changed more than it had changed since the Industrial Revolution, which incidentally was from about the late-1700s to mid-1800s.

Globalization and technology in the late 20th century shifted everything we knew about organized work onto an entirely different level - especially in terms of complexity, rate of change, connectivity and the mobility of people and activities.

There are also significant changes under way specifically involving attitudes to traditional corporations, markets and governance. Examples of extremely potent 'community' driven enterprises are emerging. Social connectivity and technological empowerment pose a real threat to old-style corporate models. Younger generations have seen the free market model and traditional capitalism fail, and fail young people particularly. Certain industries no longer need a massive hierarchical corporation to connect supply and demand.

The significance and complexity of Psychological Contract have grown in response to all of these effects, and given that the world of work will continue change in very big ways, so the significance and complexity of the Contract will grow even more.

How work has changed since the 1980s

| up to 1980s | after 1980s |

| work teams | virtual teams |

| factory/office working | home/mobile-working |

| line management | matrix management |

| customer service | call centres |

| in-house services | outsourcing and off-shoring |

| job for life | job for 2 years |

| a life's work | a career for 10 years |

| onsite services | online services |

| few employee rights | many employee rights |

| low employee awareness | high employee awareness |

| employees isolated | employees connected |

| reliable pensions | unreliable pensions |

| other issues: equality, discrimination, training, qualifications, sharesave, pensions, buy-to-let, 4x4s, telephone, letters, mainframe computers and terminals, sub-contracting, employment contracts | other issues: life-balance, sabbaticals, lifelong-learning, employee ownership, community, social enterprise, email, social networking, mobile web, globalization, the psychological contract |

It is easy to understand given this dramatically shifted backdrop that people's relationships with their employers have altered a great deal.

Just one of these factors would be sufficient alone to change substantially how employees relate to employers, and vice-versa - but all these features of work, and more besides, are now quite different to how they were a generation ago.

This new shape of organized work is a fundamental driver of the nature of the Psychological Contract, and also of its significance for employers, especially during economic growth and buoyancy, when employees have more choice and flexibility compared to the relative power of employers during periods of recession.

When considering the 'before-and-after' grid above in relation to the Psychological Contract the initial reaction can be to focus on the erosion of traditional outputs (benefits, rewards, etc) accruing to employees, such as job and career security, pensions, etc. Extending these issues, the tendency is to imagine that the changing nature of the Psychological Contract presents more of a challenge or threat to employees than employers.

This is not necessarily so. The shifting world of work (and life beyond work) presents some threats to employers, and erosions of the employee inputs traditionally taken for granted by employers. The changes in work and life that continue to re-shape the Psychological Contract have a two-way effect; they present risks and opportunities (and advantages and disadvantages) to employers and employees alike.

Notably, workers are increasingly mobile, flexible and adaptable - they no longer stay dutifully working for the same employer for as long as the employer needs them. Good workers can far more easily find alternative employment than twenty years ago. They are not limited to working in their local town, or region, or not even in the same country. In fact with modern technology geographical location is for many workers irrelevant, and will become more so.

Also consider the connectivity of workers today. In past times, trade unions were the vehicle for people-power. Instead, increasingly today the vehicle is the internet and modern social networking, which enable awareness and mobilisation of groups of people on an awesome level of sophistication and scale, the effects of which we are only beginning to witness.

Modern technology, which the younger generations understand and exploit infinitely better than older people, is fantastically liberating for employees. Historically workers relied on employers for access to technology. In the future, employers will progressively depend on employees for its optimisation.

Training and development was a big aspect of employer control. Employees depended on their employer to advance their learning and skills, and thereby their value in the employment market. This is no longer the case. Employees are progressively able to control their own learning and development, again through modern technology, and a new attitude of self-sufficiency is emerging, which we have never seen before.

Leaders were historically focused on retaining customers. Increasingly they will have to focus just as much on retaining staff. A new generation of workers has grown up with no expectation of a job for life. They seek variety and change, where their parents sought routine and security. Moreover they have access to, and control over, substantial modern technologies which will continue to evolve in favour of the individual, rather than the organization.

Leaders must therefore lead in a different way, if they are to retain the best people, and to develop better relationships and reputation among staff, customers and opinion-formers.

Interestingly there are still plenty of leaders (in business and wider governance) whose ideas of power and authority are a lot closer to the practices of the early industrialisation of work, than to the modern world. This may be so particularly in the UK, which is still dogged by old systems and attitudes of class and elitism. The signs are that much of this old thinking will be forced to change - and be reflected within the Psychological Contract - as people, at the level of employees, followers, citizens, customers, etc., become more empowered.

Leadership transparency

This is worthy of separate note and emphasis because it's a big factor in organizations of all sorts.

Lack of leadership transparency results from one or a number of reasons:

- assumption by leadership that employees already know

- assumption by leadership that employees aren't interested, or are incapable of understanding

- thoughtless leadership - not even considering transparency to be a possible issue

- belief by leadership that employees have no right to know

- a policy of secrecy - to hide facts for one reason or another

First let's put to one side those situations where a leadership intentionally withholds facts and operates secretively because it has something to hide. Achieving a healthy Psychological Contract will neither be an aim or a possibility for such employers.

More commonly in other situations, lack of transparency exists due to leadership negligence, fear or insecurity, or simply a lazy old-fashioned 'X-Theory' culture, all of which can be resolved with a bit of thought and effort, and which can produce dramatically positive results, because:

Leadership transparency has a huge influence on two major factors within the Psychological Contract and its effective management:

- employee trust and openness towards the employer

- employee awareness of facts - enabling employee objectivity in judging the Psychological Contract

Where leadership is not transparent, employees have no reason to trust the employer, and according to human nature, will tend not to be open and trusting in return. As discussed elsewhere in this article, trust is crucial for a healthy Psychological Contract.

And where leadership fails to inform and explain itself openly and fully to employees, employees will form their own ideas instead, which tend not to be very accurate or comprehensive. Wrong perceptions, especially when we add misinformation, rumour, etc., thrive in an information vacuum. Faulty beliefs become hidden factors (among the blue arrows in the iceberg diagram) which influence the Psychological Contract very unhelpfully. Aside from this, ignorance and uncertainty make people feel threatened and vulnerable.

Lack of leadership transparency is a particularly daft failing where clear explanation of organizational position provides real objective justification for a particular organizational action or inflexibility.

Transparency helps to kick-start a 'virtuous circle' within the Psychological Contract, as well as giving employees reliable facts about their situation.

The 'virtuous circle' enables trust, openness and tolerance to develop. Reliable facts replace faulty assumptions and unhelpful perceptions.

Lack of transparency starts a 'vicious circle'. Distrust fosters distrust. Secrecy fosters secrecy. Employer/employee communications will tend to be closed, not open. Fear and suspicion on both sides increase, particularly in employees, whose perception of the Contract worsens as a result, in turn increasing animosity and fear.

'Virtuous and vicious circles' within the Psychological Contract are explained in more detail later in this article.

Note that this advocation of transparency does not give leaders the right to unburden themselves constantly of the worries and pressures that typically come with the responsibility of leadership. Followers expect leaders to be transparent where people are helped by knowing, so that they can prepare and react constructively.

Transparency here refers to the easy and helpful availability of information about the organization. It's similar to openness, discussed later, which is more concerned with honest two-way communications within an organization. These are not fixed definitions of transparency and openness; just an attempt here to explain two different aspects of organizational and management clarity.

Transparency tends to be a matter of leadership policy, style, by which clear facts about an organization's position, activities and decisions are made available to its employees and ideally also to its customers. Openness tends to refer to the flow of communications in all directions within the organization, here especially the feelings, ideas and needs of employees. Good general levels of openness in communications may have no influence at all on improving leadership/organizational transparency, especially if the organization chooses not to be very transparent. Transparent organizations find it much easier to foster open communications.

Change management

Change management is a big challenge in today's organizations, and it is very significant in the Psychological Contract.

Organizational change puts many different pressures on the Psychological Contract.

So does change outside of organizations - in society, the economy, and in individuals' personal lives; for example 'Life-Stage' or 'generational' change - (see Erikson's Life-Stages Theory).

Our ability to understand and manage organizational change increasingly depends on our ability to understand and manage the most important drivers within the Psychological Contract.

Nudge theory offers very helpful ways to understand how and why people think and respond to change-management.

These can vary considerably situation to situation. We need therefore to be able to identify and interpret the nature of change, and other factors impacting on the Psychological Contract, rather than merely referring to a checklist. People's needs, and their perceptions of their needs, can change quickly, and tend to do so more when they are unhappy.

Organizational leaders naturally see change from their own standpoint. Crucially, to manage change more effectively leaders must now see change in terms of its effects on employees, and must understand how employees feel about it.

Managing change is often seen as merely a process - as in project management for example - but effective leadership style and behaviour - notably alongside a modern appreciation of the Psychological Contract - are also vital for successful change management.

Where a leader's behaviour is sensitive to people's feelings, change happens much easier. Where a leader forces change on people insensitively, and without proper consideration of the Psychological Contract, then problems usually arise.

These two approaches extend interestingly in different ways, which we can call a 'virtuous circle' or a 'vicious circle'.

'Selling' changes

The extent to which change, or any situation, is 'sold' to people warrants careful consideration.

'Selling' here refers informally to the use of persuasion, influence or incentive, in causing someone or a group to do something they would probably not otherwise do, which commonly in management and business seeks to achieve the acceptance of a proposition or other sort of change.

When change has to be 'sold' to people, it's normally because whoever is doing the selling suspects that people might not willingly accept the situation were it to more openly and objectively explained.

Persuasion can produce mutually positive outcomes in some situations - especially if the people being persuaded are comfortable and open to the approach - but persuasion which amounts to 'selling' change is often not helpful or constructive for those being persuaded, and may not actually produce a good outcome for the persuader either.

This particular effect is very significant within the Psychological Contract.

'Selling' change - especially unfairly or strongly - tends to produce a negative outcome for everyone.

This is a simple way to decide usually what is fair and what is unfair when 'selling' or persuading others to agree to or accept change:

- Motivating and encouraging people to apply a positive constructive approach to achieving or handling properly explained challenges is generally a good thing.

- Distorting the challenge or situation so that it is made to look acceptable or even advantageous is not.

Both of the above could be described as persuasion, but they are quite different approaches. Where there is a sense that change has to be 'sold' to people, it's a sign that that the approach is probably not fair and could produce problems later.

For those preferring a more tangible perspective than fairness, we could substitute the notion of risk, or risk avoidance:

Methods of communicating change which involve distortion of deceit carry greater risk of conflict and negative outcomes than methods which explain the situation clearly, while offering motivation, support and encouragement, etc.

People need to know what lies ahead, and to be consulted and supported in dealing with it.

Leaders have a duty to give proper information and explanation to their followers. Leaders neglect a fundamental responsibility where they deceive people or distort facts, in the hope that people will somehow absorb the problem when it looms larger than promised, or worse where a leader takes the view that people have no right to know or to complain.

I'm not advocating negative thinking in assessing and communicating change. I'm advocating objectivity and honesty. People don't like nasty surprises and they don't like dishonesty, especially when it stems from authority trying to reduce resistance to change or to avoid obligations arising.

This is an important aspect of change management and of relationships generally, and because it involves trust at a deep level, it is very relevant to the Psychological Contract.

Usually where change is 'sold' to people the Psychological Contract is damaged.

Employers tend to minimise or 'spin' the negative effects of change. Doing so (initially) makes the change easier and quicker to manage, and reduces the difficulties for the leader, so in this respect it's perhaps a natural human tendency, as well as a common organizational behaviour. The short term appeal of glossing over or otherwise distorting hard facts often encourages leaders to neglect deeper discussion and debate where it might be warranted.

'Selling' change is usually a short-term gain, with a long-term cost, plus interest.

Employees may be fooled initially when a leader 'sells' them a change without properly and honestly explaining its implications. They may even be enthused by the change. This all turns very bad indeed however when a change, 'sold' on a false premise, turns out to be worse than first presented. Employees feel bad because of the new unpleasant situation, but they feel even worse because they can now see they've been deceived, or fooled or conned.

Also, where change is 'sold' to people using strong persuasion or distortion or omission, they naturally struggle to cope as well as they might have done if they'd been given a fair chance to prepare.

Many changes are difficult and cannot be avoided of course. Always though, it is best to be open and honest with people. This gives people time to absorb and react. They feel good because they've been trusted and treated as adults, not children. They may even come up with helpful ideas and suggestions - they often do - which the leadership might not remotely have imagined possible. Most importantly by being open and honest with people - preferably involving them at the earliest possible stage - the essential relationship and trust within the Psychological Contract can be protected far more easily.

Nudge theory - a powerful change-management concept which emerged in the early 2000s - is potentially very useful in understanding and managing change, especially where resistance among people seems strong, and conventional approaches are failing, or causing conflict.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability or process used in understanding the other person's situation and feelings.

We normally characterize empathy as the behaviour of a single person, but in the Psychological Contract empathy must be an organizational capability - a cultural norm and expectation of leaders and managers in their dealings with people.

Empathy is crucial to trust, cooperation and openness, and it's also crucial to mutual understanding. All of these elements are significant within the Psychological Contract, so empathy is too.

The nature of empathy is that people can see if it exists or not. Where it does not, building trust and cooperation is very difficult.

Where an employer lacks empathy, employees naturally are less inclined to trust and cooperate. A 'vicious circle' begins.

The nature of many organizations, and a traditional view of management, commonly puts the employees at the bottom of the management hierarchy. It's partly human nature, perhaps reinforced by experiences of authority in childhood and schooling. It's also the way that authority has been for thousands of years.

Having raised the point I should add that it might not always be like this. The world is changing in some very interesting ways. We are beginning to see authority in various contexts shifting back to followers, and separately due to similar forces (notably technological and connective empowerment of people), certain types of authorities are beginning to see and describe themselves as servants rather than leaders.

That said, authority in most businesses and organizations will continue for some while to see itself at the top of the pile.

The underlying attitude of this sort of authority tends to impose its views and to project its interpretations onto the people who are subject to the authority.

This attitude is very unhelpful for modern work and management, and especially for the Psychological Contract.

Where leadership has this attitude, it cascades down through management. This is a big obstacle to improving the quality of the Psychological Contract, because it is an obstacle to empathy.

Empathy is lacking where authority fails to truly understand and recognise the feelings, needs, views, etc., of its followers/employees.

Achieving a fair balanced Psychological Contract requires that important factors are understood, and seen to be understood. The more an employer demonstrates broad awareness of the employee situation, the more likely it becomes that mutual agreement - and a healthy Psychological Contract - can be established and maintained.

Many employers, especially businesses, accepted a generation ago that empathy is vital when dealing with customers - to build trust, and to know what customers truly feel, think and need. Businesses realise that customers' needs change according to changes in the market and the wider world, and that these needs can be very complex and dynamic. They need to be understood by using empathy and building trust, and appropriate responses provided, or the relationship between supplier and customer is broken or lost altogether.

The analogy is significant.

Progressive employers are realising that exactly the same principles apply to the Psychological Contract with employees.

Virtuous circles and vicious circles

When an employee feels bad, he/she tends to look for someone to blame. We all behave like this at times, especially when our emotional reserves and self-image are low. When an employee looks for someone to blame he/she tends to put the employer high on the list. The perception of the employer worsens. The Psychological Contract stinks mostly because the employee feels bad.

Conversely, when an employee feels good and the self-image is strong, he/she tends to see the employer more positively. "I like my work (and my boss) because I feel good.." The Psychological Contract now smells of roses.

This is not new. This sort of loopy effect has always existed. It's unavoidable within any proper appreciation of the Psychological Contract. These loops are not conventionally measurable, but they do exist and can be very significant.

Within the Psychological Contract many perceptions become an important part of the reality. A traditional X-Theoryemployer/leader might dismiss employee perceptions as not being real or relevant. The traditional autocratic view is "...To run a corporation we must deal in reality and not worry about perceptions..." However if the workforce believes (perceives) that the leadership is being heavy-handed, or greedy, or neglectful, or unethical, then this is the reality which the leadership needs to address, because such perceptions have a huge effect on the Psychological Contract. Perceptions are part of the reality and dismissing them doesn't make them disappear.

We cannot manage every conceivable element in the Psychological Contract, especially when we try to imagine the detailed personal needs of large numbers of employees within a big organization.

Happily employees do not normally demand such attention to detail, provided they are satisfied that their major needs of trust and fairness are met.

Beyond a certain level of consultation and involvement, employees are generally accepting of decision-making by leaders. Employees have their own jobs to do and (ideally) enjoy doing them; many do not aspire to be leaders themselves, or to do the work of a leader, and so are happy to assume that leaders are making good decisions in good faith - particularly if, again, essential elements of trust and fairness are seen to exist.

What is it then within the Psychological Contract that sometimes causes relatively small factors to be big problems in some situations, but not in others?

An explanation can be seen in the 'virtuous circles' - or 'vicious circles' - that operate within the model.

Helpfully - for employers who have a positive approach to the Psychological Contract - people's needs at work tend to reduce and simplify when the Psychological Contract is healthy. We see a 'virtuous circle' operating.

When people are happy at work they are more emotionally positive, resilient and flexible. These attitudes make it easier for people to adapt to and accept change, and to tolerate and be flexible in response to unexpected demands or irritations.

This is true in life generally, not just in work. To handle change - or any potentially negative effect - we need strong emotional reserves.

When people are happy and emotionally strong at work they are more likely to assist in the change process. This is extremely useful in big organizations, where change is usually ever-present and ongoing.

This 'virtuous circle' makes managing organizational change much easier, and it means that employees are less likely to react in a big negative way to a relatively minor incident or anomaly within the overall Psychological Contract.

Emotionally positive people tend to be resilient and flexible. They also tend to rationalize (explain to themselves and others) events in a positive way, even events that in other circumstances might be regarded as potentially threatening.

Positive attitude, mood, and frame of mind are very powerful in turning perceptions and opinions into helpful realities.

It is human nature for happy satisfied people to see the bright side of things, just as it is human nature for unhappy dissatisfied people to see the negative and to fear the worst.

Negative emotion is a very powerful driver of employees' unhelpful needs and dependencies at work. Unhappy workers find plenty to be dissatisfied about; they demand more support and help; they need more managing; they feel worse about themselves, their work, their boss, their employer, their pay, and life as a whole. They also moan to colleagues, who will often moan back, and reinforce negative feelings. And so, unhappy employees are emotionally not able to be very tolerant or flexible when their employer needs them to be, which makes managing the Psychological Contract much more difficult. In terms of change management this can be disastrous to organizational performance, and in terms of the Psychological Contract, it stinks, because that's how the employees feel about it. This is a 'vicious circle'.

Try motivating people and providing brilliant service to your customers in that situation. It's not easy.

Sadly and typically the vicious circle accelerates if managers and leaders then retaliate or exhibit negative emotions towards employees. We see this commonly in publicised industrial disputes, and you might be imagining now as you are reading this the sort of leaders and organizations who perform so incompetently in such situations. Temper tantrums and bullying regrettably enable many poor leaders to advance way beyond their true level of ability (see the Peter Principle, which partly explains how). The behaviour is not very sustainable however.

Transactional Analysis methodology is very useful in understanding aggressive confrontational leadership, and potentially also in rehabilitating leaders so afflicted, if they can be persuaded to attend therapy..

Openness of communications

Openness of communications is crucial to within the Psychological Contract and to 'virtuous and vicious circles'.

Open communications in an organization become 'virtuous circles'. Closed communications become 'vicious circles'.

Leadership generally determines and controls the level of organizational transparency, whereas openness of communications, or lack of, depends on wider issues of culture, processes, management methods and attitudes, etc.

Organizational/leadership transparency is quite simple to achieve where the leadership has a will to do so. Achieving openness of communications is usually a much bigger and more complex challenge.

Significantly within the Psychological Contract openness is the preparedness of employees to be open and honest about their feelings to their employer, which usually depends on the employer (and its management) being open and honest with the employees.

Openness of communications produces lots of other organizational benefits, but in terms of the Psychological Contract openness crucially influences trust and mutual awareness (between organization and employees, i.e., both sides of the Contract), and through the 'virtual/vicious circle' effect openness hugely influences the quality of the Psychological Contract.

Secretive distrustful employees are extremely difficult to manage. The organization has no real idea of what they want, nor what their priorities and concerns are. The employer may not even realise that a problem exists until it blows up into a major crisis.

Open communications between employer and employees are a strong indicator of a healthy Psychological Contract, and also of a capability to accommodate change. Open communications enable change to be managed, and problems to be resolved. The characteristic is both cause and effect - a 'virtuous circle'. When openness is offered, encouraged and acted upon helpfully by the employer, employees themselves become more open, and also more accepting of change and other challenges.

Closed, secretive communication between employer and employees suggests the opposite - an unhealthy Psychological Contract - and this effect tends also to be self-fuelling - a 'vicious circle'. Murphy's Plough is a helpful and amusing analogy. This sort of behaviour is obviously very obstructive when trying to manage organizational change. Closed communications inevitably produce 'blind' arbitrary leadership decisions and changes from which people feel excluded. This creates fear and negativity among staff, which closes communications further and increases suspicion, resentment and resistance.

The 'virtuous circles' within the Psychological Contract offer a naturally efficient way to build tolerance, flexibility and adaptability and other positive characteristics among employees within the Psychological Contract.

The 'vicious circles' aspect reminds us that where a leader fails to foster positive attitudes and communications - or worse, displays distrust, aggression, animosity, etc - this causes employees generally to be less tolerant of anomalies, even small ones, within the Psychological Contract.

I repeat the point that leadership openness and transparency must not extend to leaders unburdening themselves of worries and pressures arising in the responsibility of leadership. Openness chiefly applies to the flow of honest constructive communications within an organization, especially enabling the building of mutual trust and awareness between leaders/managers and followers (for which the Johari Window is a very relevant and useful model).

External and relative reference factors

There are for each of us many and various shifting external and/or relative reference factors and which influence our judgement as to what is right or fair or reasonable in our lives.

Many external references become internalised or personalised, affecting our 'frame of reference' and how we value and compare situations and especially alternative options.

Nudge theory is very useful in understanding how these external references and comparisons affect people's thinking - and in discovering many other influences on people's thinking, which otherwise often remain hidden and unknown.

Psychological Contracts depend heavily on relative factors. People cannot think about the Psychological Contract with their employer without reference to external and relative factors.

Adams' Equity Theory provides a very helpful viewpoint of this.

For example how we perceive our market worth as an employee has a substantial influence on the value that we imagine our employer should place on us: A person who has secured an alternative job offer at a higher salary than his current employment will tend to expect more from his current employer than a person who has attended a dozen job interviews in the past year and received no job offer.

Here is a different example of how consideration of the psychological contract can greatly depend on external factors:

Imagine a banker's attitude to his employer six months before the 2008 global financial crash. Employment was buoyant, bonuses were high, performance and stocks were booming. A senior banking employee would tend to feel bullish and confident. He/she would tend to feel that his/her job is safe, and that other jobs elsewhere are available. The market generally favoured employees. Largely a good performer could pick and choose where to work. Now contrast that with a time six months after the 2008 global financial crash. Banking job vacancies were relatively scarce. Redundancies were rife. Bonuses were slashed (for a while). Those in work are not so bullish or confident. It was no longer an employees' market; it was an employer's market. The external market had changed, and with it the employee's perceptions, and reality, as to his/her relative value, and the relative value (and increasingly, security) offered by the employer. The employee in 2009 had a different interpretation of his/her Psychological Contract - specifically reduced expectations - than the same employee with the same employer before the 2008 crash. The employee is the same; the employer is the same; the financial and tangible package might be the same (it might even have worsened in terms of bonus and job security), and yet the employee in 2009 almost certainly would view the Psychological Contract as being more acceptable than it was in 2008. Of course perceptions can go down, as well as up..

The banker scenario is an obvious and extreme example, nevertheless external and relative factors are everywhere in everyone's view of work, and in life outside work, and these factors are often hidden until we think or ask about them, and many can be very significant in influencing people's feelings, perceptions and expectations.

Relative factors tend to be very difficult to measure.

Imagining a scientifically balanced formula for just a small set of 'give and take' (inputs and rewards) within the Psychological Contract is difficult enough. The notion of a mathematical model covering every possible exchanges, and allowing for external/relative factors, is even more mind-blowing.

We should instead aim to identify, understand and clarify the biggest external relative factors and then react to them fairly and realistically.

Pareto (80/20) analysis methods are useful in assessing the most important factors within a complex series of possibilities.

If we clarify the major confusions, fill the big information gaps, and satisfy people's major needs, then the remaining smaller incidental or occasional issues - which will be countless in a large workforce - will generally take care of themselves through the 'virtuous circle' rule.

Remember that the Psychological Contract is not measurable or manageable in conventional ways. It needs approaching partly through tangible facts and logic, and partly through intuition, trust, and a level of pragmatism too. (I use the word pragmatism here not in its negative sense of rigidity or officiousness, rather in the sense of "dealing with matters according to their practical significance..", as the OED puts it - which is what the Pareto Principle helps us to do.)

Generational factors

While not necessarily external, generational issues are very interesting relative factors, and often overlooked. This generational model offers a simple and entertaining angle. Erikson's Life-Stage Theory offers a different and deeper perspective.

Our frame of reference changes quite markedly as we get older and pass through different life stages.

I am not suggesting that a detailed generational analysis be conducted of every employee's unique situation in order to arrive at a properly balanced Psychological Contract. I am suggesting instead that generational issues can be influential factors within employee needs and feelings, and so they need some consideration. This is obvious in an ageing workforce, or a very young workforce, but it's also worth consideration where distinctly different generational groups work together.

A practical example is that older people (see Erikson again) are commonly interested in helping younger people - passing on their knowledge, mentoring, for instance. Younger people value this sort of help. Isn't it logical then to consider these generational capabilities and needs in the broad thinking about the Psychological Contract?

When considering age be mindful of the laws about ageism and age equality. Generational factors must not be a basis of discrimination, but they can and should be a basis of understanding people's deeper needs and capabilities.

Additional and deeper perspectives

You will see many and various definitions of the Psychological Contract. It is a complex concept when examined beyond its most basic principle, and is dynamic when considered in any single situation: it's not fixed or static - it contains forces and feelings which can fluctuate and be quite chaotic.

The basic principle - that people seek fair treatment at work - is simple. Complexities and dynamics however come to life as soon as the principle is seen in a practical context; essentially the Psychological Contract is driven by people's feelings - therefore it's an effect which cannot be measured or defined in fixed terms like a salary or a timesheet. We might more easily try to define love or fear, or life itself.

As a concept, the Psychological Contract will continue to evolve and change, in both its effects and its definitions.

This complexity and dynamism is not surprising. The Psychological Contract combines the effects of at least two highly complicated systems:

- an individual person's thoughts, and

- an organization's behaviour towards that person.

Beyond this other complex systems are almost always involved:

- the thoughts of fellow employees;

- the thoughts and attitudes of leaders

- the positions and needs of the organization's ownership;

- the organization's behaviour towards fellow employees;

- the organization's performance and strength (especially the employee perceptions of this);

- the market in which the employer operates (again employee perceptions of this);

- the wider economy and world in which the employee sees him/herself (again employee perceptions of these factors);

- and perhaps most fundamentally of all, the constitutional or corporate structure of the organization concerned (notably the extent of separation/alignment between employees and the organization itself - ownership, purpose, rules, policies, equity, profit, performance, growth, reward, direction, etc - the extent to which the employees are genuine 'stakeholders').

Basic descriptions of the Psychological Contract tend to simplify the concept as merely the addition of intangible input/reward factors (such as loyalty and effort/job security and satisfaction) to the traditional tangible pay/hours and other clear measurable mutual obligations found within a conventional contract of employment.

In modern times more advanced and sophisticated views of the Psychological Contract are emerging.

In a fuller practical sense, the Psychological Contract offers a way to interpret and improve the relationship between employer and employees, with consideration of:

- formal written terms or contract of employment - pay, hours, holidays, conditions, duties and responsibilities, etc

- (potentially any or all) other aspects of the work - job interest, management, development, satisfaction, advancement, etc

- what the employee 'brings to the job' or 'puts into the job' - effort, time, loyalty, innovation, results, etc

- the employing organization's performance and situation - market success, financial strength, or lack of (seen as a sort of 'ability to reward', or 'constraint to reward')

- the state of the job market and economy (for example, alternative job or career options, availability of replacement staff)

And significantly, often overlooked:

- perceptions and assumptions about all of the above factors, which can be very different for employees and employer, and which especially for employees can be influenced by various things, for example workmates, trade unions, media, social networking and other group dynamics and communications - note: perceptions and assumptions of employers can be heavily influenced also - if unhelpfully so this needs addressing

- the employee's self-image - how he/she sees him/herself - in whatever way is significant to the employee

- and, fundamentally influential on the above point and many others - is the employee 'just an employee' or does he/she have a deeper interest in the employer organization in terms of ownership, policies and direction?

We can see the Psychological Contract potentially extending to very deep considerations of the employee/employer relationship, especially in business organizations. This is beyond traditional appreciations of reward and emotional well-being. The Psychological Contract causes us to question the fundamental alignment of employee and employer - specifically in relation to ownership, representational leadership, profit-share, etc - and how this is structured within the constitutional rules and purpose of the organization.

This obviously suggests that the traditional model by which most businesses are run is not necessarily the best organizational structure for achieving a healthy Psychological Contract. The traditional model is probably fine for people who have no interest in their work beyond quite basic inputs and rewards, but it's likely to be an inherently and increasingly strained arrangement for employees who want something deeper, and logically for employers too who seek a deep involvement and commitment from their people.

Traditionally, maintaining a healthy Psychological Contract is addressed by balancing employee inputs and rewards. This exchange typically happens on a constitutional foundation which places employees clearly and firmly outside of the ownership and the strategic leadership of the organization. In many situations, notably 'X-Theory' business corporations, this exclusion encourages and enables real and/or perceived vulnerability, disadvantage, unfairness, etc. The employee may (and generally does) feel disengaged, and not a real 'part of the organization'.

Similar disengagement may be felt by employees of state organizations by virtue of exclusion from decision-making, especially where decisions undermine service quality. Where workers are disempowered at the most basic operating level, the Psychological Contract may need attention at a fundamental constitutional level, i.e., the rules and structure of the organization, which can only be changed by its 'owner' - the state, or other public authority.

Where an organization's basic constitution and rules work against people's core needs, the balancing of employee inputs and rewards almost inevitably becomes a battleground. Serious 'vicious circles' develop, reducing mutual trust and transparency. Crucially, people do not feel aligned with the organization. They work in spite of the organization, not truly for the organization. The wasted potential is considerable.

Self-image is a very significant element in people's assessment of the Psychological Contract. An employee whose self-image is one of a detached remote worker (detached and remote from the ownership and direction of the organization) - a mere 'hired-hand' - will inevitably focus his/her thinking strongly on traditional employment expectations: pay, hours, advancement, job quality, etc., (it's a long list, referenced elsewhere on this page, and see Herzberg's theory for example).

People treated like 'hired-hands' naturally behave like 'hired-hands'.

An obvious question about the Psychological Contract in the modern world is:

If we change the fundamental relationship between the employee and the employer so that the employee is also an owner of the enterprise (or meaningfully empowered, in the case of state organizations), how does this alter the self-image, and consequentially the Psychological Contract?

We would not be changing (hypothetically) the terms and conditions of work. We instead (hypothetically) would change the relationship between the employee and employer at a far more fundamental level. This alters the self-image dramatically. The employee is now far more engaged and aligned with the organization, because he/she has a deep and meaningful interest in it.

Further points about this:

- In many situations a similar deep constitutional change could apply to the relationship between a supplier and its customers.